Pecos Valley Diamonds, also called Pecos Diamonds, have been collected by New Mexico rockhounds and mineral collectors for well over one hundred years.

Like many other colloquial mineral monikers (another well-known example is “Herkimer diamonds”), these “diamonds” are not diamonds at all, but quartz crystals. The glint of reflected sunlight off the faces of these quartz crystals can give the barren desert the appearance of being “paved with diamonds” (Albright and Bauer 1955).

Article and Photos by Phil Simmons and Erin Delventhal at Enchanted Minerals LLC – enchantedmineralsLLC@gmail.com

Outcrops of Pecos Valley Diamonds are often densely concentrated. Each “pebble” in this image is a quartz crystal, most measuring ~1-2cm. Many crystals are broken. Field of view is approximately 1 meter. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

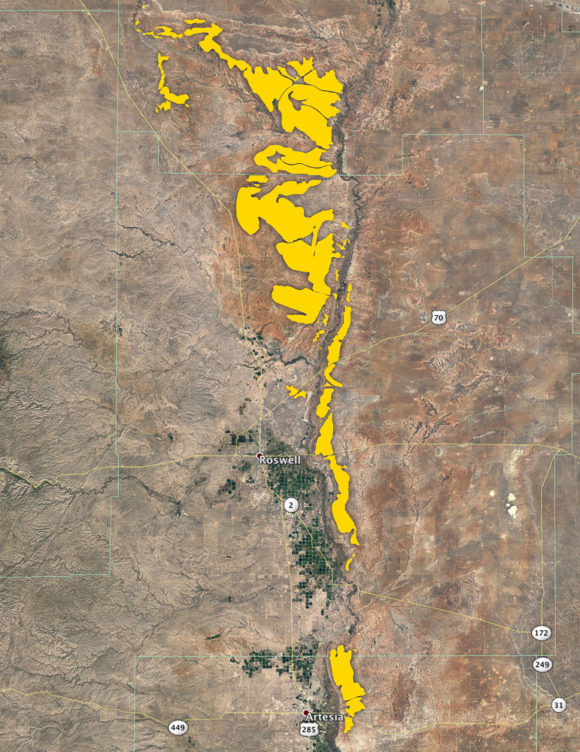

Pecos Valley Diamonds are found in the southeastern region of New Mexico, exposed in dispersed outcrops that span 100 miles long by as much as 25 miles wide. Though the area where outcrops are found is expansive, Pecos Valley Diamonds are limited to a very specific geologic unit: the Seven Rivers Formation, a back-reef segment of the Guadalupe reef sequence. The crystals are authigenic, meaning they have formed in place with no transportation via water or wind, though they often have weathered out of the much softer massive gypsum host rock. Though authigenic quartz crystals are known in ancient shallow marine carbonate and evaporite series across the world, Pecos Valley Diamonds are of note for their variety of colors and forms and for their impressive size (up to ~12cm, though more often ~2-3cm) for this type of deposit.

Surface outcrops of the Seven Rivers Formation (highlighted in yellow) in Southeastern New Mexico. Modified from Albright and Lueth 2003. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Habits and Variations of Crystals

One of the most appealing aspects of Pecos Valley Diamonds is the immense variety. They occur as doubly terminated crystals (less often in radial groupings) in a multitude of colors ranging from reds, oranges, and yellows, to whites, blacks, browns, and sometimes even hues of purples, pinks, and greens, and a variety of habits including prismatic, quartzoid, pseudocubic, and pseudotrigonal.

Coloration

A grouping of Pecos Valley Diamonds showing some of the range of coloration in the quartz crystals. Center crystal is 2.5cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

The wide variety of colors in Pecos Valley Diamonds has not yet been fully explored. Observational evidence indicates the coloration is largely due to inclusions: Pecos Valley Diamonds found still embedded in the host rock take on the color of the gypsum, even to the point of preserving the color banding found along laminations or fracture joints (Tarr and Lonsdale 1929).

Crystals displaying color variations within individual crystals. Top crystal is 3.5cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

The geological setting (see Geology below) of these crystals allows for the transition between gypsum and anhydrite, and zonal inclusions of anhydrite rather than gypsum have been reported (Nissenbaum 1967). However, the exact nature of those inclusions is still somewhat enigmatic: early reports refer to “ferruginous” (iron-rich) quartz or hematite inclusions in quartz, but analysis of similar quartz crystals from Spain indicate the red coloration is due to clay inclusions rather than hematite (Gil Marco 2013). Nearby occurrences of aragonite crystals also show coloration determined by inclusions of clay. Additionally, some coloration is suspected to be related to hydrocarbon inclusions (Albright and Lueth 2003). Of further interest, many of the quartz crystals are fluorescent, though the source of that phenomenon has not been explored.

