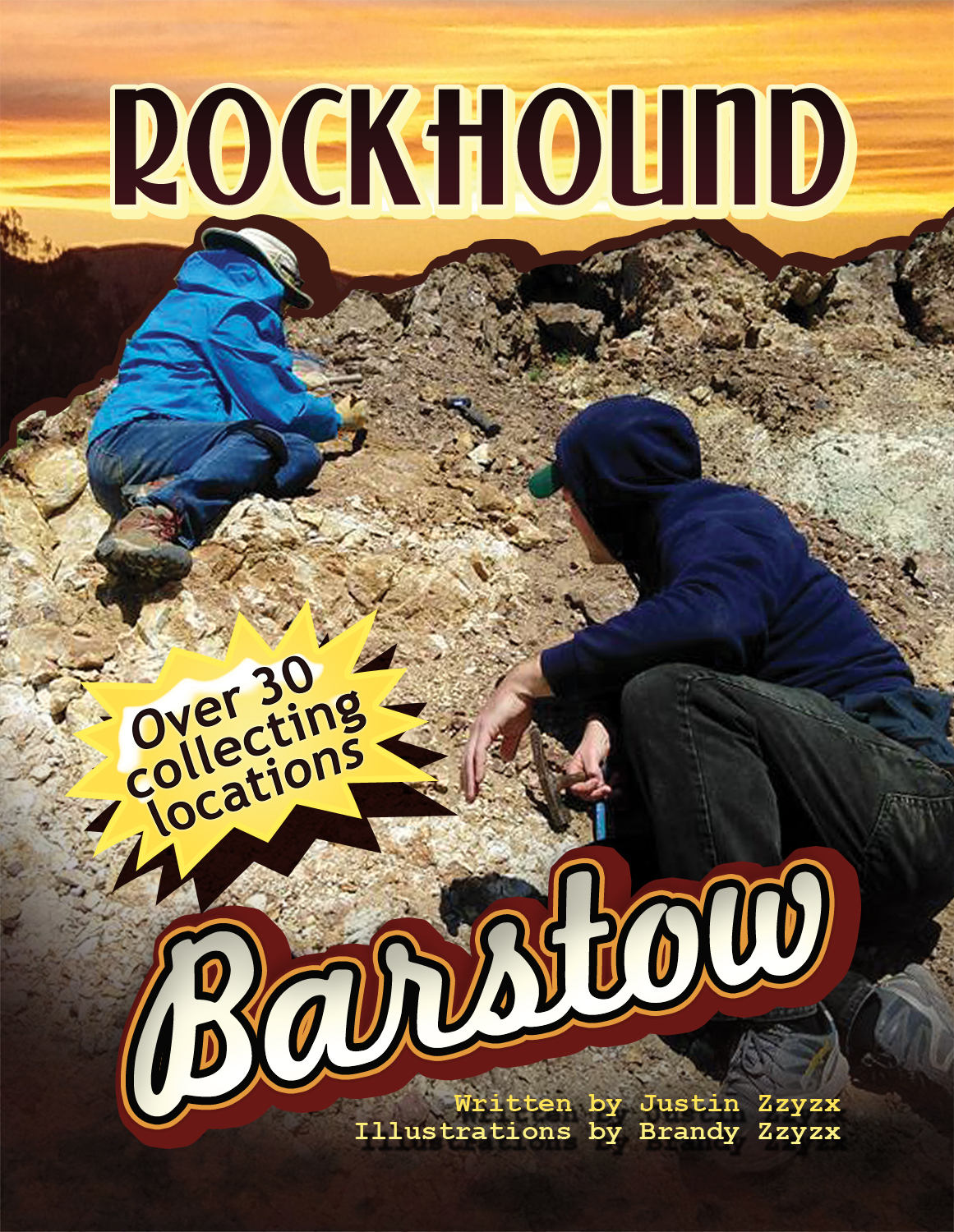

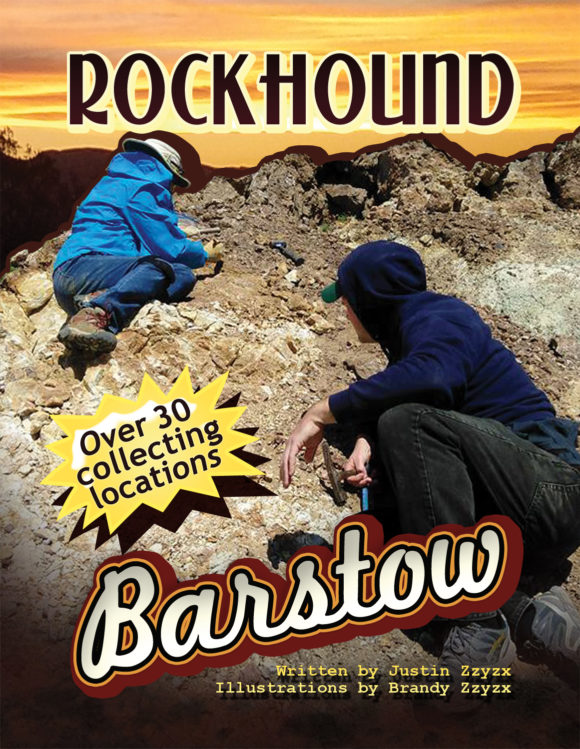

Written by Justin Zzyzx – Author of “Rockhound Barstow”

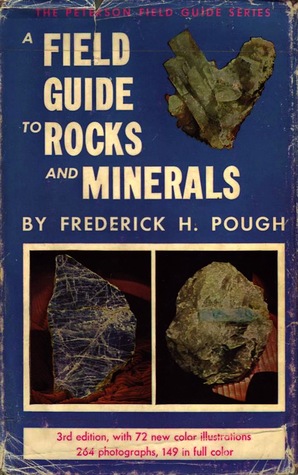

This location and many others are featured in the field guide – Click here to buy a copy for yourself

Click the Cover and Order your copy today!

Justin Zzyzx inspecting boulders at the Noble Prospect.

I just love exploring the nooks and crannies of the hills and mountains around Barstow California. The area around here is known for the beautiful geological formations all around, such as Rainbow Ridge, as well as the silver mines of Calico, once a silver boom town, now a commercial tourist attraction. Barstow, a perfect place to set up base and explore the Cady Mountains, Afton Canyon, Opal Mountain, Mule Canyon, Alvord Mountain, Yermo’s rolling hills of alluvial agates and jaspers and so much more. There is a veritable treasure chest of mineral adventures to be had in these colorful hills, visiting is a thrill, and I, as a resident, love to take full advantages of these rock deposits.

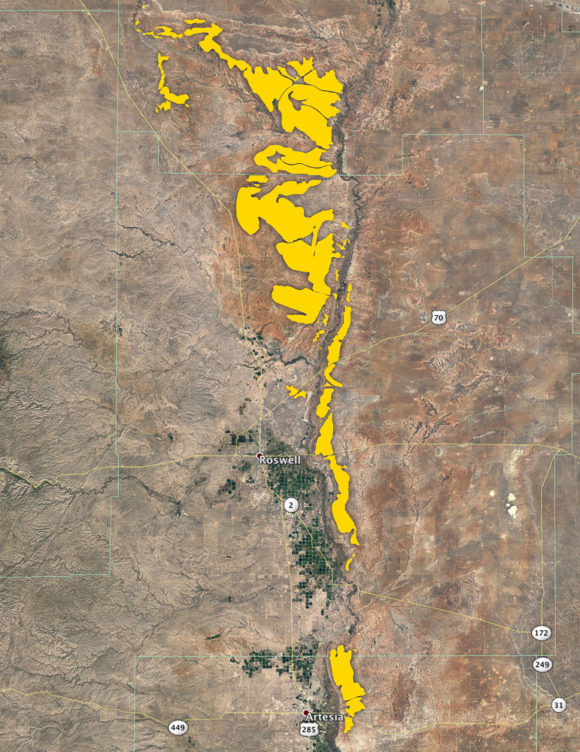

As a frequent leader of field trips and author of the “Rockhound Barstow” field guide, I’m always looking for new places to take people to collect interesting minerals and lapidary materials. My personal favorite is finding places where there are both nice crystallized minerals, as well as colorful lapidary material, that way, out of the dozens of rockhounds who have joined me over the past year on each monthly field trip, everybody is happy with what they can find. Exploring mining information on MRDS.org, I noticed several mines located in the Northern parts of the Calico mountains. I could see, just 10 miles away from my pistachio grove I call home in Newberry Springs, there was a Wollastonite mine, a Nickel mine and an Arsenic mine, all bunched up to the West of Coyote Dry Lake.

