Clickbait-style lists have long circulated throughout the internet regarding the dangerous effects of a variety of mineral species – unfortunately these lists are often riddled with inaccuracies. We’re here to clear up some of that misinformation. Our primary list here will be minerals that are reported to be toxic because they contain toxic elements, but there will be some special mentions of other types of toxic risks at the end!

Disclaimer: our goal here is clear up some rampant fear-mongering, but any substance in significant doses or in specific situations can be very dangerous – even water can be deadly if consumed in significant quantities, and it will definitely kill you if you try to breathe too much of it! As a general rule, don’t eat your mineral specimens, don’t grind them into powders and snort them, don’t cook them and inhale their vapors, and please don’t look for any other ways to put them into your body. They just don’t belong there. Keep minerals out of reach of pets and children. And wash your hands – it’s just good hygiene anyway.

11. Fluorite

Fluorite from Rogerley Mine, Frosterley, Weardale, North Pennines, County Durham, England, UK – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Fluorite (CaF2) is a mineral that is listed as being dangerous because it contains the element fluorine, which by itself can be some nasty stuff. However, when fluorine is bonded with calcium, it has entirely different properties than fluorine by itself.

To better understand this, let’s take a little detour and talk about the mineral halite (NaCl – sodium chloride). Sodium (Na) is a highly reactive alkali metal that forms flammable hydrogen and caustic sodium hydroxide when it comes into contact with water – in short, it will burn you if it touches moisture on your skin, eyes, etc. Chlorine is a toxic gas that attacks the respiratory system, eyes, and skin. However, when deadly sodium bonds with toxic chlorine to form halite, we end up with table salt, a compound that we frequently add to food.

Similarly, fluorite does contain fluorine (which is some nasty stuff) but when fluorine is bonded with calcium, it has entirely different properties and does not inherently carry the risks of elemental fluorine.

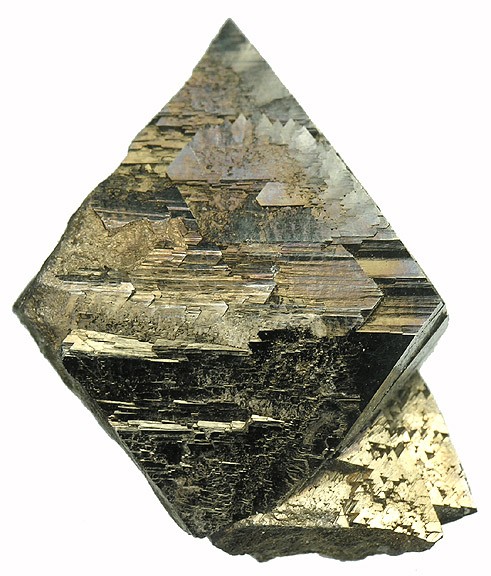

10. Pyrite

Pyrite from Huaron Mining District, San Jose de Huayllay District, Cerro de Pasco, Daniel Alcides Carrión Province, Pasco Department, Peru – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Pyrite (FeS2) is a relatively common mineral, often colloquially known as Fool’s Gold because of its brassy appearance. Pyrite is included on lists of toxic minerals because it might contain small amounts of arsenic.

Yes, pyrite can contain some arsenic, but since pyrite is not soluble in water or hydrochloric acid it poses no risks when handled.

An important thing to understand is that for any substance to be harmful, it must have bioavailability. Bioavailability is a term used to describe the degree and rate at which a substance is absorbed into a living system. A substance with high bioavailability can be readily absorbed into your body, whereas a substance with low bioavailability cannot be.

With many minerals, bioavailability will depend on the solubility of a mineral. Most material that has solidified (crystallized) has done so in a way that results in a stable, non-reactive substance. Minerals that aren’t stable tend to easily break down and often don’t survive very long. Solubility requires a fluid, and when considering potentially toxic minerals, the two most important fluids to consider are water (perspiration and saliva) and hydrochloric acid (stomach acid). Minerals that are soluble in water are a possible risk when handling the material, whereas minerals soluble in hydrochloric acid are a possible risk if the material is ingested.

9. Galena

Galena from Elmwood mine, Carthage, Central Tennessee Ba-F-Pb-Zn District, Smith County, Tennessee, USA – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Galena (PbS – lead sulfide) is often listed as a toxic mineral because of its lead content.

However, when lead is chemically bonded with sulfur, we find a highly insoluble compound – lead sulfide is virtually insoluble in water, and only very slightly soluble in hydrochloric acid.

While we’re here, let’s talk a little more about the toxicity of lead. It’s common knowledge that lead is toxic, but that is a concept that has come from the ban of lead oxide. Metal lead isn’t banned at all! There are many nuances to chemistry that we don’t have time to explain in depth in this article, but it is important to realize that an element in itself isn’t toxic – toxicity is complicated and is very specific to what kind of reactions can happen when any element at any given oxidation state interacts with anything else. One thing is pretty straightforward though: if a stable substance doesn’t dissolve, it has a low chance of being able to react with anything, thus it cannot create any change that might interact with the human body.

8. Stibnite

Stibnite from Wuning Mine (Wuling Mine; Qingjiang Mine), Qingjiang, Wuning County, Jiujiang Prefecture, Jiangxi Province, China – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Stibnite (Sb2S3 – antimony sulfide) is listed because of its antimony content, but again it is nearly insoluble and poses no risk.

For some technical talk, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) describes chemicals in terms of LD50, which is a number that measures the dose needed to kill 50% of individuals. This number is measured in the weight of chemical per unit weight of body tissue (usually this is in milligrams per kilogram or mg/kg).