A Pecos Valley Diamond embedded in the host rock of massive gypsum. These crystals appear to take the color of the surrounding gypsum, though the crystals tend to universally be darker. Specimen is 15.2cm across; crystal length is 3.4cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Prismatic Habits

An example of a fairly “typical” Pecos Valley Diamond – a doubly terminated prismatic crystal. The red coloration is also fairly common. Crystal is 5.9cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

The predominant habit found is single doubly terminated prismatic crystals with the regular m prism topped by hexagonal pyramids of equal or near equal r and z rhombs. This habit of quartz is common all over the world, although the majority of crystals worldwide are not doubly terminated. This habit tends to have the most color variations of Pecos Valley Diamonds. Elongated crystals are more rare than short, stubby crystals, though they can be found in several known locations.

Elongated prismatic crystals are unusual in Pecos Valley Diamonds. Longest crystal is 5.5cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Equant Habits

Though Pecos Valley Diamonds are most often found as prismatic crystals, the variety of equant (length, width, and depth are roughly equal) habits of quartz are of particular note.

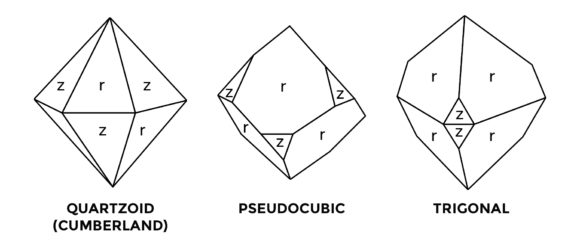

Crystal diagrams of equant forms found in Pecos Diamonds. Modified from Albright and Lueth 2003. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Crystals that display equal or near equal r and z rhombs, but significantly lacking m faces display a quartzoid, or Cumberland, habit. This habit is often erroneously referred to as beta-quartz, which is a high-temperature polymorph of SiO2 that is unstable at room temperatures. The presence of this habit in the low-temperature environments of Pecos Valley Diamonds indicates that the quartzoid habit is not tied exclusively to high temperature deposition.

Two unusual equant habits in worldwide deposits are relatively common in Pecos Valley Diamonds: the pseudocubic habit and the trigonal habit. Both are described by dominant development of r-faces with minimal z-faces and next to no presence of m–faces, though the latter two forms are never completely absent. The pseudocube and the trigon can be differentiated crystallographically by the orientation of z-faces: the pseudocube features alternating r– and z– faces across the a-axis, while the trigonal form shows r– and z– faces mirrored across the a-axis (see crystal diagrams above).

Comparison of equant forms with the left-hand side viewing the crystals down the c-axis and the right-hand side viewing roughly perpendicular to the c-axis. Top: quartzoid (Cumberland) habit; Middle: pseudocubic habit; Bottom: trigonal habit. Largest crystal is 2.1cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Pecos Valley Diamond pseudocubic crystals are of particular note: while the pseudocubic habit is very unusual worldwide, Pecos Valley Diamonds boast an unusually high percentage of crystals in this habit and crystals can reach sizes in excess of 5cm. Given the tendency for crystals to be fully formed and doubly terminated, coupled with availability, it can be argued that Pecos Valley Diamonds are the world’s best source for pseudocubic quartz.

Various orientations of the pseudocubic form in Pecos Valley Diamonds. Left-hand crystal is 2.5cm; largest crystal in center grouping is 2.7cm; right-hand crystal is 1.5cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Other Features

Pecos Diamonds often display different lusters on different quartz faces. This is typically found in lustrous terminations (r– and z– faces) and dulled, or pitted, m-faces. Luster can also vary between r– and z– faces, creating alternating finishes on terminations.

Two prismatic crystals displaying lustrous terminations (r- and z-faces) and dulled, or pitted, m-faces. Left-hand crystal is 3.0cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Examples of Pecos Valley Diamonds displaying both crudely crystalline “knobs” and well-formed, lustrous crystals. Clockwise from top left: crystal is 5.1cm; terminated crystal is 4.6 tall; crude crystal is 7.2cm across; crude crystal is 7.6cm across; right-hand crystal is 4.7cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Groupings

Radially oriented grouping of crystals; specimen shown front and back. Crystal is 3.8cm across. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

Previous reports (Albright and Lueth 2003) have indicated the presence of Japan law twinned Pecos Valley Diamonds, though it is the opinion of the authors that further examination is needed to determine whether these geometries are truly Japan Law twins. There are a number of other unusual relationships between multiple crystals that are also worth further investigation, including crystal pairs that show indications of potential relationships along the c-axis.

Unusual geometries in groupings of multiple crystals. Top left crystal is 3.1cm; top right crystal is 2.6; bottom right crystal is 3.1cm. ©Enchanted Minerals LLC

For more information on the History and Geology of Pecos Valley Diamonds, see the full-length article from Enchanted Minerals LLC: Pecos Valley Diamonds: the Desert is Paved with Diamonds.