View looking out to Coyote Dry Lake from the un-named Nickel deposit

On our first outing to this string of locations we tried to access it from the East, coming up Coyote Dry Lake road. The dry lake was not as dry as we expected, in fact, it was quite moist and with no desire to go “muddin”, we turned back and tried the other way into the area, all the way around the Fort Irwin road passage, 20 miles to the West. Fort Irwin road is a VERY busy two-three lane road that connects Fort Irwin to Barstow and highway 15. Fort Irwin, a large Marine base, requires a large amount of workers from the Barstow area to work the service industry jobs, as well as the tech jobs, along with all the contractors, you can imagine this is a very busy road. We drove through the pass on the West side, looking at all the remains from the silver mines that made the Calico district what it was and what it is today. The ore was mostly chloragyrite, a silver mineral that is toxic to process, proving to be costly and environmentally unsound, so, the silver mines stand dormant, forever.

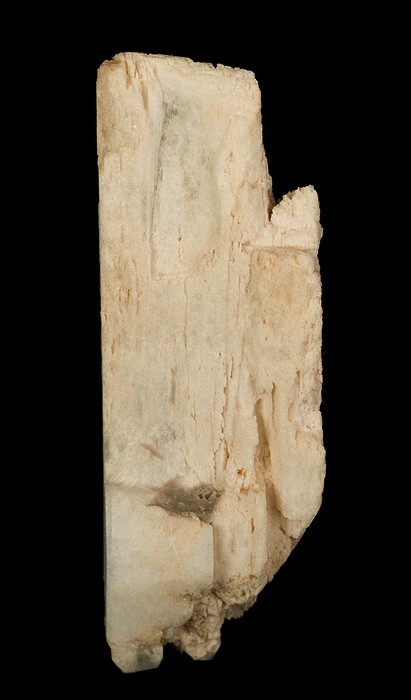

Entering on Madrugador road, Eastbound from Fort Irwin road, you pass by a Wollastonite deposit to the North, which we inspected with little of interest to be found, then, continuing along on this fairly smooth, slightly rocky road we turned off to the Northeast on a power line road which then takes us directly to the Wolly Wollastonite #5 deposit, a long abandoned deposit of this interesting white mineral. Some field guides have published this location, however, they always refer to it as an Onyx deposit. Onyx, a name for Calcite, is found at lots of places around the Calico mountains, however, at this deposit, there is only the non-stop white bliss of massive Wollastonite.

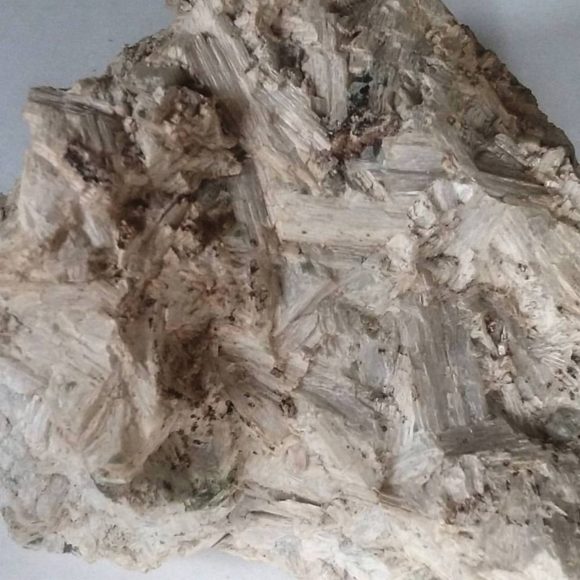

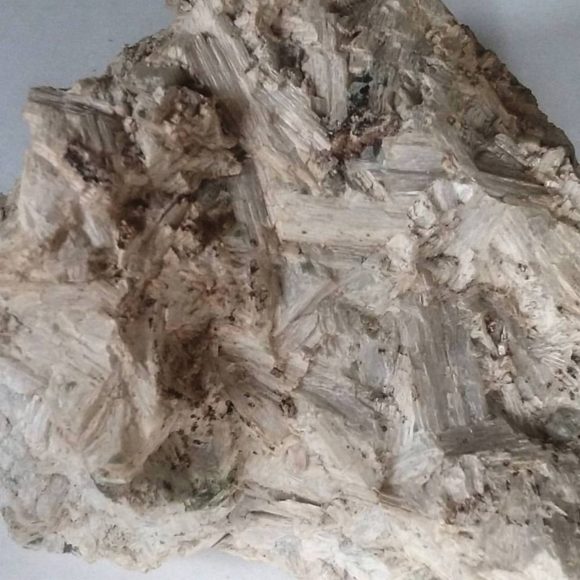

Long fiber Wollastonite crystals on the surface of massive Wollastonite

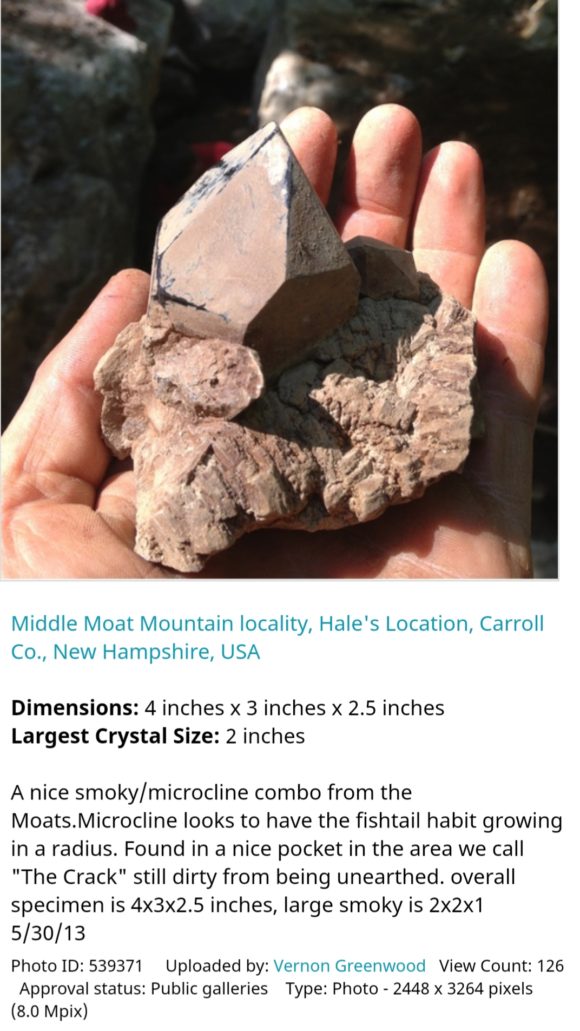

Wollastonite is a mineral that can be found as part of a Skarn deposit. Common related minerals are Grossular Garnet, Calcite, Quartz, Hedenburgite, and Epidote. The grains of the skarn deposits can be quite dense, leading to amazingly hard stones that can be worked into lapidary objects like vases and pillars. The wollastonite here was most likely mined for use in the pottery industry. Wollastonite, CaSiO3, a Calcium Silica Oxygen mineral that often has impurities of iron, manganese and magnesium, all elements found in abundance across this mountain range. Crushed, this powdered rock would be used for adding to clay, reducing cracking when ceramics are fired in a kiln, as well as added to paint base, a filler to make paint thicker.

