I enjoy seeing rocks light up under Short Wave Ultra Violet light, so do millions of other people in the world. It is exciting to see brilliant colors coming from, what commonly is, a not very visually stunning rock. While large exotic crystals can fluoresce, many times it is something drab and visually unappealing that shows brilliant reaction to “black light”. As the field trip leader for an active group of rock hounds, my monthly trip for February of 2017 was to the area known for brightly fluorescent rocks in the Shadow Mountains, just West of highway 395, in the high desert of Southern California.

Every month we lead a field trip for the Mining Supplies and Rock Shop in Hesperia California, visit the shop and join us!

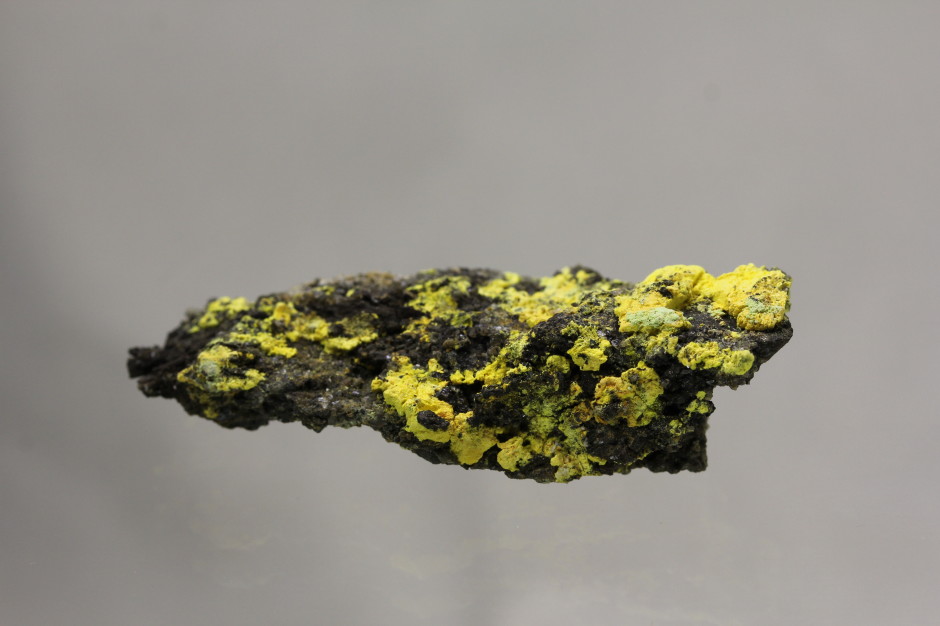

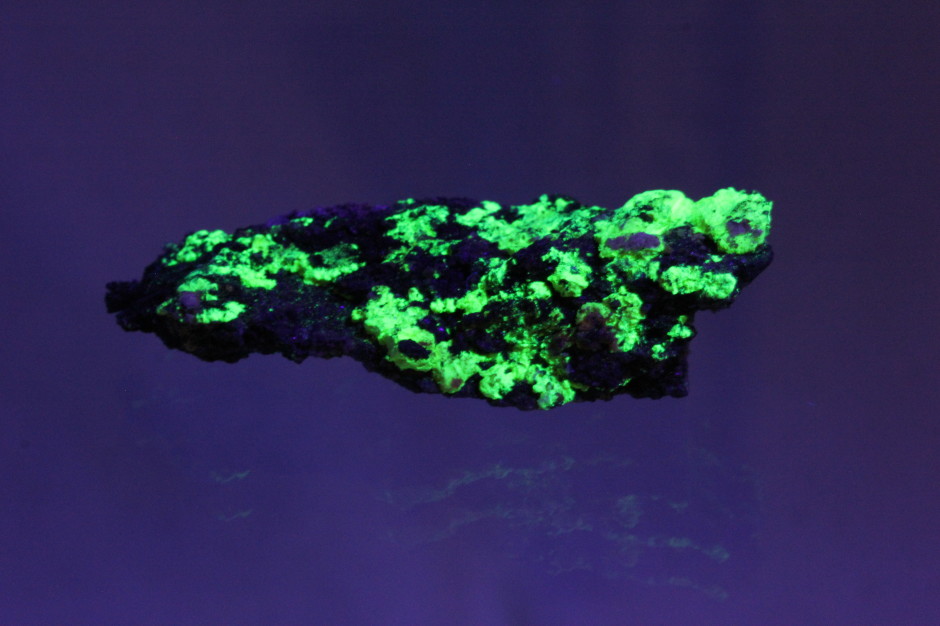

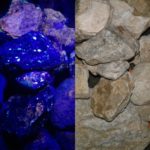

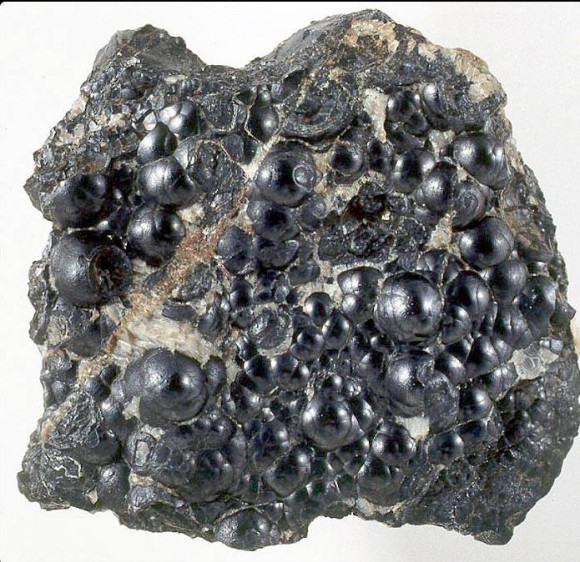

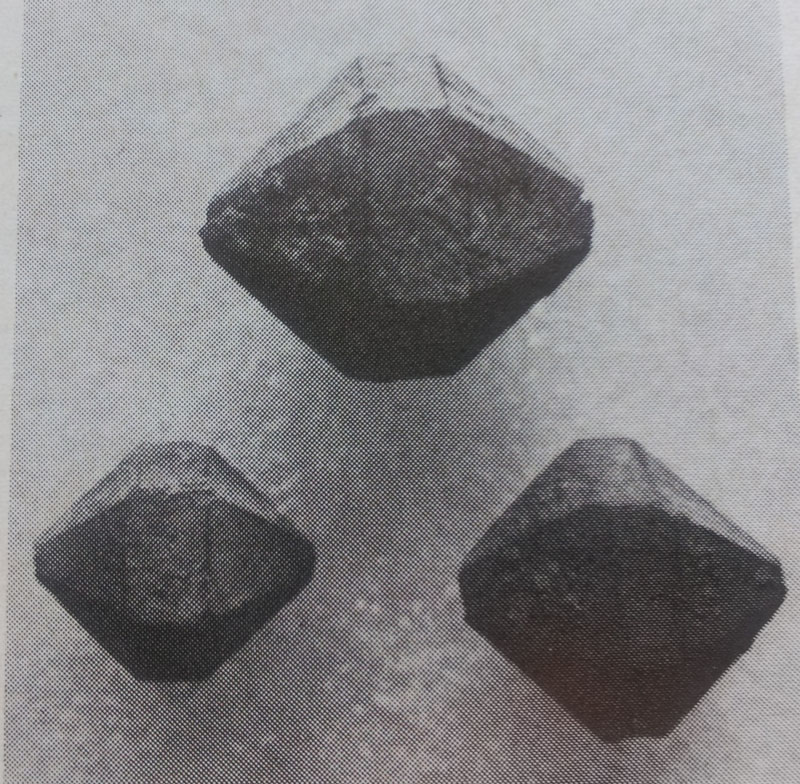

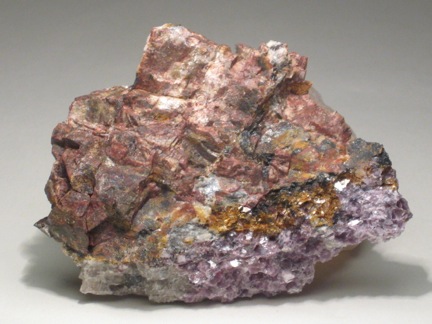

This photo shows the typical rocks found at the Shadow Mountain Tungsten District under normal light and under SW UV light.

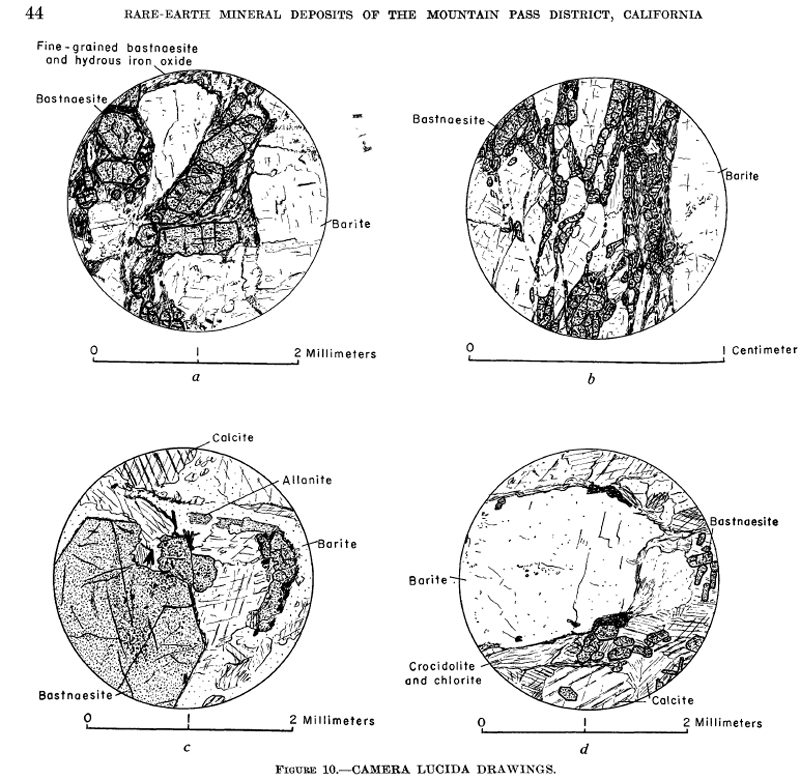

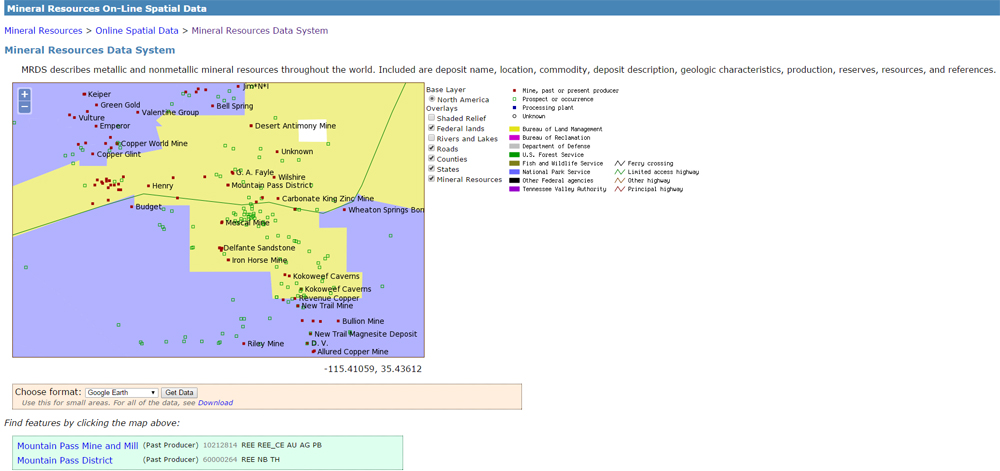

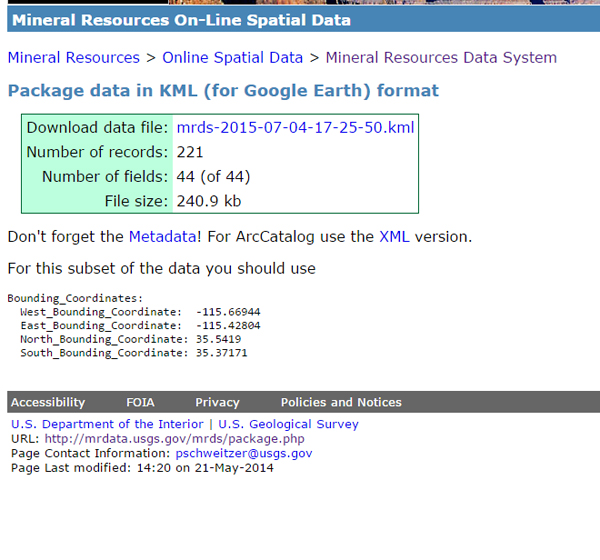

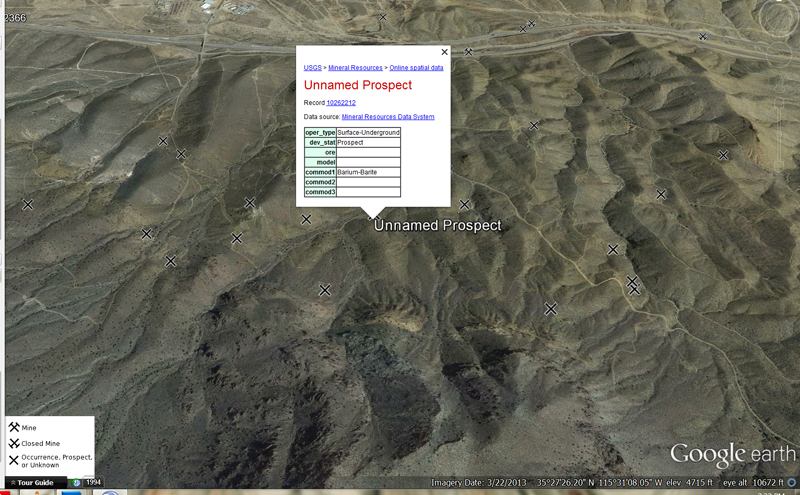

To start out my planning for this trip, I did a basic Google search for what I thought the name of the mine was, the “Princess Pat Mine”. Google brought up some pages with various bits of information, some photographs, but no real indication of where the mine was specifically located. I then turned my attention to MRDS, as talked about in Rockhounding 101, this site can give me a list of mines, pinpointed on a map, showing what has been found in the area. It was a surprise to see that while there were a dozen or more deposits for Scheelite, the highly UV reactive mineral we were after, none of the mines were called “Princess Pat”. However, looking at the Google map, I noticed the road that takes you right to the majority of the scheelite deposits was called “Princess Pat Mine Road”. In fact, you simply turn west off the 395 onto this unmarked road and go for 5 miles until you hit the collecting area. But, why was I having such a pain finding the “Princess Pat Mine”?

I broke open Pemberton’s “Minerals of California” to find an entry for the Shadow Mountain Tungsten deposits on page 337, where it states “6. In the Shadow Mountains, on the northwest flank of Silver Peak, there are a number of scheelite deposits consolidated as the Just Associates quarries. The scheelite occurs in quartz veins cutting garnet-epidote-quartz tactite.” – however, no mention of the “Princess Pat Mine” – So, could it have been that the name “Princess Pat” was older or newer than this 1983 tome of California minerals? With this, I pulled out the Murdoch and Webb version of “Minerals of California”, 1966 edition, which leaves out the Shadow Mountain tungsten mines from the entries on scheelite in San Bernardino County.

Luck would serve me up a reference to “California journal of mines and geology”, Volume 49, which featured a fantastically in depth article on ore bodies of San Bernardino County, which reads

Just Tungsten Quarries (Just Associates, Princess Pat, Shadow Mountains Mines). Location: sees. 30 and 31, T. 8 N., R. 6 W., S.B.M., on

the northwest flank of Silver Peak, Shadow Mountains, about 13 airline miles west of Helendale and 14 airline miles northwest of Adelanto.

Ownership : Just Associates, E. Richard Just and Oliver P. Adams, 726

Story Building, Los Angeles, California, own unpatented claims totaling 440 acres. The property is leased to Just Tungsten Quarries, E.

