The Himalaya Mine is a location that rock and mineral collectors dream of: rich mineralization featuring gem minerals in stunning color! The extraordinary minerals that come from this mine have made it world famous – lucky for you, the mine offers a pay dig site where you can keep all you find!

Before we get to the pictures of pretty minerals, let’s talk a little about the history of the Himalaya Mine! (If you really can’t handle this part, you could scroll past, but you’d be missing out on some cool stuff!) The Himalaya Mine was officially located in 1898, though early reports indicate that local Indigenous Peoples knew of the gem crystals. Legend has it that white settlers located the mine after noticing Indigenous children playing with tourmaline crystals!

Gail Lewis was the original claim holder on the mine, though only held the property for four years. In 1902, J.L. Tannenbaum, an employee of Tiffany & Company and a very controversial man, acquired the property through claim jumping. Keep in mind, this is the original usage of the term “claim jumping,” meaning Tannenbaum filed another claim over the top of Lewis’ existing claim. Much legal to-do ensued over this, but Tannenbaum retained the property. The mine was then operated by Tannenbaum with J. Goodman Braye as mine superintendent. Braye is a very interesting figure in mining history, as his position as superintendent was one of significant power and respect and he also happened to be an African American in the early 1900s.

Original caption: “First workings on the Himalaya mine at Mesa Grande, which was later to become one of the greatest tourmaline producers in the world. Left to right: Heighway, who filed on the Himalaya for Tannenbaum of New York; Vance Angel (center above) who was foreman 1900 – 1912; J. Goodman Bray, Jr., colored protege of Tannenbaum who was in charge of the Himalaya; Lohrer, first foreman of the mine; La Chapa, Indian worker. Photo courtesy Vance Angel, Mesa Grande.” Reprinted from the bimonthly magazine Calico Print, Vol. IX, No. 4, July 1953, 40pp. The Calico Press, Twentynine Palms, California.

In the following ten years, reports indicate that 6 tons of tourmaline were shipped for use as lapidary material out of an estimated production of 110 tons produced by the Himalaya Mine and neighboring mines. This would equal value at the time of more than $750,000! By 1904, the surface workings were mined out and work had moved underground.

One of the principal demands for tourmaline was overseas in the Chinese market, where pink and red gemstones were highly prized by the Dowager Empress. This drove a highly speculative market until the overthrow of the Chinese aristocracy in 1911. The downfall of the Chinese aristocracy caused the tourmaline market to crash and ended the early production period at the Himalaya Mine.

Pink Tourmaline snuff bottles – 19th century – Qing Dynasty – photograph from Christie’s Auction House.

Sporadic small scale mining operations continued between 1913 and the early 1950s. In 1957, Ralph Potter began another attempt at systematic mining at the Himalaya, including rehabilitating several older underground workings and driving several new tunnels. Potter operated the mine for several years, but a collapse of the main tunnel in the winter of 1968-1969 ended underground mining.

In 1977, Bill Larson of Pala Properties International leased the property, later purchasing it in 1988. This period saw extensive tunneling and underground expansion, and produced a relatively consistent stream of minerals in comparison to earlier projects.

The Himalaya Mine is now operated by High Desert Gems & Minerals, who also facilitate the pay dig site.

Over its life, the Himalaya Mine has produced an estimated 250 thousand pounds of tourmaline and mineral specimens. In its most active 15 years, it produced more tourmaline than any other tourmaline mine in the world, including 5.5 tons in 1904 alone (the most tourmaline ever produced in a year).

For more on the history of the Himalaya Mine, see:

Fisher, J., Foord, E. E. and Bricker, G. A. (1999), The geology, mineralogy, and history of the Himalaya mine, Mesa Grande, San Diego County, California. California Geology 52(1): 3-18.

Jacobson, Mark Ivan (September 2010): Lippman Tannenbaum: President of the Himalaya Mining Co. and a Difficult Person, Mineral News, Vol. 26, No. 9.

Jacobson, Mark Ivan (January 2017): The Early History of the Himalaya Pegmatite Mine – San Diego County, California, Mineral News, Vol. 33, No. 1.

So, what you really want to know: what can you find?!

Tourmaline – Elbaite:

Tourmaline, Lepidolite, and Quartz – 14 cm across – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

The Himalaya Mine’s most notable mineral is tourmaline, a complex hexagonal boron-aluminum-silicate mineral group. Most tourmaline from the Himalaya Mine is the species elbaite. The tourmalines can range in color from black to vivid pink to apple green, and some crystals even feature multiple colors! Blue tourmaline is also present, but is rarely found.

Approximately 5% of tourmaline from the Himalaya Mine are gemmy, meaning they have the high translucency that allows them to be faceted into glassy gem stones.