At the Wolly Wollastonite deposit we would find tons of massive white wollastonite with the choice mineral specimens being the small bits and thin plates of acicular “long fiber” wollastonite crystals, which form flat on the surface of the rocks and boulders. Along with these, a bit of orange Grossular garnet can be found forming in the sharp borders between the wollastonite and the county rock. Finding larger pieces of this material is uncommon, but possible, however bits of wollastonite with thin areas of garnet are fairly common along the waste rock piles. In the quarried areas, along the rock wall, you can see several veins of garnet, but, in my opinion, they are not terribly thrilling. One thing is for sure, the guides that have continuously pegged this as an Onyx deposit can now be corrected in the next printing! The deposit takes up the Northern side of this far outlying mountain, spilling out of the most Northern part of the Calico mountains. Various bits and smears of other minerals have been spotted, like epidote and hedenburgite, so with further exploration you might uncover something interesting.

Spessartine garnet masses found in conjunction with the wollastonite deposits of the North Calico Mountains

A few months before I decided to visit this Wollastonite deposit, I was told by a gold miner in the Hesperia area that there was a Wollastonite deposit up in the North Calico mountains that had terminated grossular garnets. Wollastonite forms as a part of skarn deposits. One of the best mineral deposits in these formations are calcite pods with glossy grossular garnets underneath. Locations around the world produce specimens like this, the calcite acts as a blanket for the garnets, protecting them from any harm, until we, rockhounds, remove them from the ground and soak them in acid to dissolve the calcite and reveal the beautiful garnets underneath. While massive garnet is found at the Wolly Wollastonite deposit, the lack of calcite pods at this and every other Wollastonite deposit I’ve visited has turned up fruitless. Yet, chasing this lead has brought me to explore some infrequently visited areas of the rocky desert hillsides.

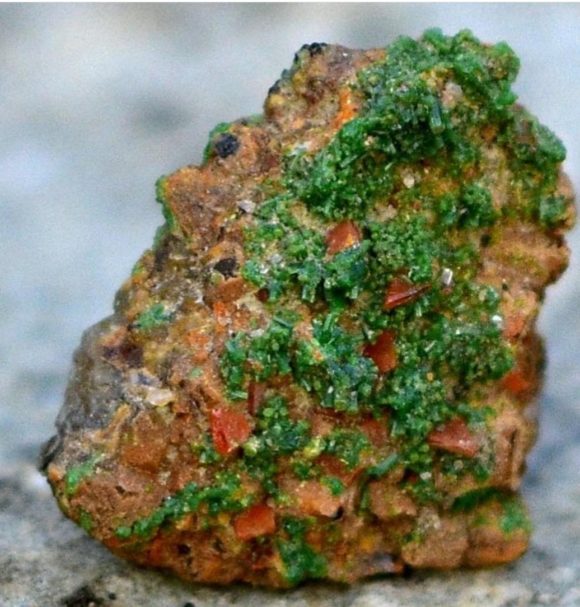

Going back in reverse from the Wollastonite deposit, you can head South in the first turn, which is a wash that leads up to the solid hillside and upwards on a road that leads to a former Nickel deposit, resting on this craggy spire, a semi steep climb leads to a non-connecting circular road around the peak. From here you have spectacular views of the valley below, the vast white/tan of Coyote Dry Lake, the Coptic monistary, and hey, I can even see my house from up here! Looking at this location from the comfort of my home, with my imported mine marker data from MRDS, I could see this Nickel mine and also find out more information about it. It referenced a mention in a a Southern Pacific Railroad booklet on Mineral of Industry, Volume 3, which mentions the deposit geology as “niccolite, arsenopyrite, annabergite, and uvarovite in a verticle silicic dike that strikes NE along a shear zone in hornfels and quartzite.”

View from on top of un-named Nickel deposit

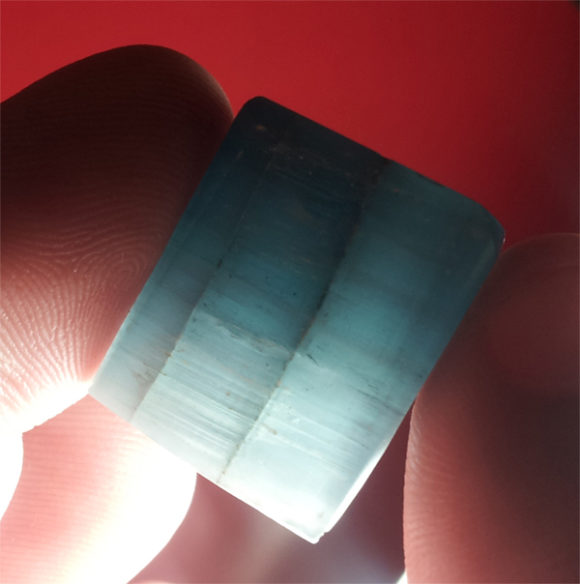

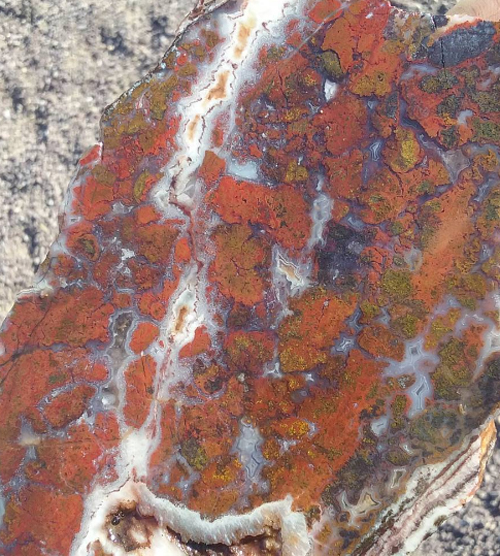

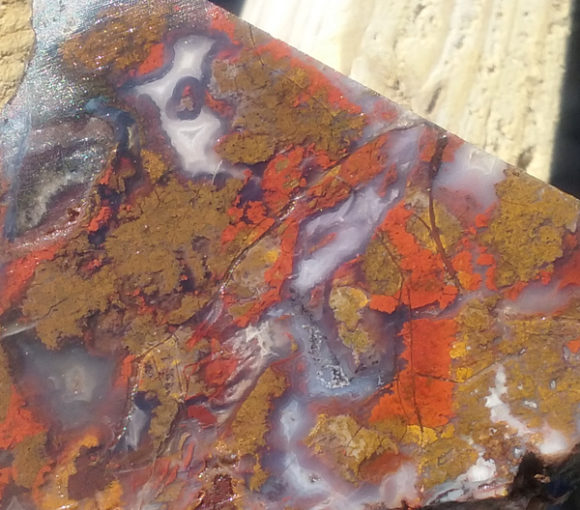

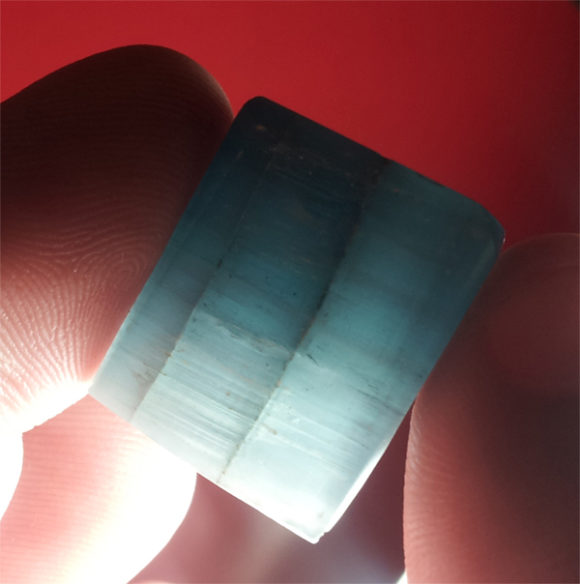

Off we went, to go visit the un-named nickel deposit. The wind on our first visit makes the location very memorable. We can have wind gusts over 65 miles an hour on some days around these parts and that day the wind was so forceful we were quite worried we would be swept off the mountain. Maintaining a tight foothold, we explored the area, looking for bright green crystals of annabergite and chrome green uvarovite garnets. Instead, we found the meaning of “silicic dike”! All of the minerals we have found at this location have been frozen in blocks of silica. While this does not do anything for us mineral collectors, it makes for a unique lapidary material. The same stuff as the classic German “Nickel Quartz”, this green stone takes a nice polish and the contrast of white and green makes for an interesting stone. Floating around in this silica, tiny bits of chrome green uvarovite garnet are found, while nothing to write home about, they do add a little something to some of the slabs and tumbled stones we produced out of this ore. If there were crystals here, this could be one of my favorite locations, but even in massive lapidary form, this in a rare treat in terms of mineralogy, a geat view-point in this area of the North Calico mountains and yet, just one of many locations in a short distance in this mountain range.