Richard Just and associates, 726 Story Building, Los Angeles, California.The deposit, now known as the Just Tungsten Quarries, was discovered in 1937. Operations from late 1937 to early 1938 by the Shadow

Mountains Tungsten Mines and W. A. Trout and C. A. Rasmussen re-

sulted in the recovery of about 750 units of W0 3 from nearly 3000 tons

of selected ore treated in a 40-ton mill on the property. The operation

was not successful and the mill was dismantled. During the mid-1940 ‘s

lessees mined about 400 tons of ore, and during the late 1940 ‘s the

Princess Pat Mining Company leased the property but apparently produced no ore. Operations from April 1952 to mid-1952 have yielded a

few hundred tons of ore of undisclosed grade.The scheelite occurs in quartz veins cutting garnet-epidote-quartz

tactite bodies which exist at the contact between a Mesozoic granitic

rock and Paleozoic ( ?) metamorphic rocks, mostly impure limestone and

schist. The foliated rocks strike slightly north of east and dip gently

south. Scheelite-bearing tactite also has been developed, away from the

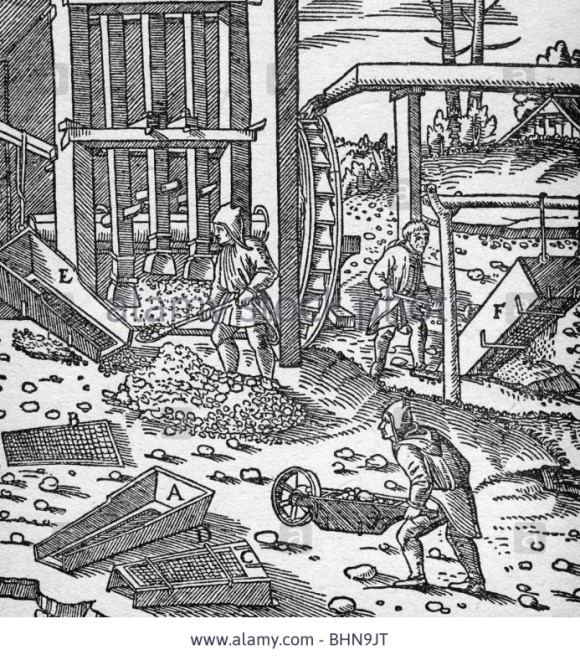

contact, along beds in the limestone, to form thin bodies of ore separated by barren limestone beds.The deposit was explored during 1937-38 by 1800 feet of zig-zag

trenches, 10 feet wide and 6 to 10 feet deep, excavated by a power shovel

up a moderate slope in a southwesterly direction. A 65-foot vertical shaft

was sunk near the lower end of this trench system, but no mining was

done underground.Employed in the early prospecting was a large field-type lamp requiring a 110-volt current, and a portable gasoline-powered motor generator set. This may have been the first practical application of a lamp

of this type.Ore is being mined from a bench cutting into a trenched area about

50 feet north of the shaft. Mining operations are carried on at night,

and the ore is sorted with the aid of ultra-violet light. Shipments have

been made to both the Jaylite and Parker custom mills in Barstow.

There you go, the “Princess Pat Mine” has the distinction of being a mine that produced no ore.

As it was, the tungsten mines produced little more than some naming confusions and quite possibly some bad debt, as the scheelite riches would never quite materialize from this deposit. Tungsten is an element that was listed by the United States Government as a strategic reserve, as most of our Tungsten comes from China, during WWII it was known that it would be scarce, so efforts were made to ensure production could be met at home. Plenty of trenches and tunnels were driven in this 140 acre unpatented claim, in the end, producing nothing more than a playground for collectors with an UV light.

The mostly smooth desert road is littered with rocks that glow under SW UV light

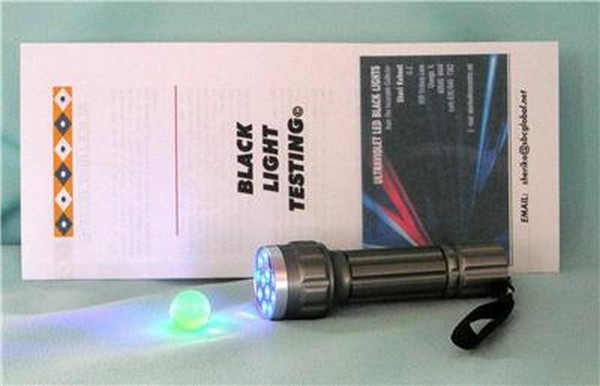

There is often a little confusion as to what kind of Ultra-violet light one needs to get the enjoyment out of collecting UV minerals. I have used many varieties of products and I’ve found what I like and what I do not like. Obviously, a light with ample power is what one wants. Small hand held units are commonly available in 6 watt and under, which gives you a reaction when you hold the light VERY close to the specimen. However, the difference between a low wattage light and something in the 9, 18, or even, 36 watts will astonish every viewer. If you want maximum enjoyment out of UV collecting, a dual wave 18 watt light is a sound investment. Some minerals glow under Long Wave (365nm) range, but honestly, I find Long Wave to be the most limited, while Short Wave (285nm), produces amazing effects. When it comes to companies, well, some come and some go, while some are longstanding companies that I do not personally enjoy, when it comes to price vs. what you get, so, I would like to steer you in the right direction. At this time, in winter of 2017, there are no good companies to purchase a UV light from on Amazon.com. In fact, I would push you in two directions. #1, UVTools.com – They have been producing some fine lights, which come accompanied by a great informative kit. I highly recommend all the units they sell, even the sub-9 watt lights. #2, on eBay, the seller topazminer_minerals_and_fossils has been having great deals on a fine selection of high powered lights, at very reasonable prices. I would suggest viewing their offerings when looking for a great UV light.

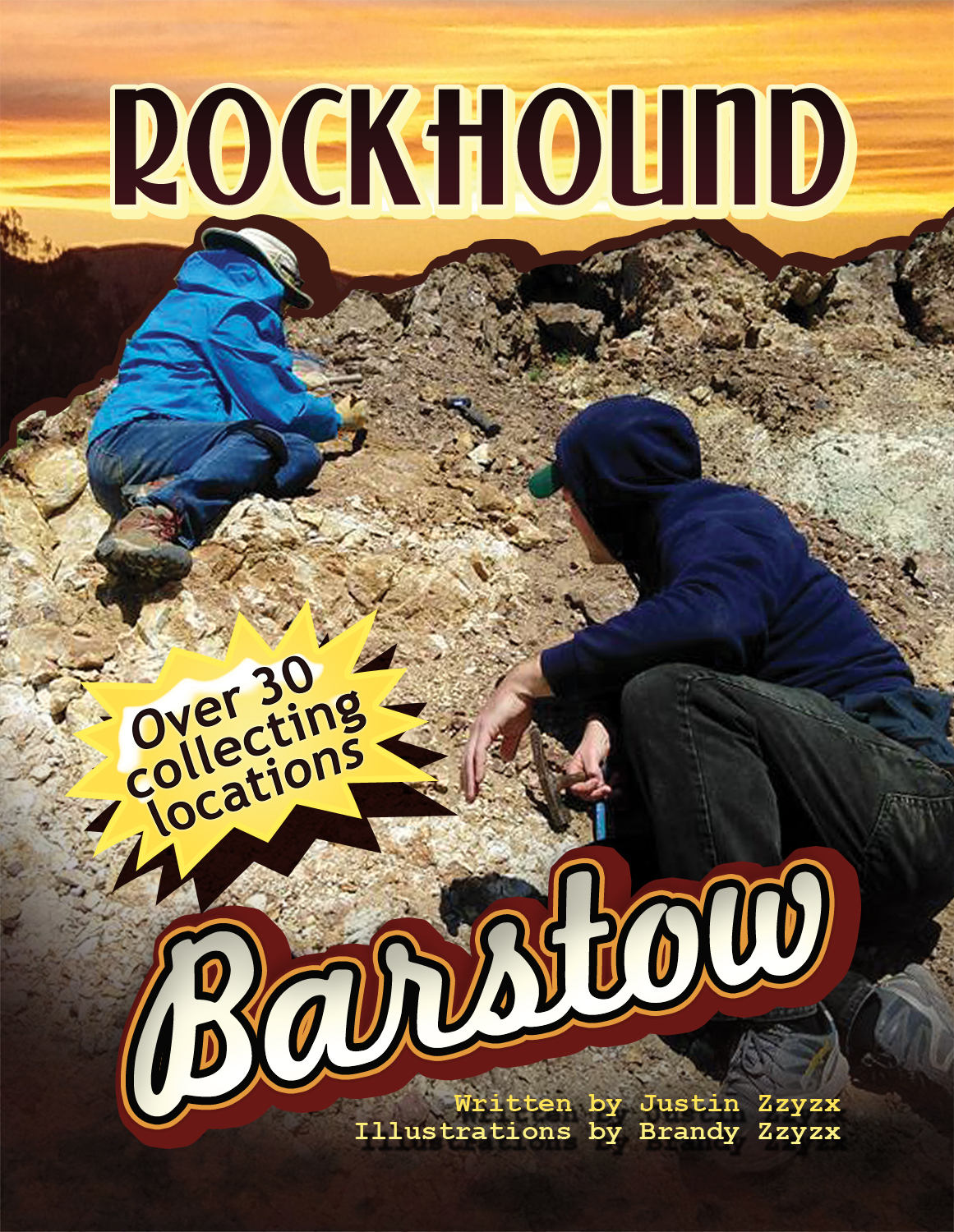

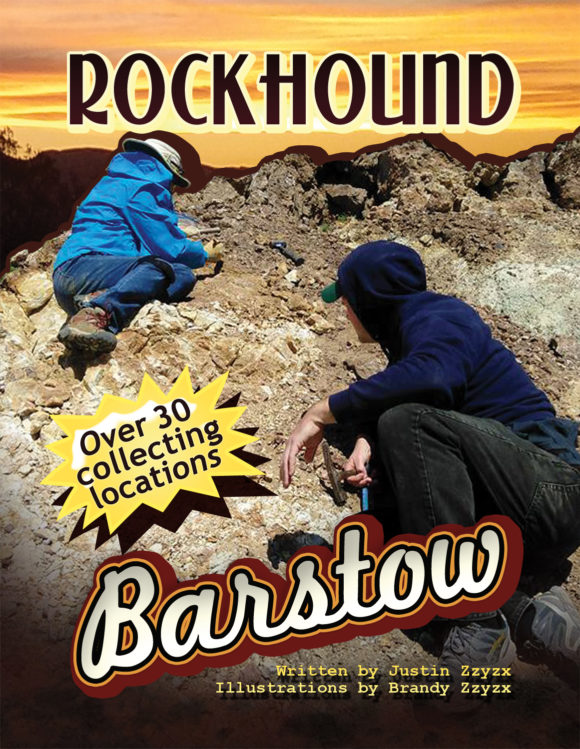

If you like this article, check out the 28 page full color field guide “Rockhound Barstow” for sale online at the following links, now including the Princess Pat Mine Area, indepth!

Buy it on eBay

Order it on Amazon, or Buy it for Kindle eBook Readers

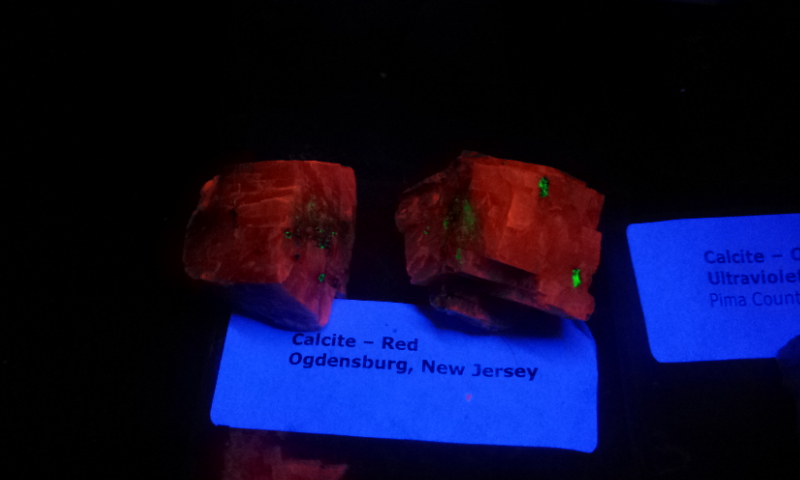

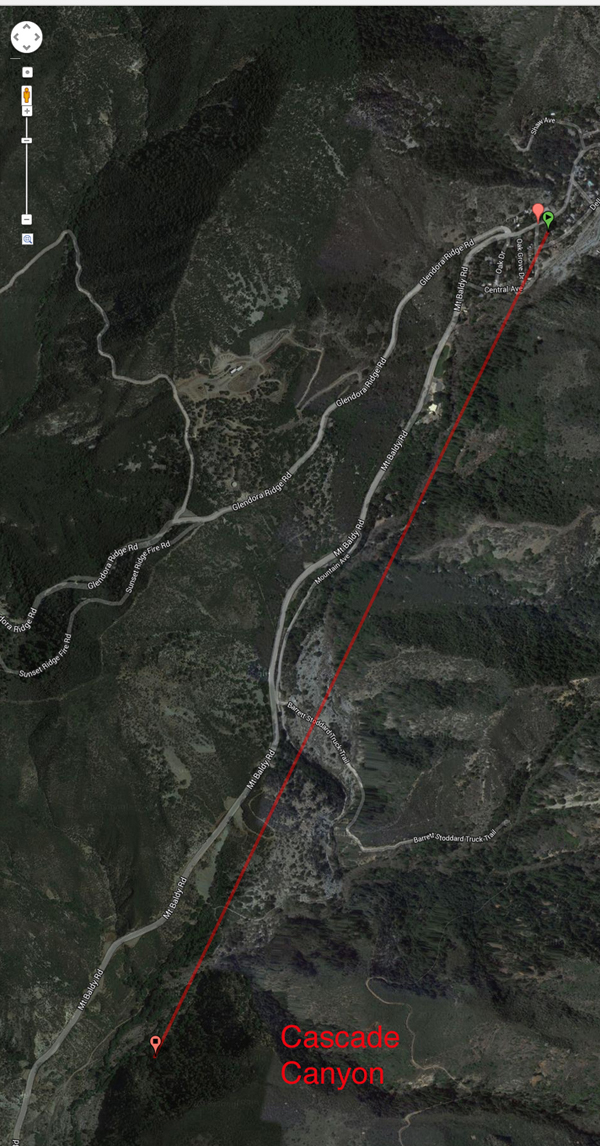

As part of the field trip series that I lead for the Mining Supplies and Rock Shop in Hesperia California, we took a trip out to the “Princess Pat Mine” area, or, as it should be known, the Just Associates Tungsten area, or, even still, the Shadow Mountain Tungsten area. You simply follow Princess Pat Mine road from highway 395 for 5 miles and you will find yourself facing the various prospect pits and trenches filled with cobbles and boulders of mostly white rocks that will glow readily under short wave light. You will see bright orange from the potassium rich calcite caliche, you’ll see bright green from the uranium included quartz. The bright white/blue scheelite is the real winner, appearing as belts of star-like dots in the rocky background. Rarely, one can find bright red from the wollastonite found in the area.

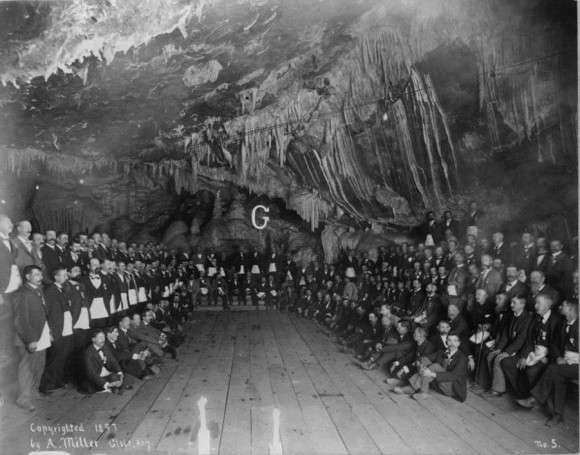

We have lead field trips for various groups and organizations

This pile of ore rubble was waiting for us at the parking area 1/10th of a mile from the start of the major trenching. This pile of rocks glows brightly if you do not wish to go into the rocky tailings beyond.

A group of about 30 of us descended on the mine area around 5pm, getting a view of the area before the sun set, by 6pm we were ready to see some rocks glow! Many of us came equipped with various powered UV lights. Some of the inexpensive LED Longwave lights were causing the calcite to glow a slight pinkish, but that was all, while the Shortwave lights were causing the whole area to light up. Everything around the area was glowing light wild, which lead to lots of happy rockhounds and many people remarking that they could not wait to come back and bring friends to show this wonderful area to. In this lonely desert, with no lights besides the moon and the stars, one can get some amazing results with a short wave ultra-violet light!

There were plenty of trenches pushed into the mountain which make great areas to illuminate the walls in search of black light rocks

In the dark, scanning for rocks that react to SW Ultra Violet Light is a blast!