Elbaite – a gemmy crystal showing greens and pinks – 3.9cm tall – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Lepidolite:

Lepidolite on Hambergite – 4.5cm tall – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Lepidolite is a series of the mica group minerals. Lepidolite is rich in lithium, though the pink to red color of lepidolite is usually attributed to manganese content. Because lepidolite is a mica group mineral, it is often very flaky, but some material can be used in lapidary work.

Quartz:

Quartz on Microcline – 7.8cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Since the Himalaya Mine is a pegmatite mine, quartz is common throughout the deposit. It can occur as clear “rock crystal” quartz, milky quartz, and even smoky quartz. Some top specimens feature tourmaline or other minerals attached to quartz in beautiful ‘combination’ specimens.

Elbaite on Quartz – 6.0 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

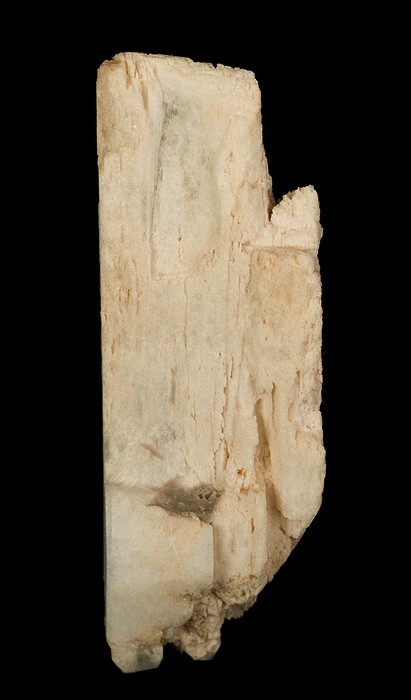

Microcline:

Microcline (Carlsbad twin) – 6.0 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Like quartz, feldspar is an integral part of the mineralogy of the Himalaya Mine. The most common feldspar species found is microcline. Microcline from the Himalaya Mine is often beige to colorless, and can featured etched surfaces as well as crystallographic twinning. Microcline is rarely gemmy from anywhere in the world, and this is also true at the Himalaya: it will likely appear as blocky opaque white-ish crystals.

Etched Microcline (twinned) with Albite and Lepidolite – 10.1 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Albite – variety Cleavelandite:

Albite on Orthoclase with Tourmaline – 8.6cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Albite is another of the feldspar species present at the Himalaya Mine. It often occurs as the variety Cleavelandite, which occurs as thin, platy crystals. Cleavelandite at the Himalaya Mine often occurs in beautiful rosettes of colorless to very faint blue, and can often be somewhat translucent.

Albite on Microcline with Quartz and Lepidolite – 25.0 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Fluorapatite:

Apatite – 2.3cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Fluorapatite from the Himalaya Mine is a uncommon, but is worth looking for! Colors range from colorless to blue to intense pink. Fluorapatite from the Himalaya Mine is light sensitive, so be prepared for colorless crystals on the surface and be sure to protect any colored crystals you happen to find.

Apatite on Quartz – 4.1cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

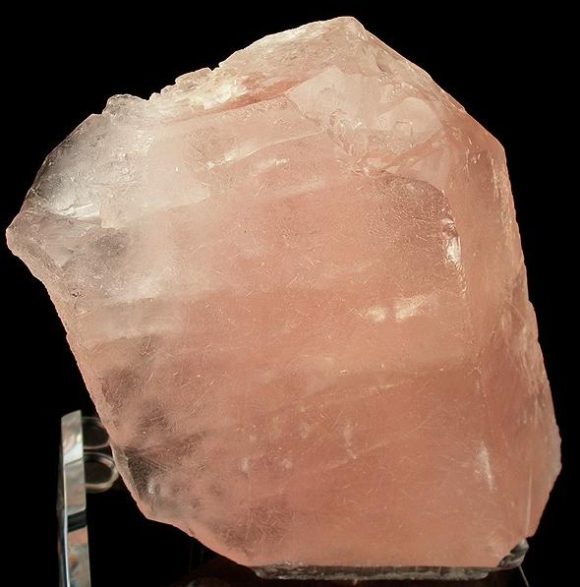

Beryl, topaz:

Beryl (etched) – 2.9cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

While beryl and topaz do occur at the Himalaya Mine, they are exceedingly rare. Keep an eye out for oddities though – you could get lucky! Beryl can occur as etched “floater” crystals, though fully formed crystals have also been found. Beryl colors at the Himalaya include goshenite (colorless), morganite (pink), and aquamarine (blue). Topaz is so rare at the Himalaya that we couldn’t even find a photo to share with you! Both beryl and topaz will likely look much like quartz, though there are physical qualities to help distinguish them – be sure to make use of the staff at the mine to help answer questions you have about your finds!