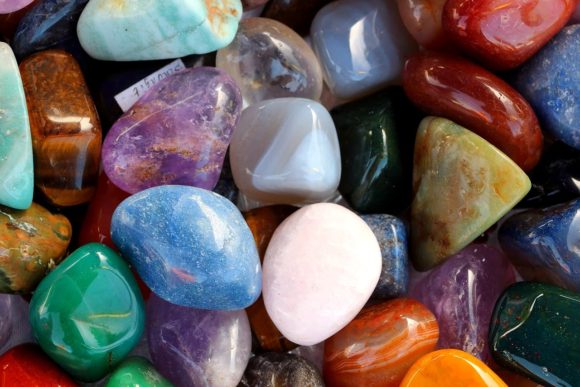

Tumbled nickel quartz from the un-named Nickel deposit

Just off to the Southwest, the road takes you to the Puerto Negro mine, a series of rock dumps that stop at a mine entrance a few hundred yards south of the beginning of the dumps. This is an Arsenic mine that produced an arsenic rich ore with the occasional bit of calcite and realgar. While I have not found many specimens at this location, the few I have found have been quite uncommon, orangy red realgar in layered clear calcite crystals. Drive North to connect back with the power line road and drive over to the next canyon to the South, taking Madrugador Road, home to several prospects for copper and gold, before heading back out to Fort Irwin Road. These gold deposits do not have much in the way of collectables for mineral or lapidary enthusiasts, however, they do produce chunks of calcite and masses of red, iron stained, quartz.

Entrance to the Arsenic Mine, the Puerto Negro

From here, it is time to go across Ft. Irwin Road, just a few hundred yards to the South, a road stretches out towards the Northwest, reaching out to several locations were crystals and lapidary materials can be found. The road is a very nice, mostly smooth flat desert dirt road. There are a couple tiny washed out areas, but most any passenger car can navigate the area. Immediately to the North, a small set of ridges spread out, the ridge to the West of the hills contains two locations to explore. A massive Barite locality called the Ball mine and a funky Wollastonite deposit with some odd rocks to be found. You pull off this new dirt road and into a wash road that loops around, park here and hike into the mountain valley to find the Ball mine, which is easy to see and high up on the hillside.

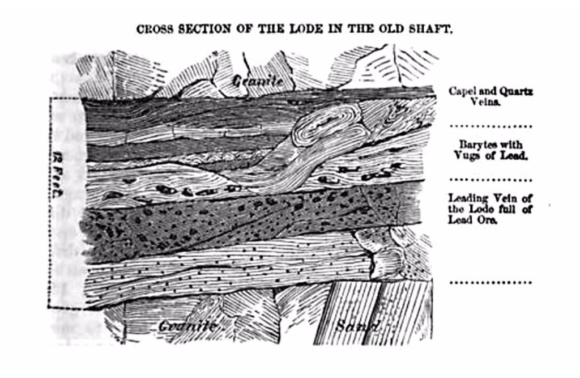

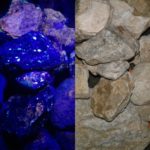

The Ball mine was a series of tunnels and surface workings that produced massive white barite, which can be found in abundance as lumps of heavy white rock. While unassuming, when exposed to UV light, these lumps glow a pleasing green and pink. There are tons and tons of this material laying around the mine adits, so you will have plenty to choose from. Continuing North into the canyon you will come across a Wollastonite deposit that has bits of calcite and some black rock that is said to be chromium bearing.

Rockhounds collecting Garnets at the Nobel Prospect

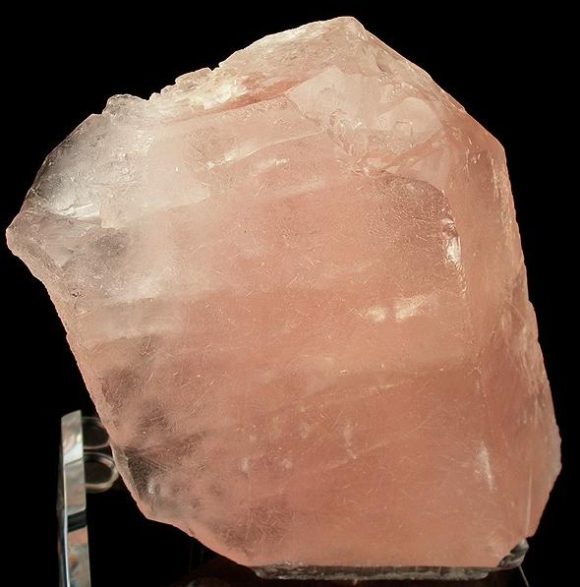

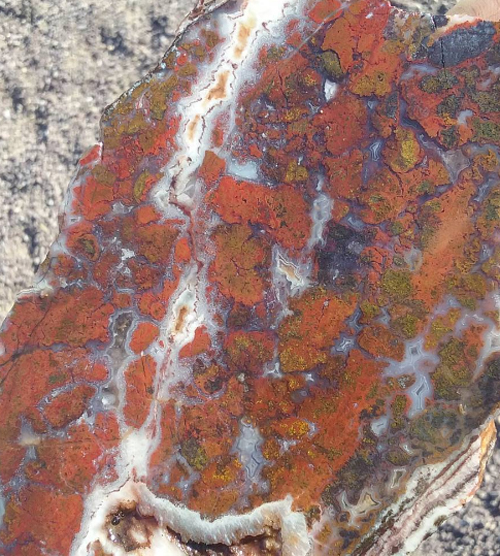

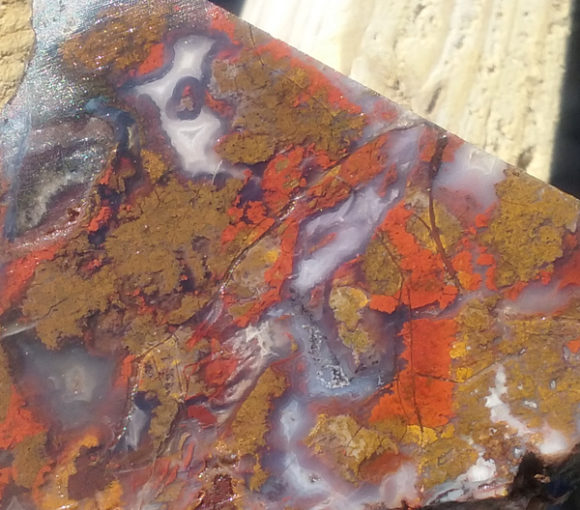

Back on the main dirt road, you continue Northwest for a mile or so until you come across a faint road headed South which leads to a large pile of rocks in the middle of the flat desert. It is unusual to see a pile of rocks such as this, however, this outcropping of rock is a happy accident for all of us. Here you can find a great deposit of Onyx, a flowing series of banded tans and yellows, along with bright red caused by iron impurities, along with areas of quartz, in the center of the stones as well as on the surface. Druzy specimens of quartz and calcite can be found, the only drawback is the size of the matrix they are sometimes attached to! The large chunks of stone cut to reveal beautiful patterns, while being nice and crack free, solid cutting material. It is remarkably easy to find, within a half hour at the location, cutting material to keep you occupied for days and weeks.

