Pyromorphite and wulfenite are highly sought after by collectors because they are some of the most intensely colored species in the mineral kingdom. Pyromorphite is known for its diverse hues and shapes ranging from vivid green, to yellow, to orange and from hoppered hexagon, to hexagonal prism, to semispheroid. Wulfenite almost always forms yellow to orange-red square shaped tabular crystals. When mineral collectors think of these minerals, exotic international locations pop into their heads like China, Arizona, Idaho, Namibia, Morocco, and Mexico. Little do many mineral enthusiasts in the Northeast US know, there is a wonderful site to dig these minerals in Massachusetts. It is just rarely represented in the specimen market because the crystals are smaller and less abundant than the really famous spots. Regardless of that, most collecting sites in New England don’t provide vibrantly colorful and diverse oxidized minerals like this place, and none exist where you can pan for wulfenites in the river like you can at Loudville!

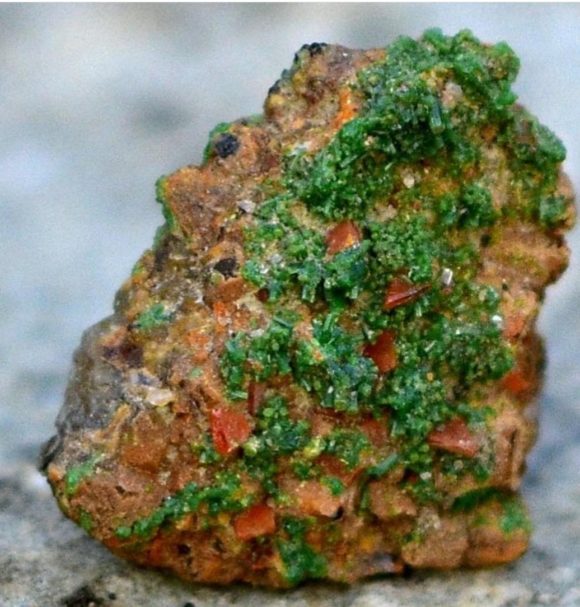

Beautiful combo of pyromorphite and wulfenite dug by my friend Alex Kim (@dirty_minerals on insta). Finding this piece is what inspired him to dig minerals. Check out more of his collecting adventures and amazing finds on his page!

History: The name “Loudville Lead mines” is used to refer to the many mines in a small district adjacent to the Manhan river in Northampton, Mass. Loudville is the name of a small village in the area on the Easthampton and Westhampton line that was the nearest settlement during mining activity (2). The Loudville Lead mines are some of the oldest colonial mines in the US. Discovered by Robert Dyer in the late 1670s (1), they experienced several periods of mining from the 17th through 19th century. The first phase was from discovery until the American Revolution, which halted operations. I have heard though I cannot confirm that lead from Loudville was used in Revolutionary munitions like musket and cannonballs. Ethan Allen, famous hero of the American Revolution worked Loudville in the late 1700s after giving up prospecting Mine Hill in Roxbury, CT for silver (3). This mine was worked intermittently throughout the 19th century, last in 1865.

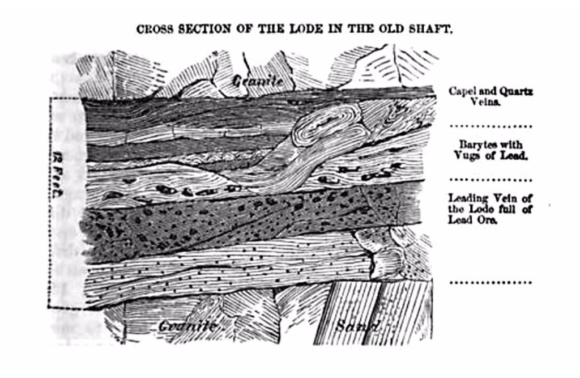

an early sketch of the geology of the lead ore vein at Loudville from

Richardson, Charles (1854): Northampton District. The Loudville Mine (Mining Magazine Vol. 2 pp 13-20.