Here is a rock responding to SW UV light on the mine dump at the Princess Pat Mine/Just Associates Mine

So, go out and enjoy a day or night at the Shadow Mountain Tungsten District. There are no active claims, there is no ore of worth, it is just you and the coyotes, howling at the moon and looking down at the twinkling scheelite stars…

Rockhound Barstow – Collect Agates, Onyx, Dioptase, Celestite and more in this Mojave Desert Town

UPDATED 3rd Edition Released August 2020 – Get it now direct on a PayPal link, or check it out on Amazon, eBay and Etsy

The Mojave desert is a mineralogically rich area. One small town of less than 30,000 people serves as a great jumping off point for dozens of fantastic collecting sites. Many of these locations are Southern California classics, found in field guides dating to the early 1940’s and surprisingly, still producing to this day. The Cady Mountains are an endless source of material. You can be sure that enough time spent in the loving folds of the Cady mountains will reveal some mind blowing treasures to the lapidarist.

Top Notch Agate being cut into slabs. The Cady Mountains produce beautiful treasures you’ll love working with!

A sampling of cabochons made from material found in the Cady and Alvord Mountains

Just a few miles outside of Barstow you hit the Calico Mountains with a vast silver district, an amazing series of borate deposits, celestite for days, tons and tons of fine selenite and ample supplies of petrified palm root just pouring out of the hills…and silver lace onyx and calcite concretions that can have celestite and quartz replaced spiders and flies inside! That is just the things you can find in a small mountain range just four miles north of highway 15!

Polished Celestite from one of the many celestite deposits found along with the Borates of the Calico Mountains

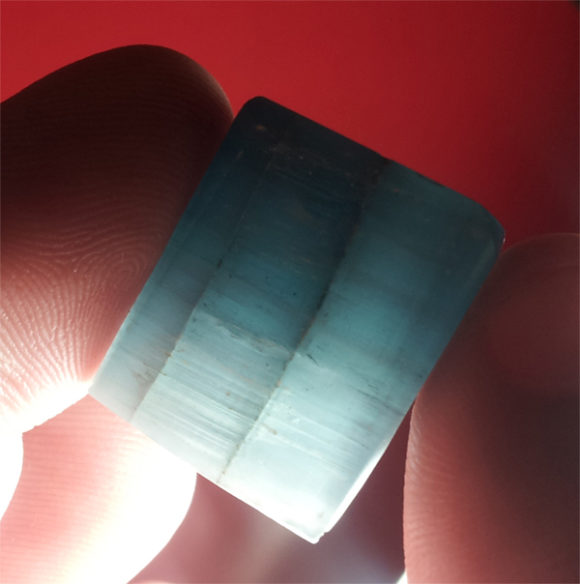

Gem crystal clusters of Colemanite are found in the Calico Mountains, ready to come home with you!

Colemanite glows bright in Short Wave Ultra Violet Light, like MANY of the minerals found in the area.

One of the reasons Barstow is such a great starting point for rockhounding in this area is the prime location. Just 2 hours north-east of Los Angeles and 2 hours south-west of Las Vegas, this town has most everything you need for traveling in this area. Gas, groceries, hotels, restaurants, even the Diamond Pacific Rock Shop, attached to the Diamond Pacific Lapidary Equipment factory. Emergency services, like tire and vehicle repair can be found in Barstow so that even in the worst of conditions, there is somewhere “local” to take care of any problems. Convenience is what Barstow provides and there is no reason why that is not a good thing!

Order it on Amazon, or Buy it for Kindle eBook Readers

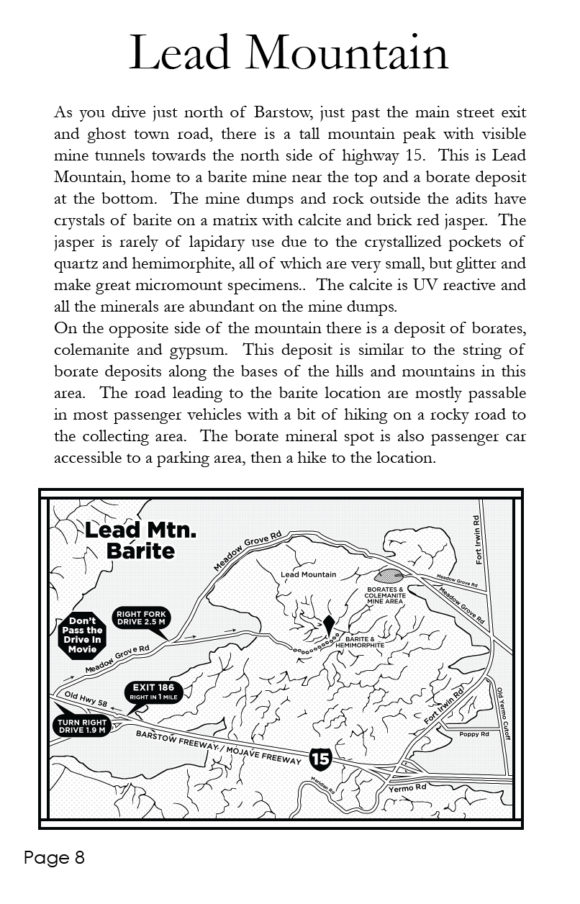

Who better to write and produce this Barstow rockhound field guide than the field trip leaders, Justin and Brandy Zzyzx – locals to the area and avid rockhounds, each of the locations in Rockhounding Barstow have been visited by Justin and Brandy. Justin wrote the text and Brandy designed the maps, as you can see in the sample below.

Sample page from the Rockhound Barstow Field Guide – Lead Mountain, just a couple miles from highway 15, a great place to visit and collect colorful crystals!

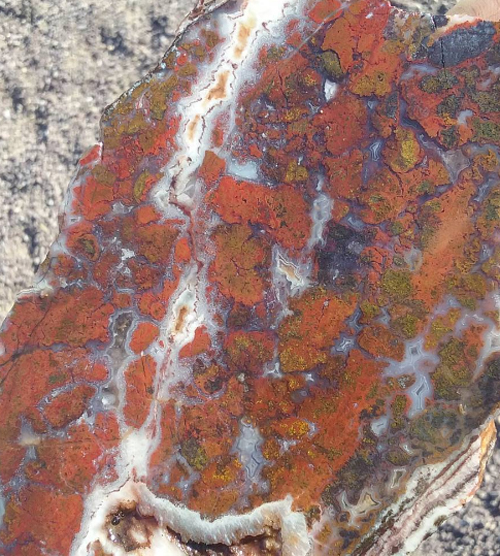

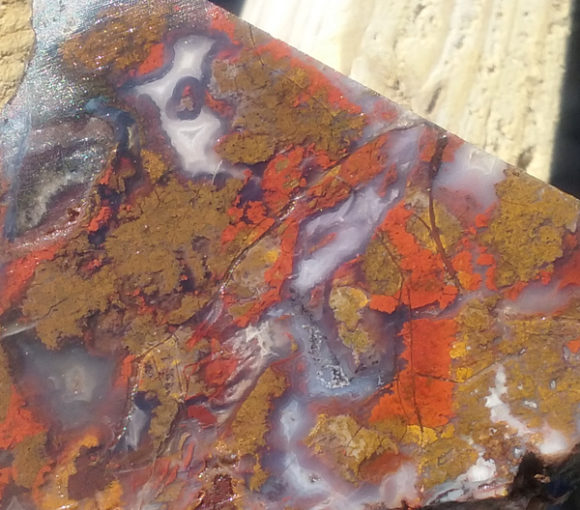

Many of the locations have been written about before, while some of them are being published in this field guide for the very first time. One of the locations that is very exciting is the North Cady Mountain collecting, including the Top Notch claim, prospected by Bill Depue and John Pickett, of Diamond Pacific. This spot has been producing some really lovely material, bright red, golden siderite, fortification and banding of clear and lavender agate. Oh, a day collecting here just can not be beat! You are going to get directions to this very spot and over 30 more locations, just waiting for you to come visit.

Bright Red and Golden Top Notch Agate from the North Cady Mountains, featured in the Rockhound Barstow Field Guide

Siderite is not a common inclusion in agates so it is a welcome site to see this material, rich with gold and red along with beautiful gel agate from the North Cady Mountains

Another interesting feature is the interactive rockhound map provided in the guide. Simply type in the website address and on your phone google maps will open up and you’ll be provided with a pinpointed map featuring all the locations in the book PLUS additional locations, each of them showing you EXACTLY where to collect. Most of the locations in the books will have cell phone service, allowing you to use the interactive google map as a guided satellite directly to the collecting location. Truly a first in terms of mineral collecting field guides!

This fun “Nickel Quartz” comes from the North Calico Mountains Nickel Quartz, Wollastonite, Garnet, and so much more await you, with new locations added occasionally.

By now I’m sure you are chomping at the bit to find out how to get your copy of this booklet. This digest sized field guide, with a color cover, color photographs of what you can expect to find, over 20 collecting locations, all this can be yours for $14.99 plus shipping and handling! That’s right, just $14.99 plus shipping gets you a fountain of information, right at your fingertips!

Simply use PayPal to order directly by Credit Card or your PayPal account or purchase a copy from Amazon, Etsy or eBay.

The abundant Gypsum/Selenite in the Calico Mountains is great for tumbling, polishing, carving and collecting. We use it as a water softener.

The Lavic Sidling Jasper location is not just limited to the classic areas, but also spilling out to the West and North of Pisgah Crater, as you’ll see in the Rockhounding Barstow Booklet

Chalcedony Roses are very abundant out in the Mojave Desert

Collecting by Air – AirMindat takes to the Skies to Collect in Arizona

What do you do when you’re in Tucson at the Gem and Mineral Show on the Friday, when the show is full of school children and you really don’t want to have to be there dealing with them all? Simple. You go collecting. But you need to be back at the show by mid-afternoon? No problem. Let’s hire a helicopter!

The Crew loading into the helicopter in search of Arizona treasures

At the TGMS show in 2009, several of the regulars from the mindat.org online chat room got together to organize just such a trip. The late Roy Lee was the leader of this trip, which we were hoping to make an annual event. Sadly he died just one year later, so this has remained so far the only mindat.org helicopter collecting trip.

We boarded the helicopter at Tucson Airport, after some concerns that too many of us were carrying extra weight. And I’m not talking about hand tools. But, the helicopter made it into the sky and we started our flight towards the Catalina Mountains – flying directly over the Davis Monthan Air Force Base and the “boneyard” where all the retired US military aircraft are stored. It was quite alarming to be flying over the main runway as a C-130 transport was making it’s final descent, seemingly flying straight at us at one point. Having survived our encounter with the US Air Force, we headed off towards our first destination – the Grand Reef Mine.

Mike Rumsey collecting specimens without the worry of washed out roads, boulders or rock slides!

This mine is notoriously difficult to access, with no nearby access roads. So the luxury of being able to fly right up to it and practically land on it was the stuff that mineral dreams are made of. The Grand Reef Mine is famous for linarite and other rare lead/copper secondary minerals. We spent about 90 minutes exploring the locality, collecting on the extensive dumps and admiring the scenery. Everyone in the party found decent specimens.

But what’s better than flying by helicopter to a great mineral locality before lunchtime? Flying to a second – so after we’d finished at the Grand Reef mine, we headed off again to the Table Mountain Mine – which is well known for dioptase crystals. The helicopter made an impressive landing on an exposed ledge (which happened to be made out of glassy slag from the smelters), and we again disembarked and wandered up to the tips to collect.

We all found nice dioptase specimens, but Jim Beam found a fabulous little ‘christmas tree’ of dioptase crystals, and between us we found specimens of conichalcite with possible austinite and duftite. Some samples appear to have minerals previously unreported from the locality, and once they are confirmed they will be reported on mindat.org.

Jim Bean shows off his little christmas tree shaped dioptase cluster collected at the Table Mountain Mine

Finally, we boarded the helicopter for the flight back to Tucson Airport and a short drive back to the Convention center, and we were back in the show almost as the last of the school buses full of kids was departing.

Editor Note – Yes, you can get to these locations, with a helicopter, or a lot of hiking. This article was originally published in The-Vug.com Quarterly Magazine, Vol 4, Number 3. You can get the reprinted book on Amazon, or directly from the publisher on MineralMagazines.com

Pistachios and Minerals – How are they linked?

Minerals have long been used in farming. In the past, different abundances of minerals naturally occuring in nature would influence the local crops. Today, many of those conditions can be supplimented with the addition or subtraction of minerals and elements in the soil.

During the author’s years of growing and harvesting pistachios, the link between raw minerals and the final bagged nuts could be visualized.

Pistachio trees are either male or female. You can graft the two together and have one hermaphroditic tree, for the most part, they are separate and do different things.

The female tree has big broad leaves and branches that have lots of curves and style. The male tree has very thin leaves and sharp pointed branches that have sharp, straight, shoots. The female tree is the one that bears nuts, the male tree is responsible for the pollination. They are wind pollinated, so the timing has to be perfect every year during pollination.

The first mineral we mine and use is raw gypsum/selenite. Just a few miles away from our orchard, we have extensive deposits of raw gypsum, which we then water tumble in a giant 50 pound vibrating tumbler. The “waste” water is a large part of what we need for the grove. Fertilizer for the tree including pistachio wood ash, steer manure, a rich compost and tea, plus, crushed gypsum, all watered down with our waste water from the gypsum tumbling.

Mining Gypsum to use as a soil irrigation aid

Pistachio wood trimmings are used for roasting and fertilizer, resulting in a beautiful cycle of nature and renewal.

Gypsum has a wonderful effect on soil, creating a path way for water to seep deeper into the ground. This is especially useful for this climate as the soil around the trees needs to soak in the water rapidly to the trees, rather than evaporating away from the top of the soil.

The larger pieces of gypsum were sold as tumbled stones by us at mineral shows.

There are two important times in the pistachios tree’s lives every year. In the beginning of spring, which is around March, the branches start to bud.

Female Pistachio Tree Starting to Bud

Boron, from crushed Borax crystals, and Zinc, are applied to the buds on the female pistachio tree just as they start to bud.

During this time, pollination is right around the corner, but first, they need a treatment of minerals to help them through the year. A mixture of Borax and Zinc are prepared and sprayed onto the tree’s branches, in order to do two things. The Borax, which we would mine in Searles’ Lake every October, makes the hard shell form thinner, which allows the pistachio seed to break open the shell while on the tree. You want this to happen, as the shell does not open any further after harvest without additional mechanical processing.

This is a developing pistachio, before it grows the thick brown shell you are familiar with. The Boron helps to keep the nut wall from being too thick, which results in more split nuts during harvest.

The Zinc allows the stems and seeds to hold fast onto the tree, which is very important because the winds in this part of the world can be devastating to an non zinc treated tree, dropping all the blooms and seeds onto the ground, resulting in a loss of pistachios.

These tiny pollinated buds are now hanging on tight, so they can develop into full fledged pistachio seeds.

At the end of October and beginning of November, the trees are harvested. Most orchards are harvested by a nut collecting tractor, some smaller orchards, like ours, are best harvested by hand. With a dozen people armed with trimming knives and buckets, a couple hundred trees can be done in a few days. We separate the nuts from the stems by rolling them around on a large tarp, where the stems start to float to the top of the pile, then, scoop up the pistachios, put them in an industrial peeler which removes the fleshy coating, then float the nuts in a vat of water. The empty nuts float to the top and the ones with nuts sink to the bottom. They are then air dried and roasted with pistachio wood to fuel our ash needs for the following year.

Natural Salt Crystals from Trona California

The end result?

Lightly salted, lightly roasted, pistachio seeds in shell

Now you know what minerals are used in production of the delicious salty snacks you enjoy, hopefully, on the way to a rockhounding adventure!

A Tale of Two Cities – New Mineral Shops in Los Angeles and New York City

Two new mineral shops have opened up on both sides of the continent, in two of the most heavily occupied cities in America. Rock shops are great places to add new beautiful crystals to your collecting, but also to gain knowledge and information. It is certainly helpful to know what minerals look like when you are gearing up for a rock hunt!

In the Los Angeles area, we have a beautiful boutique of crystals in FasanaRock, located near the corner of Foothill Blvd and Myrtle Ave in the foothill city of Monrovia, just a few miles East of Pasadena. FasanaRock is the result of Christina and John Fasana, producing one of the most beautifully designed boutique rock shop! In FasanaRock you will find amazingly colorful and inexpensive tumbled stones from around the world, beautiful and colorful polished crystals, well selected and diverse crystallized minerals, raw crystals and all sorts of educational and decorative items of the natural sciences.

Sulphur Quartz, how Unique! Rub them together and smell ! FasanaRock on 114 South Myrtle Avenue, Monrovia California

How great is this? Colorful furniture contain drawers full of raw crystal goodies! You can find all sorts of colorful additions to any collecting here!

The wooden trays are the perfect way to offer this beautiful selection of tumbled stones!