Sliced Travertine from the large travertine outcrop in the North Calico Mountains

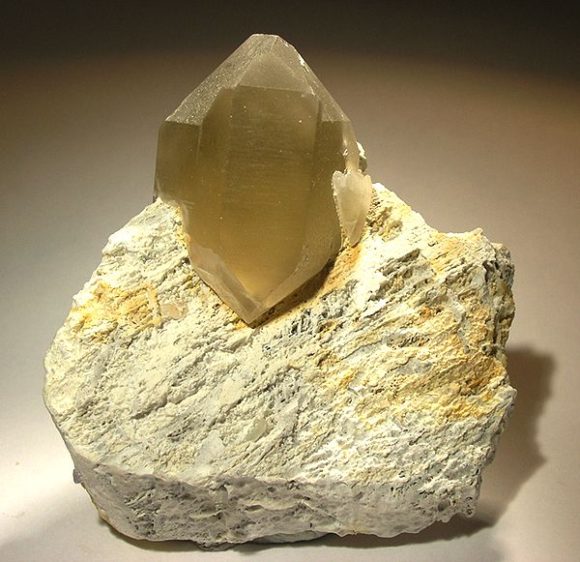

Traveling only another thousand yards to the West along the main dirt road, you come across the Noble prospect, a mineralized zone consisting of a short canyon wash to the East, with short adits that pushed out garnets, quartz, epidote and calcite. While we were hoping for garnets trapped inside calcite pods, these garnets are frozen in a quartz matrix, an while crystals can get up to an inch across in size, there is no way to free them from the host rock. Still, terminated garnets can be found in this area and the masses of quartz, epidote and garnet make for interesting lapidary materials. Just a short distance from this wash, a road takes you a few hundred feet to a bench in the mountainside, filled with boulders containing calcite crystals and quartz druzy, the druzy areas measuring up to and over one foot in size on several of the boulders. The trick is to find specimens that are small enough to take home. Several pieces showed evidence of layers of quartz covering and replacing the calcite crystals, which make for very interesting mineral specimens.

At the Noble Prospect, Boulders of Calcite with Crystals growing in vugs can be found.

Calcite crystals plucked from the walls of the Noble Propsect.

If you like this article, check out the 28 page full color field guide “Rockhound Barstow” for sale online at the following links

Buy it on eBay

Order it on Amazon, or Buy it for Kindle eBook Readers

Or, hey, here is the map…

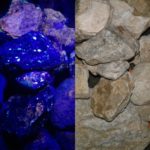

I enjoy seeing rocks light up under Short Wave Ultra Violet light, so do millions of other people in the world. It is exciting to see brilliant colors coming from, what commonly is, a not very visually stunning rock. While large exotic crystals can fluoresce, many times it is something drab and visually unappealing that shows brilliant reaction to “black light”. As the field trip leader for an active group of rock hounds, my monthly trip for February of 2017 was to the area known for brightly fluorescent rocks in the Shadow Mountains, just West of highway 395, in the high desert of Southern California.  Every month we lead a field trip for the Mining Supplies and Rock Shop in Hesperia California, visit the shop and join us!  This photo shows the typical rocks found at the Shadow Mountain Tungsten District under normal light and under SW UV light. To start out my planning for this trip, I did a basic Google search for what I thought the name of the mine was, the “Princess Pat Mine”. Google brought up some pages with various bits of information, some photographs, but no real indication of where the mine was specifically located. I then turned my attention to MRDS, as talked about in Rockhounding 101, this site can give me a list of mines, pinpointed on a map, showing what has been found in the area. It was a surprise to see that while there were a dozen or more deposits for Scheelite, the highly UV reactive mineral we were after, none of the mines were called “Princess Pat”. However, looking at the Google map, I noticed the road that takes you right to the majority of the scheelite deposits was called “Princess Pat Mine Road”. In fact, you simply turn west off the 395 onto this unmarked road and go for 5 miles until you hit the collecting area. But, why was I having such a pain finding the “Princess Pat Mine”?

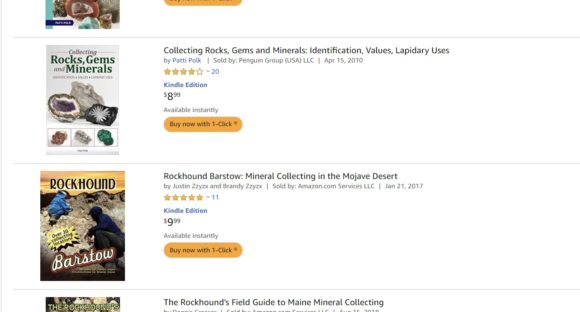

I broke open Pemberton’s “Minerals of California” to find an entry for the Shadow Mountain Tungsten deposits on page 337, where it states “6. In the Shadow Mountains, on the northwest flank of Silver Peak, there are a number of scheelite deposits consolidated as the Just Associates quarries. The scheelite occurs in quartz veins cutting garnet-epidote-quartz tactite.” – however, no mention of the “Princess Pat Mine” – So, could it have been that the name “Princess Pat” was older or newer than this 1983 tome of California minerals? With this, I pulled out the Murdoch and Webb version of “Minerals of California”, 1966 edition, which leaves out the Shadow Mountain tungsten mines from the entries on scheelite in San Bernardino County.

Luck would serve me up a reference to “California journal of mines and geology”, Volume 49, which featured a fantastically in depth article on ore bodies of San Bernardino County, which reads

Just Tungsten Quarries (Just Associates, Princess Pat, Shadow Mountains Mines). Location: sees. 30 and 31, T. 8 N., R. 6 W., S.B.M., on

the northwest flank of Silver Peak, Shadow Mountains, about 13 airline miles west of Helendale and 14 airline miles northwest of Adelanto.

Ownership : Just Associates, E. Richard Just and Oliver P. Adams, 726

Story Building, Los Angeles, California, own unpatented claims totaling 440 acres. The property is leased to Just Tungsten Quarries, E.

Richard Just and associates, 726 Story Building, Los Angeles, California.

The deposit, now known as the Just Tungsten Quarries, was discovered in 1937. Operations from late 1937 to early 1938 by the Shadow

Mountains Tungsten Mines and W. A. Trout and C. A. Rasmussen re-

sulted in the recovery of about 750 units of W0 3 from nearly 3000 tons

of selected ore treated in a 40-ton mill on the property. The operation

was not successful and the mill was dismantled. During the mid-1940 ‘s

lessees mined about 400 tons of ore, and during the late 1940 ‘s the

Princess Pat Mining Company leased the property but apparently produced no ore. Operations from April 1952 to mid-1952 have yielded a

few hundred tons of ore of undisclosed grade.

The scheelite occurs in quartz veins cutting garnet-epidote-quartz

tactite bodies which exist at the contact between a Mesozoic granitic

rock and Paleozoic ( ?) metamorphic rocks, mostly impure limestone and

schist. The foliated rocks strike slightly north of east and dip gently

south. Scheelite-bearing tactite also has been developed, away from the

contact, along beds in the limestone, to form thin bodies of ore separated by barren limestone beds.

The deposit was explored during 1937-38 by 1800 feet of zig-zag

trenches, 10 feet wide and 6 to 10 feet deep, excavated by a power shovel

up a moderate slope in a southwesterly direction. A 65-foot vertical shaft

was sunk near the lower end of this trench system, but no mining was

done underground.

Employed in the early prospecting was a large field-type lamp requiring a 110-volt current, and a portable gasoline-powered motor generator set. This may have been the first practical application of a lamp

of this type.

Ore is being mined from a bench cutting into a trenched area about

50 feet north of the shaft. Mining operations are carried on at night,

and the ore is sorted with the aid of ultra-violet light. Shipments have

been made to both the Jaylite and Parker custom mills in Barstow.

There you go, the “Princess Pat Mine” has the distinction of being a mine that produced no ore.

As it was, the tungsten mines produced little more than some naming confusions and quite possibly some bad debt, as the scheelite riches would never quite materialize from this deposit. Tungsten is an element that was listed by the United States Government as a strategic reserve, as most of our Tungsten comes from China, during WWII it was known that it would be scarce, so efforts were made to ensure production could be met at home. Plenty of trenches and tunnels were driven in this 140 acre unpatented claim, in the end, producing nothing more than a playground for collectors with an UV light.