Mineralogy: Pyromorphite and Wulfenite are the most sought after minerals at this location and often they are hard to see. When you find material that shows any hint of green or orange, save it and delicately clean it at home. Do not use chemicals on minerals from Loudville with the exception of quartz. Many of these minerals will react even with iron out.

Secondary, oxidized minerals like Wulfenite and Pyromorphite are extremely rare in New England. Many of the oxidized zones (called supergene zones) of metal deposits in the region were removed by glaciers leaving mostly just sulfides which generally are massive and not aesthetic at the majority of locations in the region. Finding just one pyromorphite or wulfenite crystal at a lead deposit almost anywhere else in New England is a very rare experience.

Gorgeous specimens of pyromorphite collected by my friend Dustin Bartlett (@themodernnaturalist on instagra,) Dustin has collected Loudville extensively and his page is a good place to go to see what collectors are still finding there!

Lead secondary minerals such as cerussite, anglesite, and the rare leadhillite are also found at Loudville. Cerussite is expecially common and overlooked. The best way to spot it is by its high luster and understanding its unique crystallography. Frequently it exhibits twinning. Even though it is colorless, its appearance makes it immediately distinguishable from quartz and baryte- the two other colorless minerals here. The author has collected numerous fine cerussites at Loudville to nearly 2cm long.

Quartz is another very common mineral at Loudville that can be very pretty. Beautiful clusters of milky, smoky, amethystine, and combos of these three varieties of quartz can be found, crystals getting quite large! Many of the similar lead mines in the Northeast such as the closed to collecting Canton Lead Mine in Ct are known for colorful amethyst and smokies with lead secondaries. At Loudville, you will often find other minerals, especially pyromorphite and wulfenite coating the quartz.

Beautiful combo of pyromorphite on dark smoky quartz dug by Dustin Bartlett @themodernnaturalist on insta

The list of minerals at Loudville is extremely extensive and represents so many interesting combinations of lead, zinc, copper, sulfate, carbonate, silicate, etc. Under the microscope, a whole world of collectible material becomes available. Please see Mindat if you want to learn more: https://www.mindat.org/loc-3832.html

Directions and Equipment:

When digging here, please respect the boundaries to the collecting area! There has been a lot of digging outside of it and if it continues, the site may be closed within the next few years. Saying that, there are many strategies to collecting there, I will discuss two of them.

The first strategy involves digging into the dump and breaking rock to expose vugs. Use a shovel, hand rake, etc to turn over the dump and a crack hammer and chisel to break the material. The river is a convenient source of water to wash pieces off you can’t see clearly. Often the mud can obscure the crystals. Move slow and be careful.

An especially interesting technique people have been successful with here is panning for wulfenite in the river using a gold pan. Wulfenite is very dense compared to other minerals and will readily separate out in your concentrate. Use tweezers to pluck them out and I strongly advise you put them into a vial of water since they are fragile and very easy to lose.

In addition to the tools I outline above, other things you will want to bring is food, water, bug spray (it gets bad in the summer), sunscreen, and waterproof footware. This is a great place to bring dogs as many of them love swimming in the river. Just keep them on leash and be respectful to other dog owners.

To get to the site, it is very simple. Navigate to the pin on the embedded map and look for a small parking area. Park there and make your way down to the edge of the river. The collecting areas are clearly marked.

Article By Jeremy Zolan

Sources:

https://www.mindat.org/loc-3832.html

(1) Trumbull, James R. (1898): History of Northampton Massachusetts from its Settlement in 1654, Gazette Printing Company, Northampton Massachusetts: 358-368.

(2) Robinson, G.R. Jr., and Woodruff, L.G. (1988): Characteristics of Base-metal and Barite Vein Deposits associated with Rift Basins, with Examples from some Early Mesozoic Basins of Eastern North America, in Studies of Early Mesozoic Basins of the Eastern US, Frolich, T.J. and Robinson, G.R. Jr., Editors, USGS Bulletin 1776: 377-390.

(3) Hall, Henry (1895). Ethan Allen: the Robin Hood of Vermont, Appleton and Company, New York.