John Fasana has worked for Rock Currier and Jewel Tunnel Imports for decades, making his knowledge of stones known in the fine selection at the shop.

Great selections of mineral specimens at very fair prices!

Christina Fasana has outdone herself with the store decor, incorporating thoughtful and functional design elements into the presentation of the stones. Along with their family, the Fasana’s have put a lot of heart and soul into this new mineral shop and it is well worth your time to visit it if you are in the Los Angeles Area – Check them out online at their website http://fasanarock.com/ and on Facebook and Instagram

FasanaRock carries Gem Hunt, educational gemstone dig kit – a perfect gift item for christmas!

A store that can provide beautiful minerals and stones at very fair prices, centrally located in the foothill community, FasanaRock is well worth a visit!

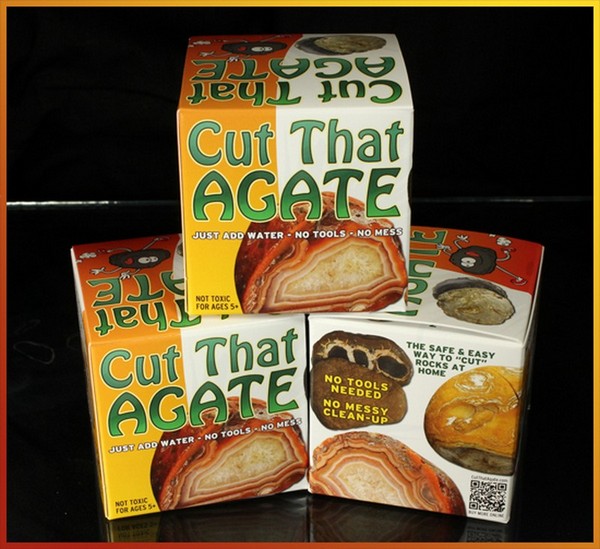

In New York City, an off-shoot of Astro Gallery of Gems, we have Astro West, a store with all the things you know and love about Astro Gallery, with cases of fine minerals, beautiful fossils, and a diverse section devoted to educational natural science kits and interactive crystal features like “crack your own geode” in a sleek looking geode cracking machine.

Astro West – A great place to visit in the Upper West Side New York City

Beautiful Crystals line the cases, ready to be wrapped up and taken home!

The Geode Cracker is fun for all ages and the educational kits are selected for everyone who loves rocks, fossils and natural science!

You can find Astro West online at AstroWest.com and also, find them on facebook at https://www.facebook.com/Astroweststore

It is easy to see why AstroGallery is known for beautiful crystals, all over New York City, now you have two locations to visit!

Check out the website FindARockShop.com for rock shops in your area and as always, thank you for visiting WhereToFindRocks.com!

Dinosaur Aged Amber from the Sayreville New Jersey Clay Pits

Article and Photos by Paul Cyr- eonphader@hotmail.com

New Jersey is no stranger to geological anomaly. Most American rockhounds are familiar with the fluorescent minerals of Franklin and Sterling Hill, and thousands of people from around the globe have graced their collection cabinets with prehnite and other traprock minerals of the Watchung mountains, giving a classic “old school” scientific feel to that shelf of the display. New Jersey has also produced its fair share of paleontological specimens, including many holotypes and species completely new to science. Some of the most interesting finds include gem grade amber with insect inclusions from the Sayreville and Cliffwood Beach areas.

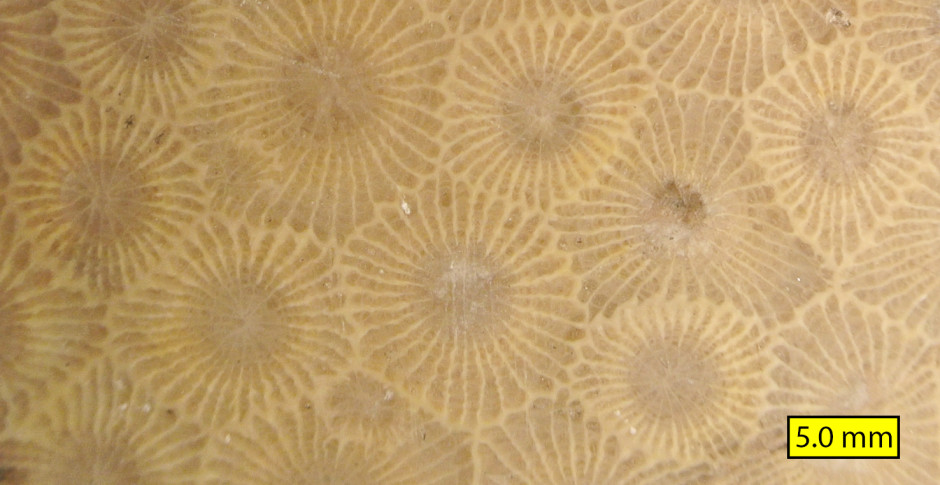

Insect inclusion in a large polished piece of Sayreville amber collected December 3, 1995. FOV 7mm.

The amber occurs within the lignite peat layer above the deep deposits of the South Amboy Fire Clay. The New Jersey amber is the oldest in the Americas with insect inclusions. From this amber, researchers have discovered several new species of ants, including the oldest ones ever documented, giving new branches in the evolutionary line of ants. According to a paper by the American Museum of Natural History researchers, there are a dozen or more amber producing localities in and around Sayreville, but here will will focus on one. In the 1990’s, this locality was monitored by the research department of the AMNH. This study accumulated hundreds of pounds of amber from the Sayreville area, including thousands of specimens with insect inclusions. This was a part of a grand study involving insects included in amber from all over the world. Through this research, many new species of insects were added to taxonomy. Did we mention there is pyrite too?

A nice sized piece of gem amber on clay matrix, with lignite. Fresh harvest.

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly: Amber, Pyrite and Lignite in one specimen. With some careful transport tactics, examples like this can be preserved.

You can find the author Paul, along with the website owner, Justin Zzyzx, at the Edison New Jersey Mineral Show – April 7-9th 2017 It is a CAN NOT MISS Event- Click the Banner and sign up for the mailing list for more information!

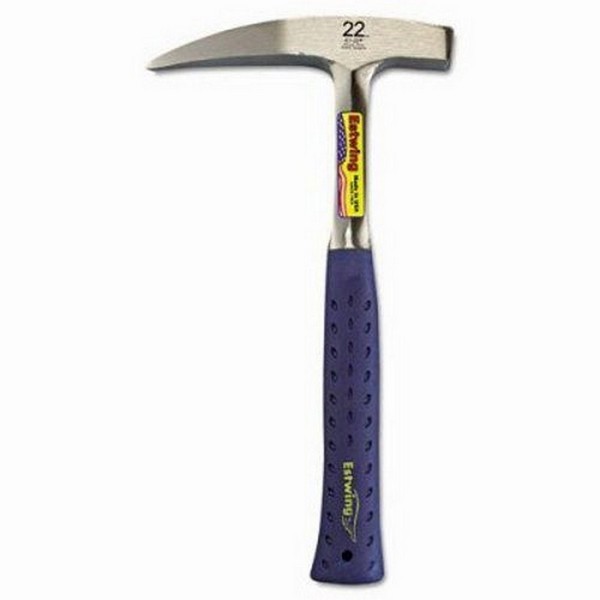

For tools, it is recommended to bring various shovels, picks, small metal rakes, and other digging and scraping apparatus. The porous, but thick and sandy clay behaves differently depending on how wet it is, so you may want to try a few different tools to figure out what works for you. Bring a small plastic vial or jar to keep your amber isolated and safe.

If you have nothing else, a nearly empty plastic water bottle with a bit of liquid left in it will keep your amber safe, and clean it up a bit too.

Fully prepared, gem grade amber pendant shows off a warm glow in sunlight.

In my experience, most of the pyrite is found on the surface, and appears to form due to the iron and sulfur nucleating in the center of the puddles in the cracked clay mud. The pyrite is mostly unstable, and will quickly lose its luster and begin to disintegrate if special precautions are not taken. The main key is to keep it completely dry. I have heard that putting it in a cool oven can help remove all moisture. I have used 3-in1 oil to give them a day dip, and take them out to dry. After the pyrite nodule is dry, apply a few layers of spray acrylic. Unfortunately, only a few of my specimens have held up to this point, but they are unique items in our inventory. Some post-pyrite secondaries seem to be found in microcrystals on some of the pyrites as they alter in the weather. Melanterite and jarosite may be present. More research needs to be done on the pyrite alteration at this locality.

No pyrite in the tire, I checked.

The amber can be founded in small rounded grains along the surface. If you are looking for the large pieces with insect inclusions, you’ll have to dig. The lignite layer is a few feet down (I have heard anywhere from 4 to 9 feet subsurface). Lignite is the precursor to coal, and looks almost exactly like burnt wood. When you get down to this level, you are on the right track. In and around the lignite, you should be able to find evidence of amber soon enough. A nice sized piece with an insect inclusion could be the reward for your hard work.

Fresh amber in the field.

Same pile of amber after first cleaning.

Closeup of the amber.

Plant matter within the amber has been found to be in the juniper family. The lignite peat deposits were probably formed by ancient coastal cedar swamps. The age of this amber has been recorded from 90-92 million years old, in the midst of the Cretaceous Period. Amazing that something so fragile can still exist! This is one of, if not the ONLY locality that produces amber from the same time as the dinosaurs. If Jurassic Park was to happen, we would be thanking New Jersey amber for the DNA. Some of the forms are stalactitic, showing evidence of where it dripped from the tree. It is remarkable to find such objects. Some of the amber is opaque and looks like tan to brown wood opal, with similar luster and conchoidal fracture. The amber ranges from a yellow-hued honey color to a rich cherry red, and can also be brown. It is transparent when wet or polished, making for a beautiful finished product when worked. One gentleman has told me that if you have a big and stable enough piece, it can be polished with a toothbrush and toothpaste- but it takes quite a while. I have a specimen he polished this way in my personal collection. It is almost an inch tall and has a distinct and complete winged insect inclusion. It is one of the treasures of my New Jersey collection.

It’s fluorescent. Most of the amber glows brightly in standard longwave UV light.

To get there, plug in Lakeview Drive Sayreville, NJ into your GPS. When you get on this road, you will be in an apartment complex. Keep following to the end of the road, and park in the little cul-de-sac conveniently located at the trail head. The trail may look enticing, but avoid it unless you plan on exploring for possible separate amber pits. On the left side of the path, climb up the hill right next to the parking area and cross the railroad tracks. You’ll come to the other side where there is a trail. Make a left onto the trail, soon the terrain will flatten. Walk a few hundred feet down, and look for a dip in the brush on the right side. It is crude getting in to the pits, and ticks can be plentiful- use caution.

The Railroad to Amber. Cross over here. Beware of trains.

Ramble through the deer trails- a shovel or sifter can act as a shield through the thicket. Out in this stretch of bush you’ll reach the mud pits, dotted with amber and pyrite to the discerning eye. You may want to check a satellite view on Google Earth for a precise look at the field.

You’ve made it. Welcome to the locality.

A happy amber collector enjoying the ancient fruits of the labor.

This locality is known for its aesthetic cracked mud.

For lunch, I recommend White Castle in Parlin- new veggie burgers are delish! Good luck, and email me if you find anything substantial! Paul Cyr- eonphader@hotmail.com – you can also find Paul and his minerals for sale on Facebook – at the Deep Seeded Trading Post

This video will give you a visual idea of what to expect at the location

Collect Amber and Pyrite in Sayreville New Jersey created by Justin Zzyzx in 2005, now hosted on Vimeo.

Again, don’t forget to sign up for the mailing list for this great rock and mineral show in Edison New Jersey, one of the biggest shows in the United States!

Franklin New Jersey, a Mineral Wonderland

Franklin is a town in Northern New Jersey that has been a fixture in the mineral world for well over a century. Our friend Vandall King has been hard at work for several years on an informative book on the subject.

Instead of us rehashing the subject, we want to showcase the four videos that have been produced to talk about the project and the subject. We are sure you’ll want to pick up the book when it is released – until then, enjoy these videos! If you enjoy them, please leave a comment on the videos and give them a thumbs up.

Franklin Video 1

Franklin Video 2

Franklin Video 3

Franklin Video 4

You will be sure to find out when the book is released as we will be certain to tell you here on WhereToFindRocks.com!

Red Jasper and Celestite Geode Specimens found near Hanksville Utah

Every year we look forward to visiting one of the most beautiful places in the world, the San Rafael Swell, a series of sandstone, shale and limestone that has been worn down by erosion by water, air and time.

A group of rain clouds hangs in the air above the dramatic rock formations of the San Rafael Swell

One of the best things is that the collecting locations are fairly close to highway 70, a road we travel every year in order to go back and forth from California to Colorado for the annual Denver Mineral Show, which is taking place as I type this.

For rockhounds and lapidary artists, the bountiful red/yellow jasper found in this area is worth stopping for. The jasper nuggets are found with a bubbly rind, colors caused by iron oxides, accepting a fine polish.

Red and Yellow Jasper with a bubbly rind, found near interstate 70 in central Utah.