The mostly smooth desert road is littered with rocks that glow under SW UV light There is often a little confusion as to what kind of Ultra-violet light one needs to get the enjoyment out of collecting UV minerals. I have used many varieties of products and I’ve found what I like and what I do not like. Obviously, a light with ample power is what one wants. Small hand held units are commonly available in 6 watt and under, which gives you a reaction when you hold the light VERY close to the specimen. However, the difference between a low wattage light and something in the 9, 18, or even, 36 watts will astonish every viewer. If you want maximum enjoyment out of UV collecting, a dual wave 18 watt light is a sound investment. Some minerals glow under Long Wave (365nm) range, but honestly, I find Long Wave to be the most limited, while Short Wave (285nm), produces amazing effects. When it comes to companies, well, some come and some go, while some are longstanding companies that I do not personally enjoy, when it comes to price vs. what you get, so, I would like to steer you in the right direction. At this time, in winter of 2017, there are no good companies to purchase a UV light from on Amazon.com. In fact, I would push you in two directions. #1, UVTools.com – They have been producing some fine lights, which come accompanied by a great informative kit. I highly recommend all the units they sell, even the sub-9 watt lights. #2, on eBay, the seller topazminer_minerals_and_fossils has been having great deals on a fine selection of high powered lights, at very reasonable prices. I would suggest viewing their offerings when looking for a great UV light.

|

If you like this article, check out the 28 page full color field guide “Rockhound Barstow” for sale online at the following links, now including the Princess Pat Mine Area, indepth!

Buy it on eBay

Order it on Amazon, or Buy it for Kindle eBook Readers

As part of the field trip series that I lead for the Mining Supplies and Rock Shop in Hesperia California, we took a trip out to the “Princess Pat Mine” area, or, as it should be known, the Just Associates Tungsten area, or, even still, the Shadow Mountain Tungsten area. You simply follow Princess Pat Mine road from highway 395 for 5 miles and you will find yourself facing the various prospect pits and trenches filled with cobbles and boulders of mostly white rocks that will glow readily under short wave light. You will see bright orange from the potassium rich calcite caliche, you’ll see bright green from the uranium included quartz. The bright white/blue scheelite is the real winner, appearing as belts of star-like dots in the rocky background. Rarely, one can find bright red from the wollastonite found in the area.

We have lead field trips for various groups and organizations  This pile of ore rubble was waiting for us at the parking area 1/10th of a mile from the start of the major trenching. This pile of rocks glows brightly if you do not wish to go into the rocky tailings beyond. A group of about 30 of us descended on the mine area around 5pm, getting a view of the area before the sun set, by 6pm we were ready to see some rocks glow! Many of us came equipped with various powered UV lights. Some of the inexpensive LED Longwave lights were causing the calcite to glow a slight pinkish, but that was all, while the Shortwave lights were causing the whole area to light up. Everything around the area was glowing light wild, which lead to lots of happy rockhounds and many people remarking that they could not wait to come back and bring friends to show this wonderful area to. In this lonely desert, with no lights besides the moon and the stars, one can get some amazing results with a short wave ultra-violet light!

There were plenty of trenches pushed into the mountain which make great areas to illuminate the walls in search of black light rocks  In the dark, scanning for rocks that react to SW Ultra Violet Light is a blast!  Here is a rock responding to SW UV light on the mine dump at the Princess Pat Mine/Just Associates Mine So, go out and enjoy a day or night at the Shadow Mountain Tungsten District. There are no active claims, there is no ore of worth, it is just you and the coyotes, howling at the moon and looking down at the twinkling scheelite stars…

Check out the new expanded Rockhound Barstow, in full color and larger size! UPDATED 3rd Edition Released August 2020 – Get it now direct on a PayPal link, or check it out on Amazon, eBay and Etsy

The Mojave desert is a mineralogically rich area. One small town of less than 30,000 people serves as a great jumping off point for dozens of fantastic collecting sites. Many of these locations are Southern California classics, found in field guides dating to the early 1940’s and surprisingly, still producing to this day. The Cady Mountains are an endless source of material. You can be sure that enough time spent in the loving folds of the Cady mountains will reveal some mind blowing treasures to the lapidarist.

Top Notch Agate being cut into slabs. The Cady Mountains produce beautiful treasures you’ll love working with!  A sampling of cabochons made from material found in the Cady and Alvord Mountains Just a few miles outside of Barstow you hit the Calico Mountains with a vast silver district, an amazing series of borate deposits, celestite for days, tons and tons of fine selenite and ample supplies of petrified palm root just pouring out of the hills…and silver lace onyx and calcite concretions that can have celestite and quartz replaced spiders and flies inside! That is just the things you can find in a small mountain range just four miles north of highway 15!

Polished Celestite from one of the many celestite deposits found along with the Borates of the Calico Mountains  Gem crystal clusters of Colemanite are found in the Calico Mountains, ready to come home with you!  Colemanite glows bright in Short Wave Ultra Violet Light, like MANY of the minerals found in the area. One of the reasons Barstow is such a great starting point for rockhounding in this area is the prime location. Just 2 hours north-east of Los Angeles and 2 hours south-west of Las Vegas, this town has most everything you need for traveling in this area. Gas, groceries, hotels, restaurants, even the Diamond Pacific Rock Shop, attached to the Diamond Pacific Lapidary Equipment factory. Emergency services, like tire and vehicle repair can be found in Barstow so that even in the worst of conditions, there is somewhere “local” to take care of any problems. Convenience is what Barstow provides and there is no reason why that is not a good thing!

|

Buy it on eBay

Order it on Amazon, or Buy it for Kindle eBook Readers

Who better to write and produce this Barstow rockhound field guide than the field trip leaders, Justin and Brandy Zzyzx – locals to the area and avid rockhounds, each of the locations in Rockhounding Barstow have been visited by Justin and Brandy. Justin wrote the text and Brandy designed the maps, as you can see in the sample below.