Where to Go!

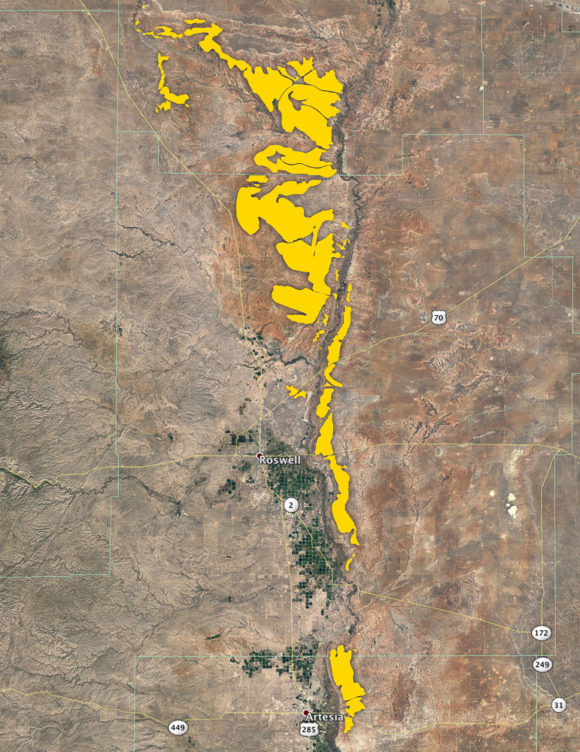

As mentioned earlier, outcrops of Pecos Valley Diamonds are prevalent throughout the Seven Rivers Formation – this means that anywhere in the yellow area below is prime territory to find them.

Surface outcrops of the Seven Rivers Formation (highlighted in yellow) in Southeastern New Mexico. Modified from Albright and Lueth 2003.

We’ll give you directions to a few of our favorite spots, but we encourage you to take some time to explore on your own! You never know what you might find – though please be sure to check land status of where you’re at and obtain proper permissions.

BLM land is fair game for surface collecting, but private land is not. Many cattle ranches operate in this part of New Mexico – many times you can simply ask permission and you’ll be good to go. Many oil and gas operations are also active in this area – surface collecting is legal around these operations, but be respectful of equipment (re: do not touch it), and also be very aware of any signs or warnings posted indicating the presence of H2S gas – it can and WILL kill you. In short: be smart and be safe while you’re out!

Location 1: East of Artesia (click for map)

Location 1 features small to medium dark red crystals – mainly equant crystals, sometimes pseudocubic!

Location 2: East of Roswell (click for map)

Location 2 features druzy crystals ranging from light to dark red.

Location 3: Acme – northwest of Roswell (click for map)

Location 3 is the site of the first professional paper published on Pecos Valley Diamonds (Tarr, 1929) – crystals are white to pink and usually do not exceed more than 2 cm in length, but this is a fun spot for the history!

Other things you need to know:

The southern region of New Mexico is barren desert. There’s usually not a tree, and if there is, it’s probably a short and stubby one. If you are going to this area during the summer, be sure to be prepared for the heat: pack lots of water, bring sunscreen, etc. Surface collecting without shade in July can be pretty miserable even with all these preparations, so we recommend that you take this trip in the spring or fall. Winter is also an option, but just as the desert is prone to extreme heat in the summer, it has a tendency to be bitterly cold in the winter. New Mexico in the spring time is also known for wind – this is an unpleasant thing when your face is inches from the ground and you can’t see anything except the sand grains in your eyes. There’s not much to be done about the wind, but be aware that it is a possibility.

Other things to do in the area:

If you’re making this trip, there are some other really fantastic things in the area worth checking out. Schedule some of these into your trip, or keep these as a backup option if the weather is poor for collecting.

Number 1 for us on this list is Carlsbad Caverns National Park – this is arguably New Mexico’s pride and joy, and is around 2 hours from Roswell, New Mexico. This National Park protects hundreds of miles of natural cavern systems, including it’s namesake Carlsbad Cavern. There are many things to do while in this park: walking trails, cave tours, historical stops, etc., but we absolutely recommend that you try to make it for one of the Bat Flight Programs that are held from late May through October – this experience is absolutely magical.

Rock of Ages in the Big Room, c. 1941; photo by Ansel Adams

Number 2: you’re near Roswell, New Mexico. You know what that means. Make a stop at the International UFO Museum and Research Center to explore your alien curiosity or grab some great knickknacks featuring little green men.

There are some other museums and parks in the Roswell area worth considering, including art museums, an aviation museum, and a number of wildlife refuges and bird sanctuaries. Check out some of the options here: Roswell Area Attractions. If you’re up for going out a little further, also consider: Carlsbad Area Attractions, and if you’re up for a real jaunt, consider White Sands National Monument and the White Sands Missile Range Museum.