Bubbly Red Jasper Rind on a Crystal Filled Geode

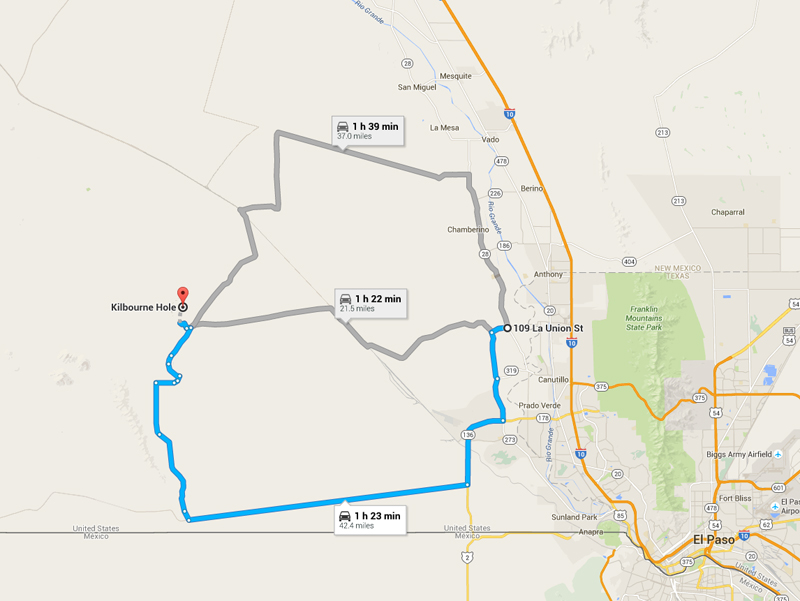

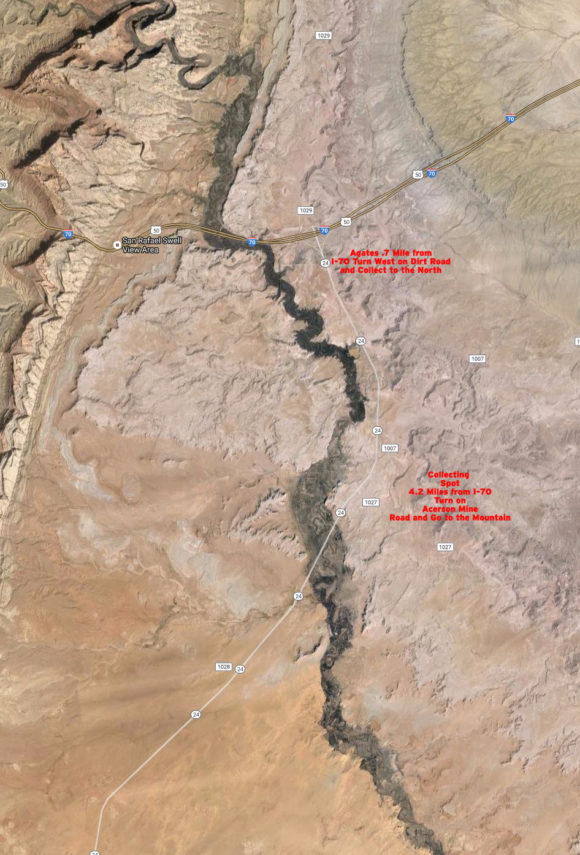

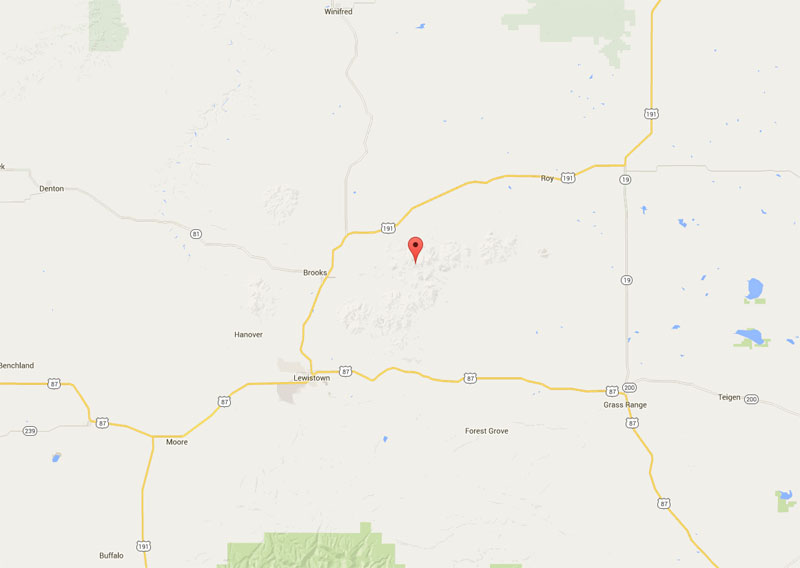

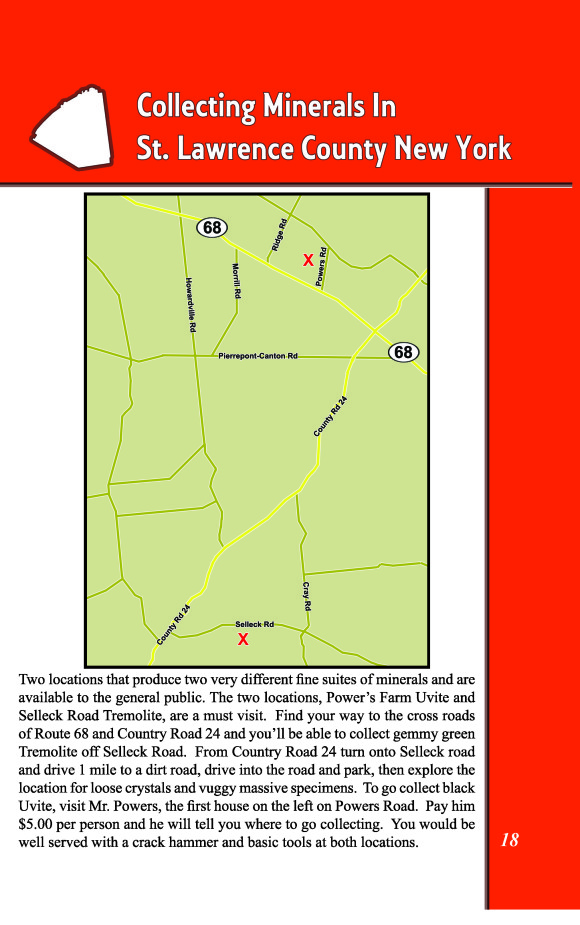

There are several areas to collect jasper, as you can see on this map, the two main areas are directly south of I-70, both accessible with a standard passenger vehicle. The first location is just north of a dirt road you enter heading West, .7 mile from the exit on route 24. The next location is on a dirt road heading east 4.2 miles from I-70, or 3.5 miles from the first dirt road.

Two Jasper locations off highway 24, just south of interstate 70

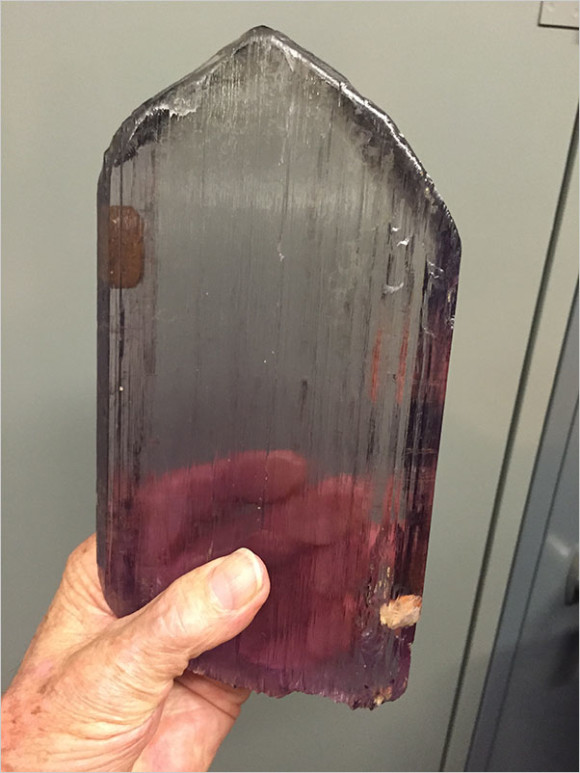

The exciting thing to find while out looking for jasper are thin walled geodes with crystals of celestite, calcite and quartz inside. By gently splitting along the cracks in the walls of the geodes, you can find bright blue crystals of celestite, up to 4.5 cm, along with calcite in various forms and colors and druzy quartz, sometimes with an amethystine color.

Celestite Crystals inside a geode of Red Jasper

Thin blades of Calcite forming on the inside of a red jasper geode

The geodes are created due to the fact that they were originally filled with anhydrite, which then dissolved, mixed along with the marine sediments, giving the proper environment for celestite to form. The celestite in this area used to be mined commercially back when celestite was in demand. Now, there is very little demand for the raw material, which can be sourced very cheaply from sources around the world. The celesite is now mined for mineral specimens, sporadically.

Orange Calcite crystals with Blue Celestite crystals from the Swell

Gray sparkling Quartz in a Jasper Nodule

When looking for these jasper geodes, you can often tell if there are crystals inside by the weight. Be careful not to shake the geodes violently, as loose crystals can smack into the crystals attached on the matrix. You most certainly do not want to smash these geodes open with a hammer, you can typically find a crack or fissure in the wall and pry it open with a screwdriver.

Utah is a beautiful place. This remote, yet, heavily traveled, area of the world, is a perfect reason to stop and stretch your legs! I hope you enjoy a trip to this area at least once in your life!

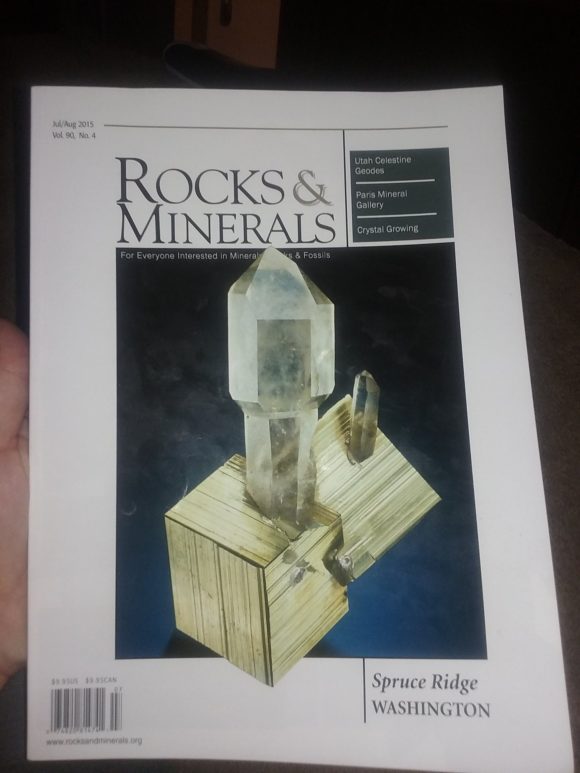

Cover of the Rocks and Minerals issue with a very well written article about the Celestite Geodes of The San Rafael Swell.

We highly suggest this issue of Rocks & Minerals photographed above. Rocks & Minerals is well worth subscribing to, they are one of the best mineral magazines ever printed.

The Springfield Massachusetts Dazzling Mineral Displays!

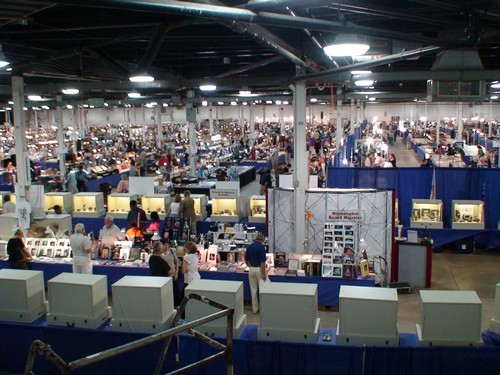

Every year the town of West Springfield plays host to the East Coast Gem and Mineral show by MZ Expos. Each year the show has the finest dealers from all over the united states and the world, bringing to you specimens of colorful minerals, amethysts and fluorites, gold crystals and books and literature about all sorts of mineral topics! Knowledgeable people, free lectures and every year, a featured exhibit with a very special twist.

Overhead shot of the 2007 East Coast Mineral Show in West Springfield, Mass

For many years the East Coast show followed the usual club show format, with a variety of collectors and dealers being invited to display each year. Under those conditions, the quality of displays can be unpredictable and sometimes disappointing. The first year with a special theme was 1998, when Illinois minerals were displayed by Roy Smith, Ross Lillie, and Tom Weisner.

Fredrick Wilda East Coast Mineral Display Case of Rhodochrosite from 2012

The single (or limited) exhibitor theme was viewed as a way to be different from most other shows. It has given visitors a chance to view many private collections that are seldom on display to any extent. Private collectors and museums have enthusiastically participated since the start. The exhibitors seem to enjoy the challenge of displaying, and the chance to share their collections. For the EC staff, it is much easier to coordinate with just one or a few individuals. The “special exhibitor” program has been a win-win situation all around.

MINERAL SHOW EXHIBITORS

Glossy Smithsonite Specimens from the Gail and Jim Spann Collection, on display in 2009

This year features free public lectures by Bob Jones, Peter Megaw and Kevin Downey on a variety of subjects – Admission is $8, you can save $2.00 with this coupon link. The event is at the Better Living Center and runs August 12, 13 and 14. There are nearly 100 dealers to buy from and the Mexican Mineral Collection on display, by Peter Megaw is an amazing chance to see a private collection that will show you beautiful top quality minerals from all around Mexico. The colors, shapes and forms of these classic minerals will astound you! Find out everything you need to know on the MZ Expos website, MZExpos.com

Herb Obodda traveled in the Afghanistan and Pakistan mountains in search for the very finest crystallized minerals found in those rich deposits.

2011 had the Scott Rudolph collection, featuring this AMAZING Rhodochrosite from Colorado

2008 Herb and Monika Obodda Collection

Amethyst Clusters from Mexico from the Artist Frederick Wilda, 2012

2009 Display Case from the Gail and Jim Spann Collection

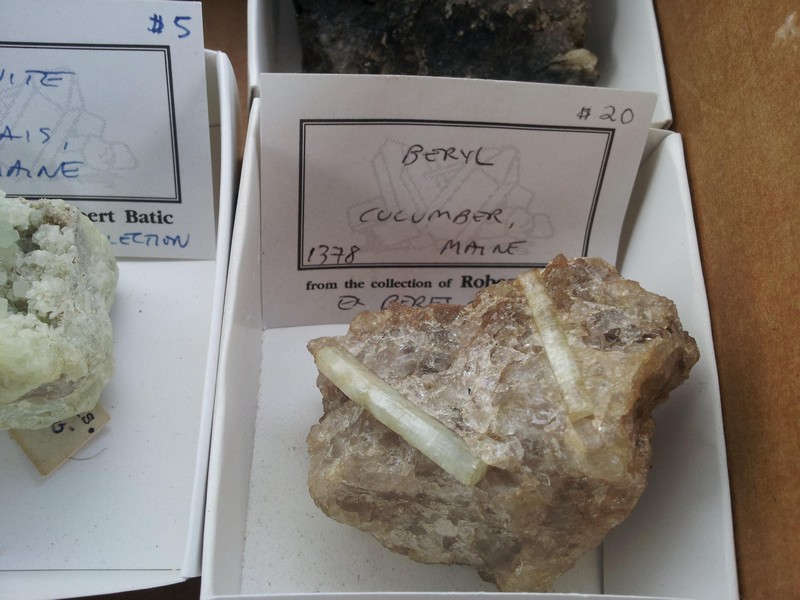

Bill Larson’s collection is rich with history and american classics, like these pegmatite minerals

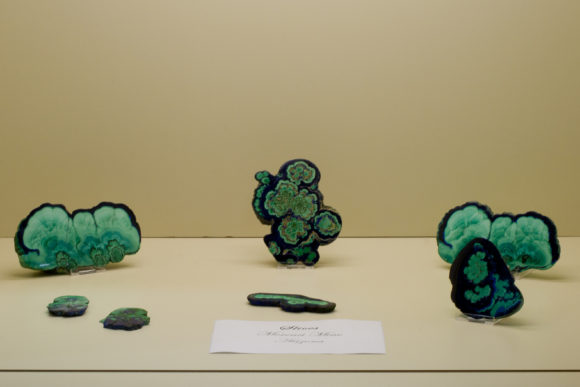

Beautiful Malachite Slices from the American Classics of Bill Larson/Pala display in 2011

Scott Rudolph’s collection from 2011 featuring this beautiful Diopside on Graphite.

Photos by Cindy Rzonca

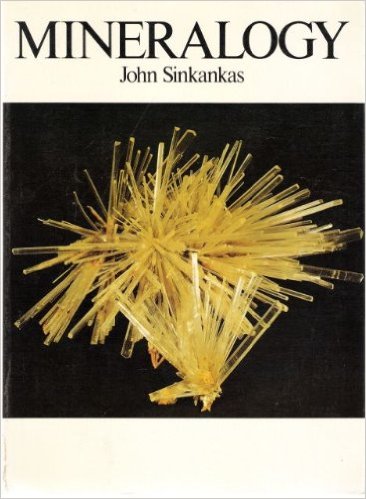

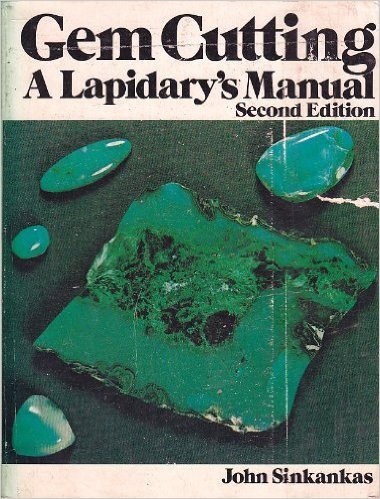

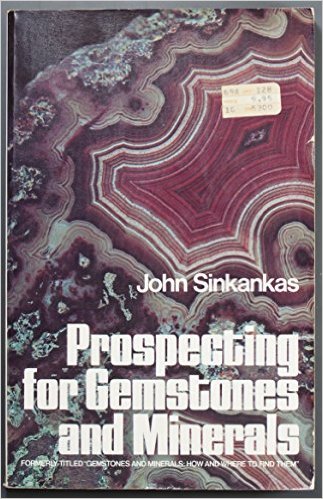

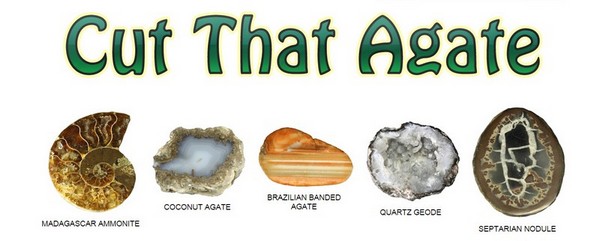

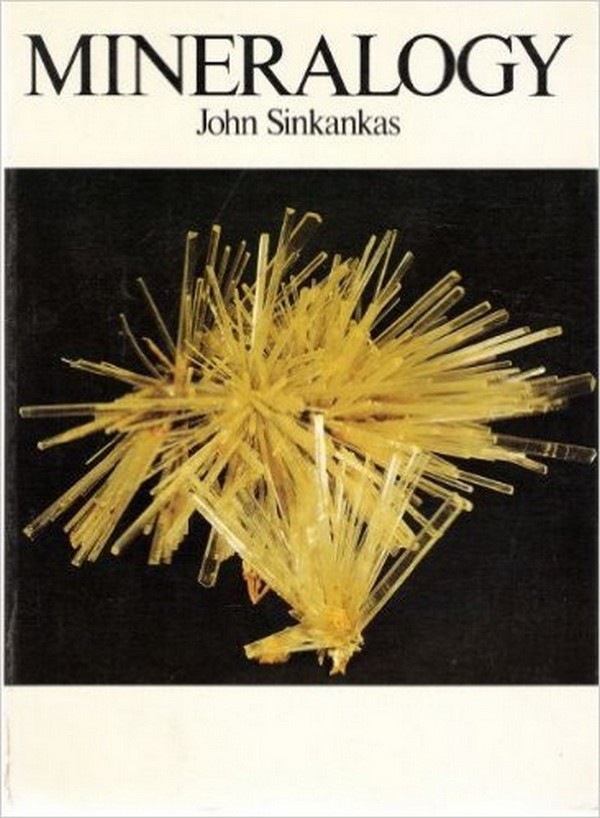

Every mineral collector and rockhound should have these books by John Sinkankas

Rockhounding is a great hobby, rewarding and full of adventure. Few people know that to progress in knowledge about this hobby is easy as can be, it just take a little bit of reading and we have the perfect selection of books to talk about today, ones that will give you a full understanding of minerals.