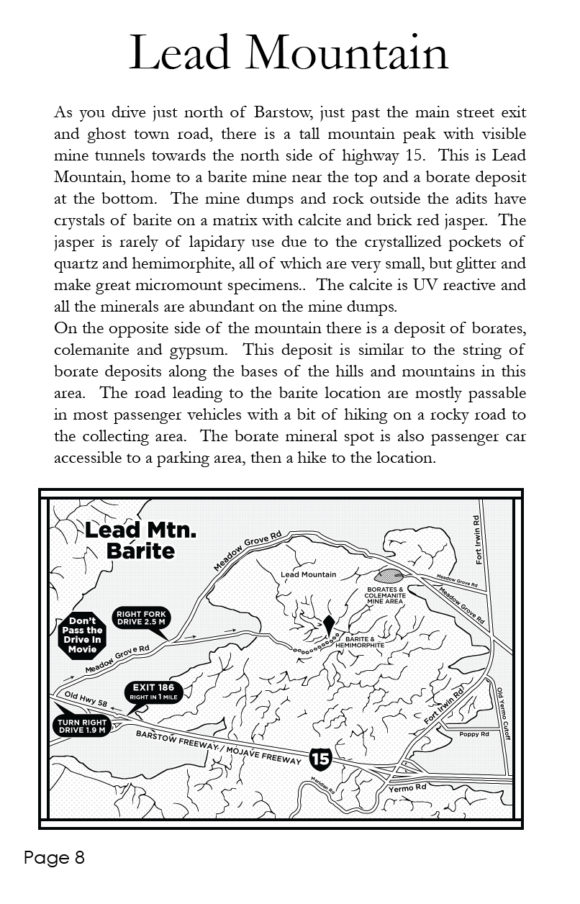

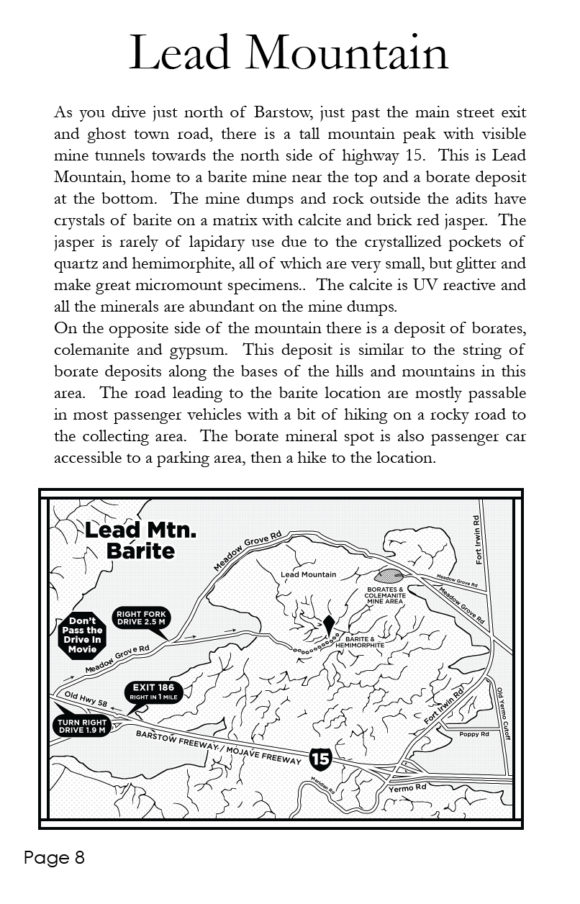

Sample page from the Rockhound Barstow Field Guide – Lead Mountain, just a couple miles from highway 15, a great place to visit and collect colorful crystals! Many of the locations have been written about before, while some of them are being published in this field guide for the very first time. One of the locations that is very exciting is the North Cady Mountain collecting, including the Top Notch claim, prospected by Bill Depue and John Pickett, of Diamond Pacific. This spot has been producing some really lovely material, bright red, golden siderite, fortification and banding of clear and lavender agate. Oh, a day collecting here just can not be beat! You are going to get directions to this very spot and over 30 more locations, just waiting for you to come visit.

Bright Red and Golden Top Notch Agate from the North Cady Mountains, featured in the Rockhound Barstow Field Guide  Siderite is not a common inclusion in agates so it is a welcome site to see this material, rich with gold and red along with beautiful gel agate from the North Cady Mountains Another interesting feature is the interactive rockhound map provided in the guide. Simply type in the website address and on your phone google maps will open up and you’ll be provided with a pinpointed map featuring all the locations in the book PLUS additional locations, each of them showing you EXACTLY where to collect. Most of the locations in the books will have cell phone service, allowing you to use the interactive google map as a guided satellite directly to the collecting location. Truly a first in terms of mineral collecting field guides!

This fun “Nickel Quartz” comes from the North Calico Mountains Nickel Quartz, Wollastonite, Garnet, and so much more await you, with new locations added occasionally. By now I’m sure you are chomping at the bit to find out how to get your copy of this booklet. This digest sized field guide, with a color cover, color photographs of what you can expect to find, over 20 collecting locations, all this can be yours for $14.99 plus shipping and handling! That’s right, just $14.99 plus shipping gets you a fountain of information, right at your fingertips!

Simply use PayPal to order directly by Credit Card or your PayPal account or purchase a copy from Amazon, Etsy or eBay.

The abundant Gypsum/Selenite in the Calico Mountains is great for tumbling, polishing, carving and collecting. We use it as a water softener.  The Lavic Sidling Jasper location is not just limited to the classic areas, but also spilling out to the West and North of Pisgah Crater, as you’ll see in the Rockhounding Barstow Booklet  Chalcedony Roses are very abundant out in the Mojave Desert

The noon sun hung in the sky with a dull yet irritating heat. It was early Spring, and I was traveling to a place nobody had any reason to be, an empty valley in Central Utah. I grabbed the canteen swaying from my hip, took a hearty swig, and wiped the small beads of sweat slowly forming on my brow. The dry earth crunched with each trod of my heel, one after another like a rhythmic drum, each thud forming a slow monotonous beat.

I took in my surroundings. At surface level there was not much to see, canyon walls and plateaus, little wildlife, and less trees. What little vegetation was found here often amounted to sagebrush. It peppered the dirt in various shades of chartreuse, flowing lightly with the siblant hissing of the wind. I was two miles south of Marysvale, Utah, a small town with less than five hundred residents. On this particular expedition, I was alone.

The area I was headed to was the now abandoned Elbow Ranch. On my shoulders slung a backpack stuffed lightly with supplies: a fold up shovel, a pair of gloves, a chisel, a spray bottle of water, a rag, the morning newspaper, a loupe, and a geologists hammer. I also made sure to leave some empty space for any of the various specimens I hoped to collect.

I’d spent the earlier half of the day in the Durkee Creek area. Durkee Creek was much easier to reach than the hike to Dry Canyon had to offer. Most Rockhounds with already impressive collections probably wouldn’t have bothered spending the time there. The red-brown earth of Durkee Creek offered an abundance of zeolite, but they were often small specimens that didn’t equivocate to the effort involved.

It wasn’t until one o’clock that I found an area that had seemingly been untouched. I unfolded the shovel, wedged it between the cracked earth, and began digging. With each downward stroke I hope for the sound of metal scraping rock. It was four feet down where I found it: mordenite, an orangeish pink rock like rusted iron. With my chisel and rock hammer I chipped at the rock, a tedious process requiring delicate precision. When I’ve made enough of the outline I wedge the pick in and remove the specimen like a loose brick.

A quick spray from the bottle and a wipe of the rag gave the rock a quick polish. The mordenite was about half a centimeter thick, forming a crust for the interior of crystalized white quartz. I held it over head where the light could reach, twisting it in hand, watching it blink and shimmer in the afternoon sun. I recall thinking a familiar thought, an image of this same area long ago. A memory strung together from vague recollections of scientific studies and my own personal imagination. It was a hostile world, fiery and volcanic, but one small pocket of that world had been preserved. A fracture of time lying dormat, imprisoned and pressurized for thousands of years, found by me after a series of seemingly coincidental happenstances.

I tore a page from the classified section of the day’s paper and wrapped the mordenite with care, then I climbed my way out of the hole. The sun stood due west, glaring. My wrist watch read 4:00 pm. In Marysvale Utah many of the residents are returning from work, preparing for dinner and the days end. I grab the canteen, and wipe my brow. Then I gather my gear and continue on. I’ve yet to try my luck at the Blackbird Mine.

|

Gem Trails

by Various Authors

The Must Have, if nothing else than to have an IDEA about the collecting spots in your state, the gem trails books are a wealth of information at a low price. The perfect beginner guides that are refrenced by serious field collectors! Click on the book covers to view them on Amazon, or search the eBay link below.

Gem Trails on eBay

How to prepare your 4×4 for rock collecting.

Rock collecting may be a popular, family oriented activity, but how often do you think of the safety of your family first when you go off the beaten track to hunt for that one, perfect example of a billion-year-old rock? How often have you heard of people being stranded without food and water for days, just because the driver did not check his vehicle before leaving home? Don’t let this happen to you and yours! Simply follow the few easy-to-follow tips listed here to reduce the possibility of vehicle breakdowns when you could be hundreds of miles away from the nearest repair shop.

Check radiator hoses.

This might appear to be self evident, but according to the AAA, engine overheating is the leading cause of vehicle breakdowns in America. Radiator hoses must be firm to the touch, and free of oil, and even oil residue. Oil degrades the rubber of radiator hoses, which makes it imperative that oil contaminated hoses be replaced before your next trip.

Check all V-, and other drive belts.

You may think your belts are OK, but the most damage occurs when the pieces of a broken drive belt work themselves in under the other drive belts. This can cause all your belts to jump their pulleys, and because of their high rotational speed, the flying pieces can destroy the radiator, the battery, the radiator fan, and critically important wiring. When in doubt, don’t procrastinate, replace all the belts, and observe the proper tensions on all.

Check the charge rate.

The proper rate of charge on 12 V vehicles is 14.2 – 14.6 Volt. Anything above or below this value is indicative of a faulty alternator, or maybe worse, damage to wiring in places where you cannot repair it in the wilderness, so fix it now, while you can.

Check battery condition.

Don’t just look at the outside, and maybe clean off acid accumulations. A battery needs to be able to deliver specific currents at certain times, such as during starting. Have an authorized battery dealer perform a draw test, to determine the ability of the battery to deliver sufficient starting current. Also, compare the specific gravity of the electrolyte in each cell against the specs for your battery. Differences of one or two percent are normal, but differences or deviations that approach 5% are not, and you should replace the battery.