Beryl (morganite) – 11.7 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Hambergite:

Hambergite – 4.4cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Hambergite is another relatively rare pegmatite mineral that often occurs with beryl. Well-formed crystals of hambergite are hard to come by from anywhere in the world, but they can be found at the Himalaya Mine. They occur as creamy white crystals, but can also range from an orange-ish tint to a salmon orange-pink. They are sometimes opaque and sometimes gemmy, sometimes etched and sometimes sharp. Again, if you have questions about what you are finding, ask the staff – they’ve seen a lot of this material and have a lot of knowledge to share!

Hambergite – 2.9cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Stilbite:

Stilbite-Ca – 5.5cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Stilbite occurs at the Himalaya Mine as white to cream colored crystals often found in “wheat sheaf” shaped sprays of crystals. Stilbite is technically a super group of zeolite (framework alumosilicate) mineral species, but that chemistry makes it even more interesting at this locality! Stilbite rarely makes stand-alone specimens at the Himalaya (though that’s still possible!) – but look for it in combination with other minerals!

Stilbite on Tourmaline – 2.8 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

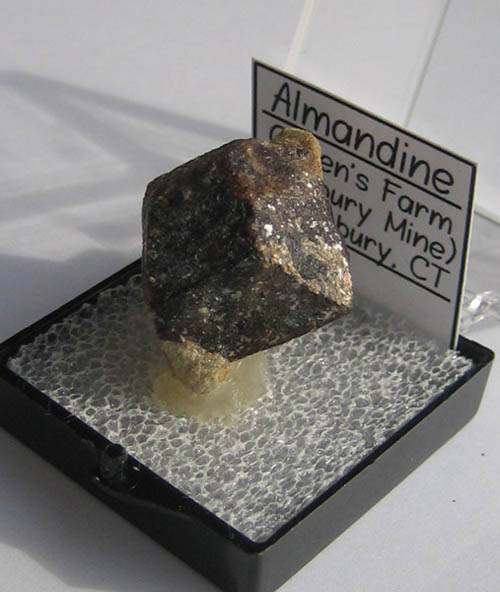

Stibiotantalite, Columbite-(Mn), and other “ugly” minerals:

Stibiotantalite (zoned) – 1.8cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

For those of you who also love the “ugly” minerals of the world, keep an eye out for some of other pegmatite rarities: stibiotantalite and columbite-(Mn)! These minerals will occur as black to root beer brown colored crystals, usually with a somewhat flattened shape. Some stibiotantalites even exhibit a beautiful color zoning! These minerals, though lacking the vivid colors of some of your other possible finds, have a fascinating chemistry (they include rare elements like tantalum and niobium!) and are fairly rare in worldwide deposits – don’t throw them away!

Stibiotantalite on Tourmaline – 6.0 cm – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

There are a few other minerals we haven’t mentioned (mostly because they’re super rare or uninteresting or both), but you can see a complete list and more photos on mindat.org here: Himalaya Mine, Gem Hill, Mesa Grande Mining District, San Diego County, California, USA.

Dig info:

Himalaya Mine Finds! – photograph from Himalaya Tourmaline Mine.

So now that you’re ready to pack the car and go, here’s the rest of the important information you need to know!

The Himalaya Mine dig site is open year round on Thursdays through Sundays from 10am to 3pm (Monday digs can be arranged by reservation only). The mine is located near Santa Ysabel, California and is open to the public. Visitors can dig and screen through ore from the mine in search of pink, green, and black tourmaline, quartz, garnet, lepidolite, cleavelandite, and more!

Screening for Gems – photograph from Himalaya Tourmaline Mine.

The cost for adults is $75/day, 13-15 years old is half price ($37.50/day), children 12 years and under are free with a paying adult, and additional children are $20/day. Senior and active military discounts, rain discounts, and group rates are available.

Be prepared to go digging: it’s going to be dirty and weather is going to happen. Be sure to bring appropriate gear (sunscreen, raincoats, shoes that can get muddy, etc.) as well as food and water. Sorting through material can be made easier with toothbrushes and rubber gloves. Don’t forget baggies/buckets and wrapping material for your finds!

How to Get There:

LISTEN UP, FOLKS! Do NOT use Google Maps or Map Quest to take you to the “Himalaya Mine” – this will NOT take you to the right location and you will end up LOST!

Instead, use the address Lake Henshaw 26439 Hwy 76, Santa Ysabel, CA 92070 to take you to Lake Henshaw Resort. You will need to go into the store (across from the lake and in the same building as the restaurant), ask for the mine dig, and the cashier will give you a code and further directions.

Make use of the MAP provided by High Desert Gems & Minerals by clicking here.

Be sure to check out High Desert Gems & Minerals’ website for any further information on the dig: Himalaya Tourmaline Mine Dig.

Himalaya Mine Tourmaline – photograph from the Himalaya Tourmaline Mine.