All of these books were written by Captain John Sinkankas, a well noted and respected author who has a way of explaining things that many thousands of people have enjoyed and understood.

The most important thing about this article is the perception of mineral information, versus the reality. Guidebooks like the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Rocks or the handy Smithsonian Handbook, well, they just do not do a good enough job, in our opinion. Sure, they are colorful and glossy, most starting collectors will have one or the other at some point in their life. However, if you have more than just a passing curiosity about rocks and minerals, there is a better way.

Mineralogy is the #1 book that we recommend to all mineral enthusiasts. The writer, John Sinkankas, has an easy way of explaining how atoms form crystals, and why the crystals different properties make them look different from each other. It is technical mineralogy explained in a way that most anyone can understand. The book can be treated as a college level book on the subject, yet, can be enjoyed casually with chapters devoted to different topics including over 300 photographs and line drawings, this is the must have book for everyone interested in the subject. You can find this book on Amazon and eBay. It was originally published in the 1960’s, any edition is worth owning. You will find it as a “Used” book, it typically retains value as it is a book that all mineral and rock collectors have loved for decades.

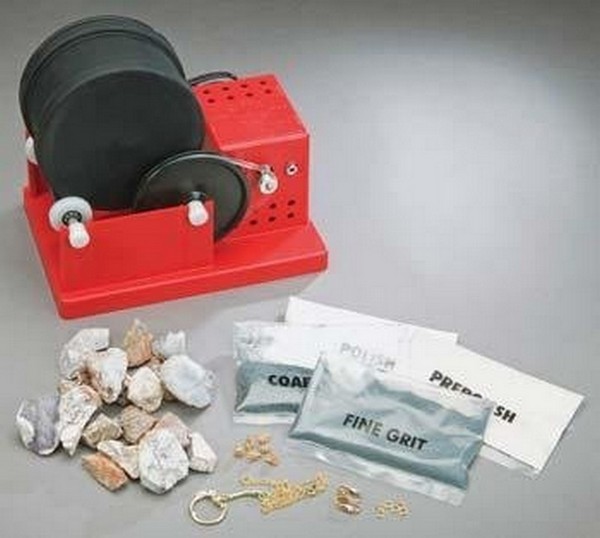

Gem Cutting: A Lapidary’s Manual is John Sinkankas’ perfect tome devoted to all the basics of lapidary. The mystery of most every lapidary art is reveled, along with photographs and drawings to guide you to understanding the complete basics of lapidary arts. In the first chapters you are introduced to sawing, grinding, lapping, sanding, and polishing. Rock drilling is a common question, this book gives you the knowledge on that, plus, all the tumbling, cabbing, faceting, sphere-making, carving and engraving and mosaic and in-lay work information, including tools of the trade, tips on techniques and so much more. When I need to know what polish to use when I’m tumbling stones, I look to this book. This has an amazing wealth of information on this subject. The second edition is the edition we suggest and the big paperback edition is a great addition to any library.

Prospecting for Gemstones and Minerals is a perfect primer to understanding where to find rocks. Deposits are explained, how to find them, what is inside of them, and how you can get crystals out of the ground. This book serves as a primer to all topics on the subject of rockhounding. Over 350 pages of quality information, that, if you were to read, would put you in the ranks of the top collectors.

All three of these books are easy to read and understand, teach you the basics and the nuances of each subject are highlighted and explained. To read and understand these three books is to have a near complete general knowledge on this subject of rock and mineral collecting.

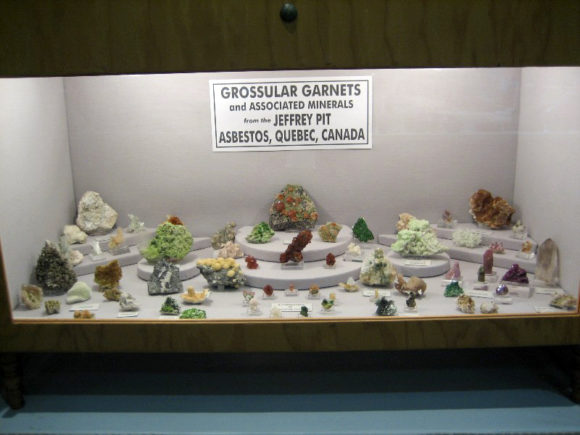

Best Practices Guide to Gem Show Display Case Design

As time goes by and your rock and mineral collection grows, you may start to ask yourself, “What can I do with all these rocks?” Of course you already display them at home and you are constantly showing them to your disinterested friends and family, but have you ever thought about showing your crystals to the public?

Creating a Display for your local rock or gem show is a fun and creative way to share your love of crystals and minerals with others. Most rock clubs love to have their members and other collectors within the community exhibit their gem and mineral collections during their annual rock shows and tail gates.

In my decade plus of working within the rock and gem show world, I have seen, and created a great many rock and mineral display cases… some even winning awards at the Tucson Gem & Mineral Show™. From this experience I present you with Brandy Zzyzx’s Best Practices Guide to Gem Show Display Case Design.

Step 1. Contact Gem Show Display Coordinator for permission to participate

The first step is contact the Display Coordinator for the Gem Show in which you wish to display. For larger mineral and rock Trade shows, this information is often easily found the show’s website, but for smaller, local shows many times this information is not listed on the show’s (or club that is hosting the show’s) website, or they do not even have a website. If there is no Display Coordinator, try to contact the Show Promoter or Show Chair. Or speak to any member of the hosting club that you may know, and they should be able point you in the right direction.

Before being able to exhibit your rocks, you will be asked to fill out 1 or more forms and/or releases. Each club as their own specific rules about cases, liners, and appropriateness for general (non-competitve) displays. More advanced collector’s may wish to compete for display awards that may be given out by the club. These types of displays have additional rules, specifications, and forms. If the club is a member of American Federation Mineral Societies, these competitive display rules and regulations are determined by the federation; making them consistent across all rock and gem shows in the US.

After you have secured a case for the duration of the gem show, and have been given the display case dimensions and the date of the show, it is time to plan exactly what you want to display and how to go about it. Sure you probably already have an idea of what you want to do, but now is the time to finalize those plans.

Step 2. Pick a Theme or Statement of Purpose for your display case

Anyone can throw some rocks in a case, but that doesn’t make it worth looking at. Don’t kid yourself; if you phone it in, everyone who sees it will be able to tell that you didn’t even try. So before you pick out any rocks, ask yourself why you want to put together a display case and your purpose for sharing your collection. The answer to this question will make putting your case together so much easier and aid you in creating a visually appealing display.

What is my purpose for displaying my rocks & minerals?

Answer 1.To showcase my collection of rocks & minerals

What one thinks of as traditional rock and gem show display cases. Usually they are a sampling of collector’s personal rocks and crystals, however they can also be compiled by a group of people or a case presented by museum or school. In some instances the display case may be on a theme, such as minerals all the same size, all specimens from the same locality, or all the same type of mineral. Traditional display cases usually have very little, if any signage except for specimen labels, because the rocks, crystals, or gems are the main focus of the display.

Answer 2.To teach the people about rocks & minerals

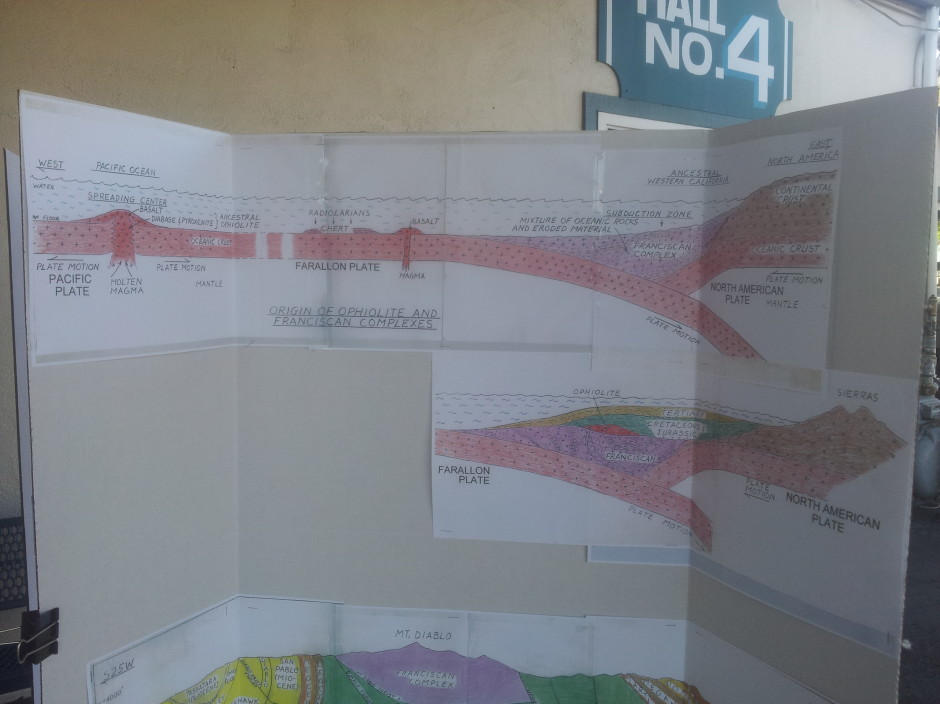

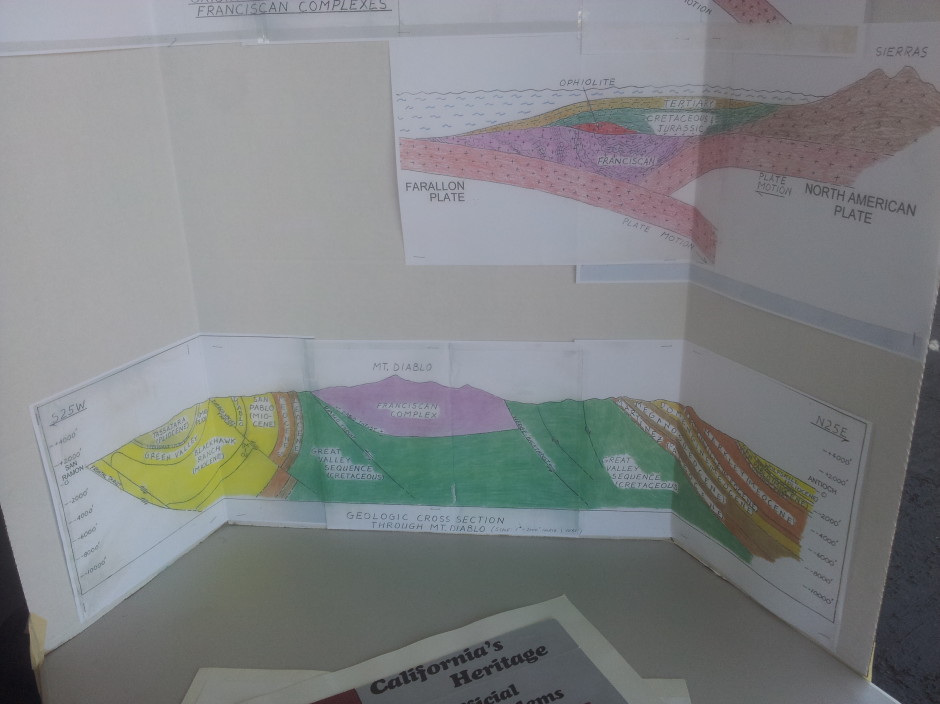

Display cases that are educational in nature are usually submitted for display from schools and museums; however it is not uncommon for companies and advanced mineral collectors to also create informative displays for larger, international gem and trade shows. Sometimes the displays are scientific and technical in nature, often times showcasing more specialized or vocational rock and mineral information.

Another popular example is detailed timeline of the operations of particular locations or discovery history of a specific mineral type. These types of displays usually have many signs, graphs, charts, photos, and labels; sometimes even paragraphs of text to read. Illustrating and educating the viewer about the rocks or minerals is the primary focus of the display; specimens are used to convey the information

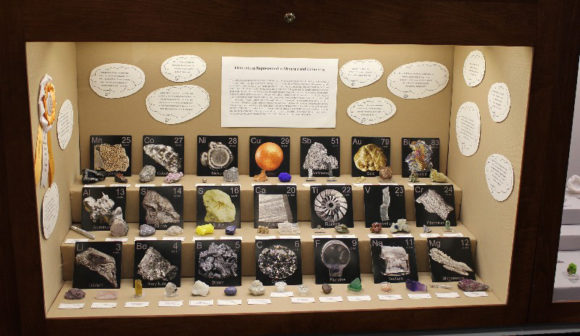

Eye catching display pairs real mineral specimens with printed stand-up pictorial signs representing elements from the periodic table

Answer 3.To share my experiences with rocks & minerals

Display cases that may be related to rocks and minerals, but are actually more about telling a story or relaying a feeling or memory. These types of displays are often very different from the displays around them; they showcase the achievements or thoughts of the humans involved as the main focus.

Sharing your hobby or craft in a gem show display case is a great way to get both exposure and feedback on your creations.

The rocks and minerals provide a social construct for the sharing of mutual interests and experiences. Immediately recognizable, most commonly seen examples are displays of someone’s art, craft, or other creative endeavors, and what I call meta-displays. This is a display inside a display.

Creating a Meta-Display, or “display within in a display” is a clever way to commemorate a past achievement or memory.

For instance, the specimens and awards from a winning display case 25+ years ago recreated now. Memorial cases of photos and specimens of a departed collector or of a closed location are other ways to immortalize stories and experiences from our community’s collective past. These may be the hardest type of display to execute due to their personal nature. Although sometimes seen as cheesy, these cases are quite important; often times the stories and history of our collective past is otherwise forgotten if not shared.

A memorial display is a meaningful way to reintroduce that younger generation of collectors to communities members that have passed away.

A great display may contain elements from multiple categories, but as a personal guide, I like to narrow down my themes. This will not only make it easier for you to decide what specimens to include, but will help the viewer be able to understand and appreciate your case quickly in a noisy/busy gem show environment.

Example: If your case is a display of mixed minerals from your personal collection, maybe choose specimens that are all the same size. Or conversely, if displaying all the same mineral from one location; showcase the different sizes, shapes, and color variations that can be found.

Choosing a theme or purpose for your display case creates a guideline to work within as you gather specimens and other elements. As you assemble your display, choose only items that will help further your purpose and stay within your desired theme.

Step 3. Plan and execute the actual design and presentation of your display case

Use of Size & Balance: A display case is essentially a box that you are filling. The very best, and most visually appealing displays are ones that utilize all 3 dimensions; length, width, and height. In order to take full advantage of the entire volume of a display case; risers, pedestals, and other display accessories are used to not only provide height, but to assist in the viewing of all specimens equally; this is especially necessary if the specimens are small or if there are many of them.

Combinations of risers in various sizes and shapes ensure that all specimens can be viewed equally well.

For mixed size mineral cases, place larger specimens in the back or on the sides of the display and alternate the spacing between rows to ensure optimal viewing of each specimen.

In certain displays signs and photos can be used to add height to an otherwise empty display; either on easels or by attaching them to the back of the case insert.

Signage can provide information to the viewer and ad additional height and interest to the overall case design.

Use of Color & Contrast: While many rock shows will provide you with pre-covered fabric liners for the inside of your display case, most people prefer to provide their own. This gives the exhibitor the ability to choose a color that will showcase their rocks or minerals in their very best light. For instance, if you are displaying a case of white or clear specimens you would probably want to choose a dark colored background material, as to provide visual contrast for the viewer. In some cases, you might want to use a monochromatic color scheme, like using a pink background for a case of hot pink rhodochrosite specimens.

When considering color, also remember that risers and stands are made of materials that also have distinct colors. Styrofoam is mostly white, display stands usually are clear or black plastic, and labels and signs are usually predominately white. All these elements will change how your specimens and your overall display is perceived by viewers.

Generally, neutral or natural colors are preferred for backgrounds, stands, and other non-specimen display items. Creative but tasteful use of color can enhance your display in some instances, but remember, “less is more.”

A monochromatic pink color scheme is being used as a means to draw attention to breast cancer awareness. Pairing pink specimens with black risers and clear bases creates a bold contrast that draws the veiwer’s attention.