You don’t even want to THINK about how much it costs to get a jump start in the desert, 80 miles from nowhere. Check the suspension.

Check the suspension and steering systems for excessive free play between related components such as ball joints, tie rod ends, steering dampers, draglinks and control arms. You may think that since the tie rod ends have been a little loose for the last two years, they are OK because they have not pulled from their sockets yet, but off-road driving places extreme loads on a vehicle, and the last thing you want to happen is to lose your steering while going down a steep, rocky hillside. Think of your family, and replace all worn components before you leave home.

Check the brake system.

Check the entire system for signs of leaks, and do NOT forget to check the slave cylinders inside the brake drums. These cylinders can lose up to 60% of their effectiveness before they even start to show signs of leaking, which means you could be driving around with less than 50% of your braking capacity. Moreover, if you had been topping the brake fluid reservoir regularly, but cannot see a leak, remove the master cylinder from the brake booster to check if the brake fluid is not leaking into the booster. If this is the case, replace the entire master cylinder because you can never be sure the rubber seal kits available today will not fail you when you need them most; such as when you are going down a steep, very narrow mountain pass, with a 1000-foot drop off, and no safety barrier.

Better safe than sorry.

Performing basic vehicle maintenance procedures before heading into the wilderness is not a hassle: it is a vital precaution against being marooned hundreds of miles from the nearest repair facilities. It is also great way to prevent potentially fatal accidents caused by parts that failed because they should have been replaced months ago, but was not. Think of the safety of your family, if not your own, get your vehicle into great shape, and enjoy the rock hunting, which is what you go into the wilderness for, right? Only make sure that by taking care of your vehicle, you can safely make it out again!

Field Trip: Copper Country Collecting in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula

By Jeremy Zolan

Difficulty Level: Easy to Moderate

Supplies Needed:

Safety Goggles

Water

Sunscreen

Insect Repellant

Crack Hammer

Chisel

Shovel

Wrapping Paper for Specimens

Bucket

Sledgehammer (optional)

Prybar (optional)

Metal Detector (optional)

Description:

The Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan has been nationally famous for over 100 years for its history of highly productive copper mining. The local basalt is criss-crossed with many thick veins of native copper that made up the main ore of many of the mines. Solid natural masses of copper weighing hundreds of pounds were found with relative frequency at the mines. Though these pieces certainly were the most valuable ore, the best specimens from the area are clusters of well formed copper crystals. Other metallic minerals can be found with the native copper such as silver, domeykite, mohawkite, and chalcocite. Many other interesting minerals like datolite, analcime, prehnite, agate, and thomsonite are also abundant in the Keweenaw Peninsula. While all the mines of the region are closed to copper production, many are maintained as museums and fee dig sites. There are also many abandoned mines in the area that can provide good digging in the dumps but be sure to acquire permission from landowners before visiting any location on private land.

Localities:

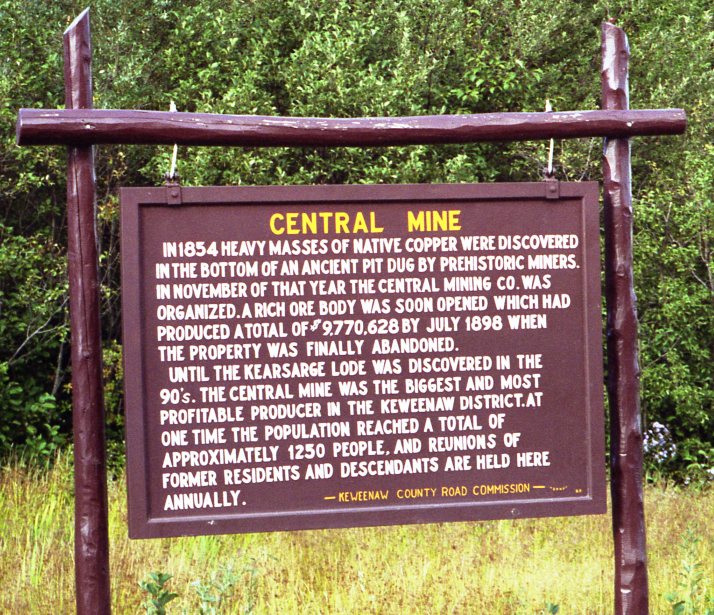

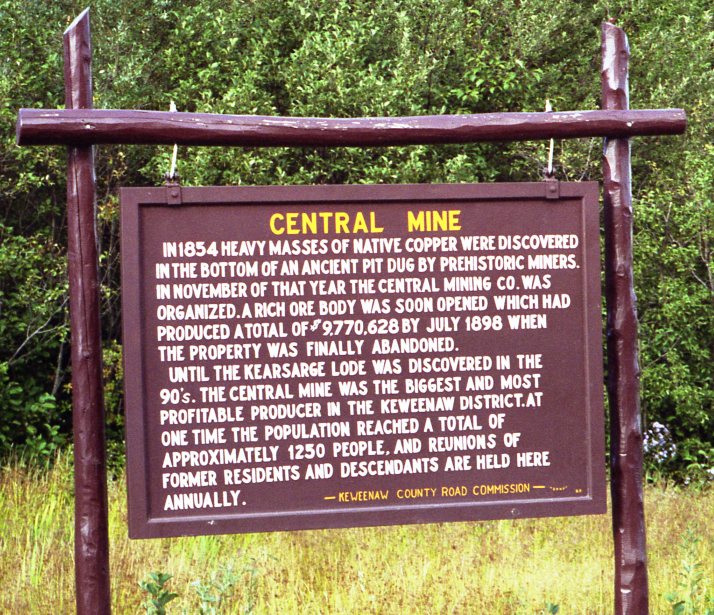

Central Mine:

US 41

Central, MI 49950

Photo by Dave Maietta

Map:

The large tailings piles of the Central Mine are visible from US 41 in Central, Michigan. Many collectors have had good luck recently working this location. Occasionally, contractors remove large quantities of tailings for construction purposes and this exposes fresh material. In addition to the standard copper specimens, copper included calcite and prehnite can be found here. Silver has also been found with copper here but it is rare. A metal detector is very helpful for sorting trough dump piles like those found at the Central Mine.

Caption: Calcite with copper inclusions. Central Mine, Central, MI 4.9 cm x 4.6 cm x 4 cm Ex. Rukin Jelks Rob Lavinsky Photo

Caption: Unusually large copper crystal. Central Mine, Central, MI. George Vaux collection at Bryn Mawr College. Scale bar is 1” long with rule at 1cm. Rock Currier Photo.

Caledonia Mine:

Website: http://www.caledoniamine.com/

906-370-1131

202 Ontonagon St,

Ontonagon

Michigan 49953

The Caledonia Mine is a fee dig site that requires an advance reservation. When digging at this site, collectors are given a large pile of stockpiled copper ore and tools to go through it. Weekly collecting events on Thursdays and Saturdays are also held from the first Thursday in June to the last Saturday in August on the ore pile. Advance reservations are needed for these too. The workings of the Caledonia Mine are impressively preserved and tours are offered too. The mine tours aren’t necessarily just geared for casual guests. Many kinds of tours are offered, some with a very in depth historical or scientific focus. It is best to check the museum calendar to see if any events are happening during the time of your visit.

Caption: Representative specimen of native copper from the Caledonia Mine’s recent workings. 5.6cm wide. Rob Lavinsky Photo

A.E. Seaman Mineral Museum

Website: http://www.museum.mtu.edu/

Michigan Technological University

1404 E. Sharon Avenue

Houghton, Michigan 49931-1295

E-mail: tjb@mtu.edu

Telephone: (906) 487-2572

Michigan Tech’s A.E. Seaman Mineral museum is among the finest mineralogical museums in the world. Its laboratories are also critical in performing much of the cutting edge mineral research currently being performed. During the period of most intense copper mining in Michigan, many specimens of local minerals were donated to the museum. Their collection of Michigan minerals is the finest in the world and there is a strong local emphasis on their displays.

Check out our custom search and view all the minerals from Michigan for sale on eBay. Not only will you see lots of neat stuff for sale, you’ll also get an idea of what localities are producing in the region.

|