Use of Tools & Materials: Even though just about anything can be used in the creating of a mineral display case, there are some materials and methods that are tried and true. Back and side case inserts are usually cardboard, foam core, or wood cut to size and covered in fabric that is secured in place by duct or masking tape. The best fabric to use is something not too stretchy or loose knit, and that is forgiving to marks and stains. Cotton, Blends, Suede, Canvas, Muslin, and Flannel are all materials I have seen used successfully. When covering your own case inserts, iron your fabric beforehand to remove creases before securing it to the background board.

Stands and risers can be purchased pre-fabricated or DIY concepts of your own design. Materials used for risers are wood, plastic, Styrofoam, Foam core, or cardboard. Pre-fabricated risers and pedestals are often clear, white or black, but DIY risers made of foam or wood could be easily painted or covered with fabric to enhance the display or to create a custom effect. Those with special tools, skills, or talents could employ any number plastic, metal, polymer, or 3d printed bases, risers or stands to give their display a unique style or feeling.

Stands and risers can be purchased pre-fabricated or DIY concepts of your own design. Materials used for risers are wood, plastic, Styrofoam, Foam core, or cardboard. Pre-fabricated risers and pedestals are often clear, white or black, but DIY risers made of foam or wood could be easily painted or covered with fabric to enhance the display or to create a custom effect. Those with special tools, skills, or talents could employ any number plastic, metal, polymer, or 3d printed bases, risers or stands to give their display a unique style or feeling.

Small minerals and crystals are mounted on stands. These stands usually are foam or Lucite, with the specimen mounted with mineral tack, white glue, or hot glue. Before displaying, take into consideration what type of lighting will be used in the display case. Many smaller clubs still use hot burning display lights, so a specimen mounted to a stand with mineral tack my fall over under the heat of a display lamp. This is also true for signs and photos attached to backgrounds. For this situation, I would recommend high melting temperature hot glue to mount the specimens and a very sticky tape or possibly tacks for the pictures and signs (depending what the background material is.)

Making sure the viewer can see all specimens equally is especially important when displaying many similar sized specimens within a large display case.

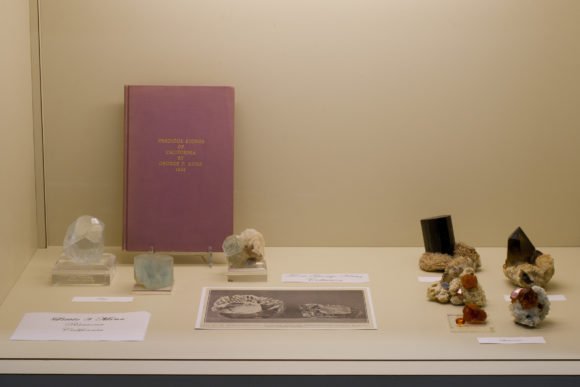

A combination of wide risers and framed documents is used to fill up the entire volume of this display case.

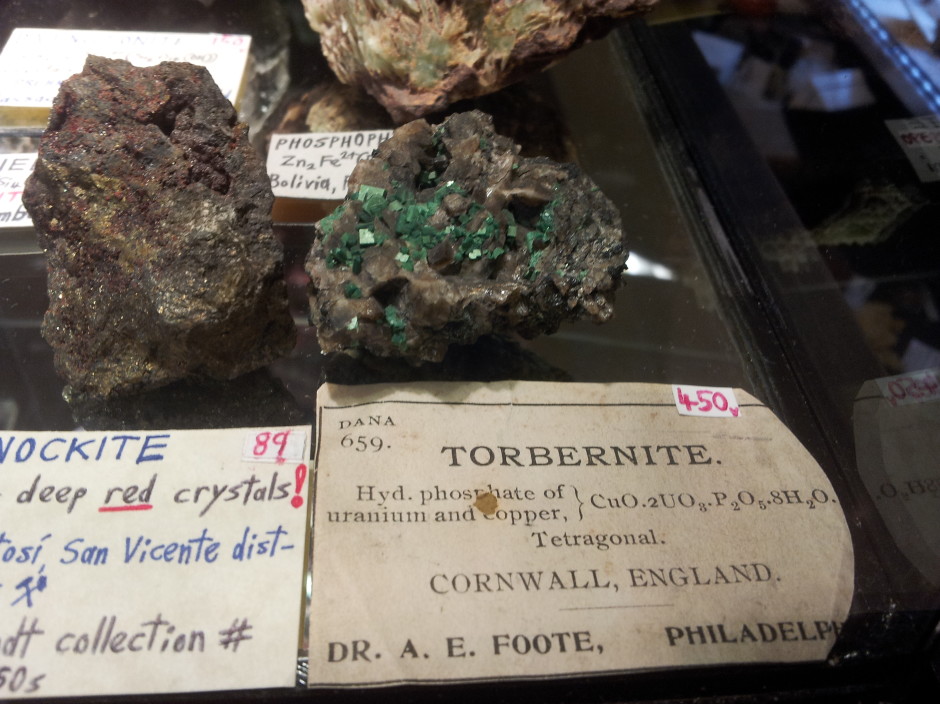

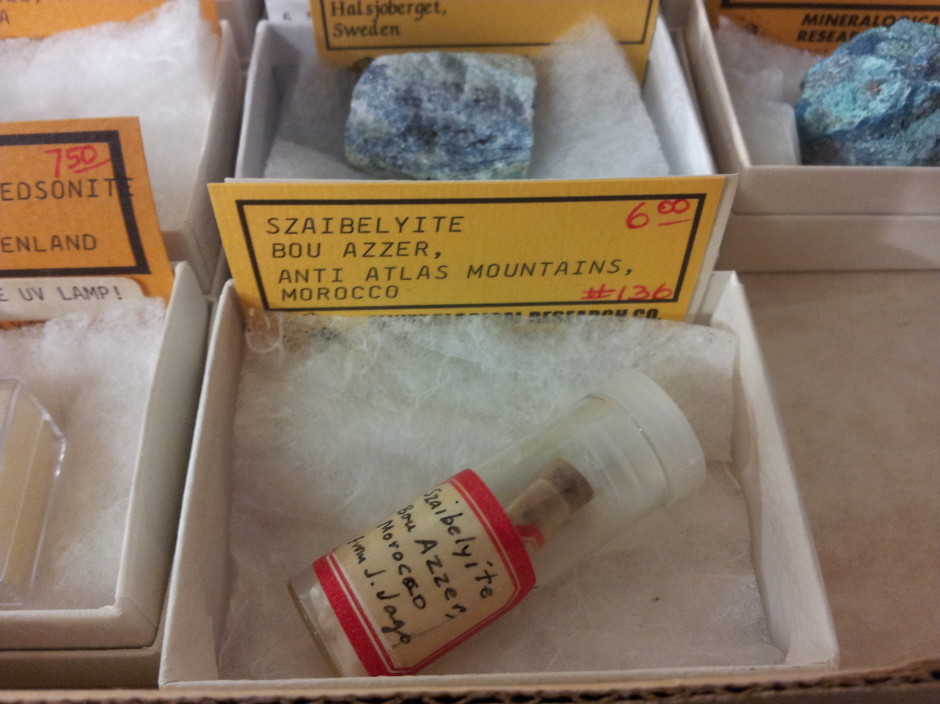

The inclusion of other types of ephemera as an accompaniment to the rocks and minerals is a way to help create interest, add height or to carry a theme. This could be documents, antiques, labels, models, optical equipment, plaques, souvenirs, etc.

Tasteful and well thought out choice of non-mineral items can be used to reinforce your display theme or idea.

Step 4. Make sure your rocks and minerals are display ready

Orientation, Cleaning, Mounting, and Labeling a mineral or rock effectively can be confusing for many novice exhibitors. The correct way can be largely subjective and often times shape or size can create challenges for even a seasoned collector.

Orientation – Always display full, terminated crystals facing the viewer. Broken crystals should face toward the back or bottom when all possible. If you are unsure what your crystal should look like, look up photos.

Cleaning – Clean any dust or dirt from your minerals and rocks prior to displaying them. Depending on the nature of the dirt/mineral cleaning could be a spray of compressed air, a soft paint brush, soap, and water, or scrub with a toothbrush.

Mounting – Mount small specimens on stands or bases securely using an appropriate adhesive. Test under shaking and heat to ensure effectiveness of the mount.

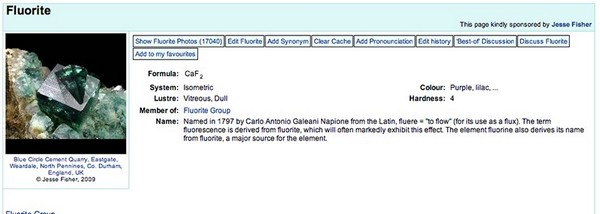

Labeling – Look up the localities of all minerals online (I recommend Mindat.org) or in reference books to ensure that you have the correct information and spelling. Use a clean, simple, font that is easy to read, and consistent throughout your display. Cut your labels out carefully and neatly with either a paper trimmer or scissors. If colored paper or text is used, make sure that the information is easy to read, that the contrast isn’t too drastic, and that it doesn’t detract from the overall display.

Display of cut and rough stones requires precise placement of the cut gemstones in relation to their corresponding natural crystal counterparts.

Step 5. Practice, Prepare, Pack, Present

Pay attention to the details, this is what will make or break the successful execution of your display.

- Double check the spelling and grammar on all labels and signs.

- Make sure dirt, dust, stains, or hair is removed from all fabric.

- Check all mountings for stability and adhesion.

- Do a practice set-up of your display case and see if all your minerals are clearly visible.

- Once you have decided on a final layout, take a photo of your practice display to use as a reference for real display day.

- Pack everything up backward as to how you will unpack it; pack items in the back row first, ending with the first row last.

Pack your minerals securely for transportation to the show location. Place backing boards, fabric covered inserts, risers, and other items inside bags or boxes to protect them from damage or dirt during transport. Transport signs and labels in a folder or envelope to prevent wrinkling, creasing, or other damage.

Usually display cases are set up the day before a gem show opens. You will be given instructions as to the date, time, and procedure beforehand; save these on your phone or print them out and bring them with you. Be prompt, wear your name tag if asked, follow any parking instructions, and try to finish setting up your display case in a timely fashion.

This exhibitor decided to forgo a back insert altogether and attach the signage directly to the wood of the case. Sometimes you are forced to make onsite alterations to your idea, so bring your supplies.

Bring all tools and accessories you may need to set up your display case; you cannot be sure what will be available to you. Here is an example list of items to bring along on set-up day.

- Hot glue and glue gun

- Mineral tack

- Scissors

- Hobby knife

- Masking Tape

- Duct Tape

- Iron

- Lint roller

- Thumbtacks

- Glass Cleaner

- Paper Towels

- Ruler

- Spare Stands and bases

- Tweezers or forceps

- Extension Cord

Most importantly, have fun and create a display that makes you happy. By deciding to participate in the sharing of your rocks and minerals with other members of the rockhound community, you are helping to keep our rock and gem shows interesting and diverse. All the pointers and examples in this guide are presented to help you through the process of creating your own, unique display cases with less trial and error. For more information on display cases, visit your local gem, mineral, rock or lapidary club.

Petrified Wood Near Colorado Springs – Pairing Old Information with New technology!

Rockhounding is a hobby that anyone can pick up, with very little in the way of costs besides time and transportation. Colorado is a wonderland of mountains, forests and rocks. Petrified wood is always fun to find and in many places around Colorado, abundant. Let’s show you a fun way to research locations from old data sources.

Available on eBay, Amazon, and at mineral shows across the nation, old magazines are full of rockhounding information!

By old data sources, we mean, old magazines, books and pamphlets about collecting minerals. Rockhounding was very popular in the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s, which lead to the production of all sorts of printed material for rockhounds and lapidary enthusiasts. Today, even if rockhounding was nearly as popular as before, the internet is the land of independent media, yet, the information from those sources is so niche, it takes people specialized in transferring that information over to bring it to light, instead of waiting around for others to research and publish, you can take charge and research many things from your computer, using information from sources like this one, The August 1967 edition of “Gems and Minerals”.

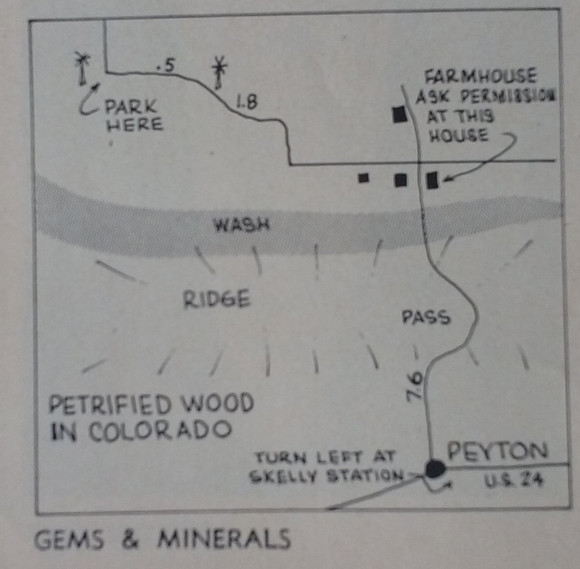

The article, entitled “Petrified Wood in Eastern Colorado” by Eugene M. Beason, describes a large wash where petrified wood is plentiful. Due to the nature of these alluvial rock deposits, every year new material is churned up by erosion by wind and rain, so if there was ample material in 1967, there would be ample material in 2016. Property ownership is always evolving and changing and must be verified by any possible explorer.

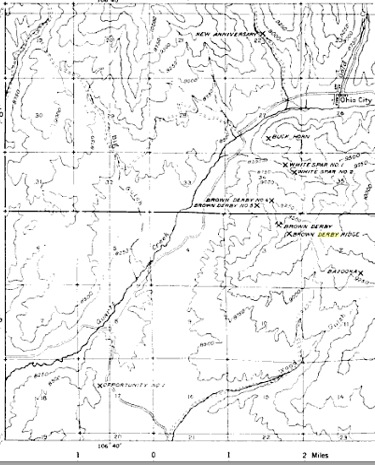

Original Map to the Petrified Wood Collecting area in the 1967 Gems and Minerals article.

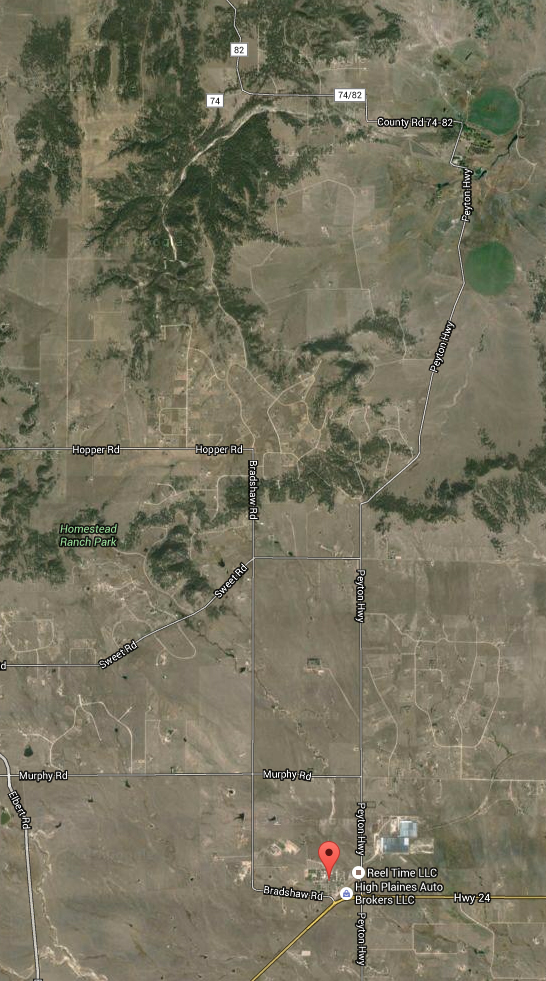

Many things have changed since this article was printed, nearly 50 years later. Instead of the turn being the “Skelly Station”, we can see the map is pointing to “Peyton Highway”, which runs north to go over a mountain pass and turns hard left (west) on “County Road 74/82”, which parallels the wash that is talked about in the article. I do not think there is any need to stop at the farmhouse listed in the article to ask for permission, as the ranch land gave way many years ago to the need for housing, as the populations in nearby Denver and Colorado Springs swelled, so did the growth out into the nearby countryside. 50 years ago there were just cows and a couple windmills, now there are hundreds of houses dotting the landscape. The issue is that the property in Colorado has two things going against it – Waterways can be included in property lines and property does not have to be POSTED to give first refusal to entry, as in most states in America.

This map shows the area as shown in the illustrated map above.

As we searched google for information on this location, the terms “Peyton Petrified Wood” were coming up nearly blank. We did find an entry for it on Mindat.org, but it did not show anything directly from this location. Additionally, PeaktoPeak, a well known website for Colorado collecting, has a bit about petrified wood from that general area. Digging through field guides to Colorado, we could not find this location listed, could it have been one of the locations that simply slipped through an information hole, getting a two page article and then just…relegated to maybe popping up in a mention in a local club newsletter. It IS possible to contact the property owner, Tim Richardson, at timothy.k.richardson@gmail.com for guided tours of the petrified wood deposits.

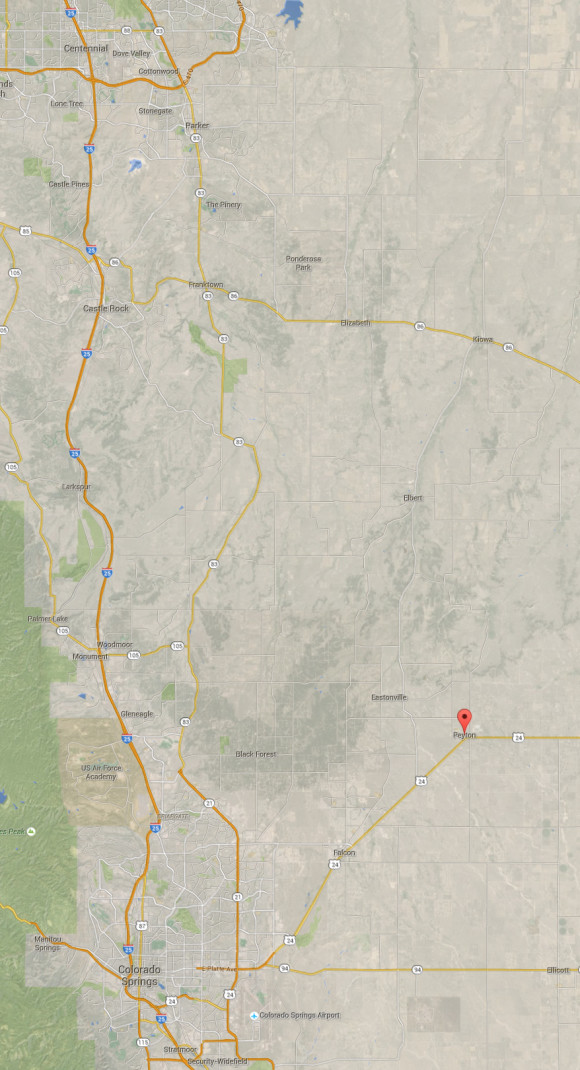

as you can see, Peyton is not a far drive from Denver or Colorado Springs

Researching where rocks are found is necessary and interesting – don’t neglect to inspect old magazines and field guides from 40, 50, 60 years ago. You never know when a good location has simply fallen through the cracks and is waiting for you to find it and come explore! You’ll find that property ownership has changed over the years, however, don’t neglect to contact current property owners about that old information – many people are excited to find colorful rocks and minerals and are surprised they are underfoot.

“Looking down the wash where the good petrified wood is found. Floowaters that uprooted the tree in the foreground also uncovered new gem material.” – Photo by Eugene M. Beason.

So, when ever the rain is hard in colorado, new material is unearthed!

The Top Ten Mineral Localities on Earth (or, so we feel)

Philip M. Persson

3139 Larimer St., Denver, CO, 80205

perssonrareminerals.com

Graduate Student, Dept. of Geology & Geological Engineering

Colorado School of Mines

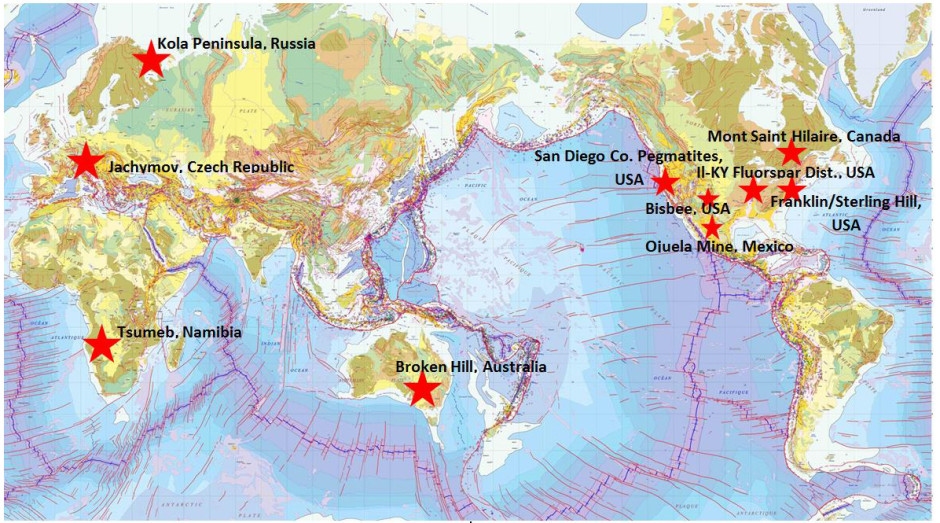

I have often had collectors ask me what localities I consider to be ‘important’ or ‘world-class’ as far as diversity, quality and quantity of minerals, and I’ve also spent much time pondering this question myself. In the end, the answer is highly subjective, depending on the person’s interests and experience in mineralogy and what drives them as collectors. There are ‘mineralogical rainforests’ such as Mont Saint Hilaire, Canada or Russia’s Kola Peninsula which, while not well-known for large aesthetic crystallized specimens, host an incredible diversity of mineral species- a seemingly infinite combination of a finite set of elements which attests to the unique geologic conditions under which they form. Then there are locales that have produced iconic and beautiful examples of one or perhaps a few minerals, but are otherwise fairly ‘simple.’ Colorado’s Sweet Home Mine or the Elmwood Mine in Tennessee likely fall into this category. In my opinion, the best localities are those that successfully bridge the gap between these extremes; those that have produced beautiful, highly collectible crystals but also have a deep appeal to the academic mineralogist or serious systematic collector. The following is a brief, somewhat arbitrary list of what I consider to be 10 of the top such locales, and I hope you enjoy my musings on each mineralogical treasure chest. –Phil Persson, Denver, Colorado December 2015

1.) Franklin & Sterling Hill, Sussex County, New Jersey, USA

Willemite & Franklinite crystals, Franklin Mine, 15 cm across (photo © kristalle.com, Tucson Show 2008)

Franklin. The name instantly kindles an affectionate smile or nod from seasoned rare species or fluorescent mineral collectors, and perhaps a begrudging acknowledgment from collectors of aesthetic minerals like gem crystals. No matter your interests, however, the unique appeal of Franklin (and it’s slightly smaller sister deposit, Sterling Hill) cannot be denied. These two mines, both now closed, are situated in the rather bucolic Northwest corner of the much-maligned state of New Jersey, approximately 45 airline miles from New York City. The unique and varied mineralogy of Franklin & Sterling Hill (over 350 mineral species now known, a number exceeded only by Mont Saint Hilaire and a German mine whose mineral endowment can be equally attributed to the forces of nature and the persistence of German micromounters) can be attributed to the unusual forces that led to their creation.

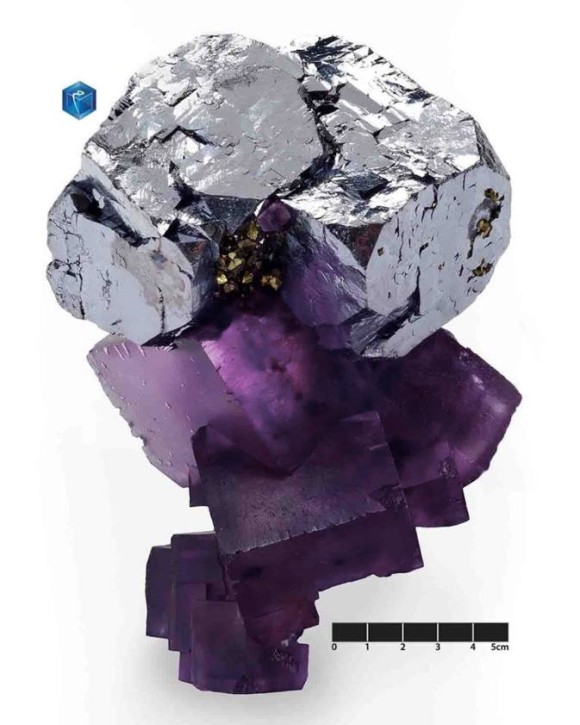

Passaic Open Pit with Sterling Hill Orebody under shortwave UV light at night (photo © Sterling Hill Mining Museum)

Originally thought to be seafloor volcanogenic massive sulfide deposits (previously termed ‘exhalites’), which formed near ‘black smoker’ type hydrothermal vents in a rifting environment in the late Proterozoic period, the Franklin & Sterling Hill orebodies were later subjected to fairly high-grade regional metamorphism (upper amphibolite facies) which turned the surrounding carbonate rocks into crystalline marbles, and transformed the fairly benign sulfide mineralogy of the proto-deposits into the exotic mixture it is today; defined principally by the Zn-Fe-Mn oxide Franklinite, the Zn-silicate Willemite, and the Zn-oxide Zincite. None of these minerals can be considered ‘common’ on a global scale, and two are essentially unknown outside the district. Metamorphism also introduced a suite of igneous intrusives of varying composition, from basaltic ‘camptonite’ dikes to felsic pegmatites with their own metasomatic reactions and accompanying fluids, which altered and further complicated the already diverse mineral assemblages present.

I will not delve too deeply into the history of the Franklin-Sterling Hill District, which could (and does) occupy an extensive treatise unto itself- suffice it to say that the orebodies, which originally outcropped in a fairly spectacular fashion, have been known since at least the late 17th century and probably earlier, but metallurgical issues arising from the complexity of the ores as well as disorganization of various mining entities prevented large-scale mining until the later part of the 19th century. From ~1880 to WWII was the ‘heyday’ of Franklin & Sterling Hill, with extensive scientific investigation of both deposits by many of the leading mineralogists of the day, such as Charles Palache & Clifford Frondel. Numerous new minerals to science were described, and the genesis of the deposits was fiercely debated. The combined output of the two mines, in total some ~40,000,000 tons of ore averaging >20% Zn (grades generally unheard of today) and substantial Fe & Mn propelled the owner, the New Jersey Zinc Company, into the upper leagues of the mining industry and allowed them to expand all over the U.S and the world (Dunn 1995). When the Sterling Mine finally brought its last ore bucket to the surface in early 1986, the district had a several hundred year history of mineral collecting and mineralogical science, as well as a robust ‘local scene’ with fierce competition for choice specimens and a club which fostered the community through mineral shows and other events.

It would take another monograph (this exists as well, authored by former-Smithsonian mineral guru Dr. Pete Dunn, and is a must-have for the serious Franklinophile) to describe the minerals of Franklin & Sterling Hill in detail, so I will just say a few words about some of the more notable species. At the top of the list of course are the ore minerals: franklinite, willemite, and zincite. With the exception of willemite (and this is debated amongst some), Franklin & Sterling Hill have produced by far the world’s premier crystallized examples of these species; in atypically-attractive euhedral crystals, up to 20 cm. on edge for Franklinite, and similarly large (or larger) for willemite. Willemite is a ‘chameleon’ at Franklin-Sterling Hill and occurs in nearly all imaginable colors and textures. Early 20th-century New Jersey Zinc Company chemist Lawson Bauer had a box of over 50 specimens (now in Harvard University’s collection) he would often have visitors try and identify. The trick is they were all willemite! Willemite even occurs rarely as flawless, gemmy prisms in attractive shades of green and yellow to blue to 4 or 5 cm. in size, which any real Franklin collector would murder their grandmother for. Zincite also occurs as sharp blood-red pyramids up to 5 cm, though 99% of it is massive.

Next in importance and distribution in collections are probably the Mn-bearing and so-called ‘skarn minerals’, Rhodonite being the most important. Broken Hill, Australia or Brazil have perhaps produced gemmier and more lustrous Rhodonites, but as far as sheer abundance, diversity and mineral associations, nowhere can beat Franklin. Attractive pink to red rectangular prisms to 20+ cm. embedded in white calcite matrix associated with willemite and franklinite crystals comprise the Franklin ‘uber-classic.’ The best ones have been painstakingly excavated from their enclosing calcite using small dental picks and hammers. Bustamite also occurs in excellent crystallized examples, as well as a host of much rarer Mn-bearing species such as Johannsenite, Hodgkinsonite, and Leucophoenicite (all having their type-locale at the Franklin mine). Species such as these illustrate that truly ‘world class’ localities exhibit the geochemical attribute of having a mineral representing essentially every thermodynamically-stable combination of a ‘signature’ set of elements. In the case of Franklin & Sterling Hill, these elements include Zn, Mn, Fe, Si, As, O, Ca, B, Pb, Ba, and a handful of others. None of these is particularly rare in the earth’s crust, but when combined in enough ways, new minerals to science which are globally-scarce are bound to result.

No discussion of Franklin would be complete without mentioning the fluorescent minerals. Mineral fluorescence, a spectacular property some minerals exhibit when certain outer shell (or ‘valence’) electrons are energized and emit vibrantly-colored visible light colors when excited by ultraviolet light sources, perhaps reaches its global zenith at Franklin. Over 80 minerals found at Franklin & Sterling Hill fluoresce under UV light, and many in bright and attractive combinations of color known the mineral world over. The cause for such a diversity of fluorescent minerals has been much debated, but probably involves the metamorphic and geochemically-complex nature of the deposits, as well as the abundance of certain elements such as Mn & Pb thought to act especially well as ‘activators’, or elements receptive to U.V light-induced excitation of key electrons. One of the major ore minerals at Franklin & Sterling Hill, willemite, fluoresces bright green under shortwave U.V light, and the major gangue mineral for both deposits, calcite, fluoresces bright red due to trace manganese, and together these minerals form a vivid fluorescent combination known locally as ‘red and green.’ This material has made its way into mineral collections around the globe, as have examples of minerals like hardystonite, esperite, margarosanite, clinohedrite, hydrozincite, sphalerite, roeblingite, and more. Some of these minerals, like roeblingite, margarosanite, and manganaxinite, are rare and restricted in their occurrence even at Franklin, and are highly-coveted by collectors even in modest examples. Others such as willemite, calcite and hydrozincite can still be easily collected today and are sure to delight any first-time visitor to the area.

Finally, the huge diversity of ‘rare’ species must be acknowledged. I put rare in quotation marks because it is a relative term at these enigmatic deposits, but some minerals are ‘truly rare’ and are unknown outside Franklin/Sterling Hill, or have global amounts totally a few grams of micro-crystals. It would be futile to describe these in detail here, but suffice it to say that they have names like Gerstmannite, Walkilldellite, Hauckite, Ogdensburgite, Kraisslite, Cahnite, Charlesite, and Samfowlerite which pay homage to their shared type locality and the scientists and collectors whose passion for the district led to their discovery. While the mines of Sterling Hill & Franklin have been closed since 1986 and 1954 respectively, their legacy is proudly carried on by two superb museums and a small army of local collectors and aficionados who almost without thinking refer to all rocks not from the area as ‘foreign.’

2.) Mont Saint Hilaire, Quebec, Canada

Serandites to 15 cm in the Royal Ontario Museum (photo © Dave K. Joyce)

First Franklin, now Mont Saint Hilaire!? Surely, the collectors of aesthetic and dare I say, “normal” minerals are now really rolling their eyes and assuming I must have some hidden ugly mineral agenda. But wait! Have you not seen the lustrous, bright orange 20 cm. Serandite crystals studded with lustrous white analcime golf balls? Or the lemon-yellow tablets of bright Catapleiite with swords of lustrous red maganeptunite shooting out of them? Or the brilliant-blue cubes of carletonite? Or perhaps the gemmy red crystals of Rhodochrosite on a bed of shiny natrolite prisms? Not everything at the ‘super classic’ pair of quarries nestled in an enigmatic hillside in the Quebec countryside requires a microscope to see. But, for those with an eye for the rare and unusual, Mont Saint Hilaire truly opens up another universe, with 400+ known mineral species and more awaiting proper documentation.

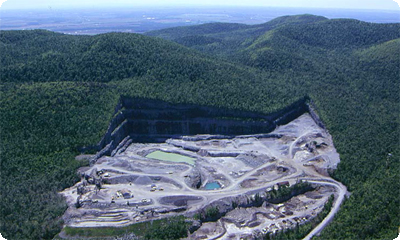

aerial photo of Poudrette Quarry ( photo © McGill University)