The CDC lists studies of the LD50 of elemental antimony in rats being between 900 and 20,000 mg/kg, which roughly translates to 90 to 2,000 grams (~0.2 to over 4 pounds) of antimony in a 220 pound human (though please note that different animals can have different sensitivities to a substance). Long story short, it would likely be difficult for a human to ingest that much stibnite to begin with, and, with a very low solubility, it is unlikely it would remain in your system long enough to release enough native antimony to cause any ill effects.

7. Hydroxylapatite

Hydroxylapatite from Sapo mine, Conselheiro Pena, Doce valley, Minas Gerais, Southeast Region, Brazil – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH) – calcium hydroxide phosphate) is mentioned on lists of toxic minerals because it is the same material as bone and, supposedly, if you ingest it, it will cause blockages by depositing bone in your arteries.

This is just utter hogwash. Hydroxyapaite, also called hydroxylapatite or apatite-(CaOH), is soluble in hydrochloric acid but will break down into calcium ions and phosphoric acid, both of which exist in your body naturally. (Fun fact: phosphoric acid is the ingredient in some sodas that give it a tangy taste.) If you were to ingest large amounts of hydroxyapatite, you may find yourself with a case of kidney stones, but to fear your arteries turning into bone is completely unnecessary.

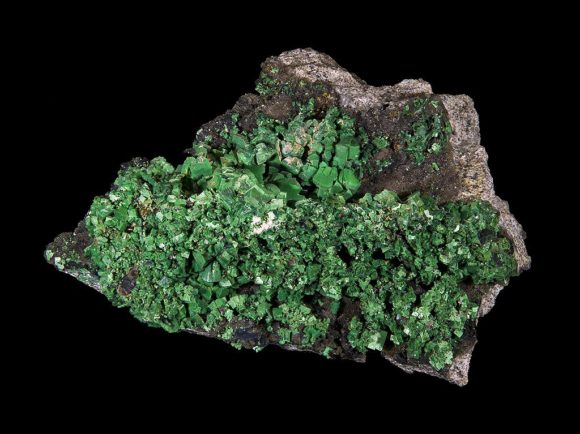

6. Coloradoite

Coloradoite from Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Kalgoorlie-Boulder Shire, Western Australia, Australia – photography from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Coloradoite (HgTe – mercury telluride) makes the list for containing both mercury and tellurium.

This compound is not soluble in water or hydrochloric acid and poses no risks to handling. It’s also a particularly rare mineral that you’re not likely to happen across accidentally.

There is another risk we should discuss though – mineral dusts. When looking at solubility and resulting bioavailability of minerals, the first concern is the introduction of large quantities of the material into the body (i.e. ingesting 4 pounds of stibnite). However, there is a more innocuous way for minerals to enter your body and that is through your lungs. Since the lungs do not flush themselves out as regularly as the digestive tract, minerals can be trapped in the body for longer periods of time which gives them more time to dissolve. Dusts also have more surface area that larger chunks of material, which allows chemical reactions to occur more easily. These things coupled together mean that material inhaled into the lungs could dissolve over time and cause serious health concerns. (See more about risks related to inhalation below in our special mentions.) Do NOT breathe your minerals!

5. Hutchinsonite

Hutchinsonite from Quiruvilca Mine (La Libertad Mine; ASARCO Mine), Quiruvilca District, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Peru – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Hutchinsonite (TlPbAs5S9 – a lead/thallium-bearing sulfoarsenide) appears on lists for containing both lead and thallium.

Again, hutchinsonite is a mineral with very low bioavailability, since sulfoarsenides and sulfoantimonides are relatively insoluble.

Other thallium minerals with a higher solubility may certainly pose a risk for thallium poisoning (we seriously don’t recommend anyone try this being poisoned by this, it’s pretty awful), but hutchinsonite is not the thallium mineral to be afraid of.

4. Cinnabar

Cinnabar from Wanshan Mine, Wanshan District, Tongren Prefecture, Guizhou Province, China – photograph from Parent Géry.

Cinnabar (HgS – mercury sulfide) is another mineral that is regarded as a toxic mineral because it contains an element regarded to be dangerous by itself – mercury.

However, like galena, the elements in cinnabar are bonded together – inorganic mercury sulfide is virtually insoluble.

Another risk we should discuss is reactions instigated by heat. Like many minerals, cinnabar can decompose thermally, meaning that if you were to cook it at a sufficiently high heat, it will break down and may release toxic vapors. Grinding these minerals can also cause similar risks, likely because of local heating caused by friction. Do not heat your minerals, as heat may cause reactions with dangerous byproducts! However, this does mean that it is harmful to physically handle a specimen of cinnabar. Do NOT cook your minerals and absolutely do NOT inhale their vapors!

3. Orpiment

Orpiment from El’brusskiy (Elbrusskii) Arsenic mine, Elbrus, Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, Northern Caucasus Region, Russia – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Orpiment (As2S3) and its cousin realgar (As4S4) are cited as being even more dangerous than arsenic because of the associated sulfur.

We call hogwash on that because when arsenic is chemically bonded with sulfur, it is far less soluble than native arsenic.

Orpiment is slightly soluble in water (i.e. saliva and perspiration), so it should be handled with care, but it is not necessary to be terrified of this mineral. Wash your hands after handling it, and consider using gloves to avoid skin contact.

Realgar, on the other hand, is not soluble. However, with exposure to sunlight, realgar can alter to pararealgar, which forms a dusty coating coating and can be dangerous if inhaled.

2. Arsenopyrite

Arsenopyrite from Yaogangxian Mine, Yizhang County, Chenzhou Prefecture, Hunan Province, China – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Arsenopyrite (FeAsS), like pyrite, receives its terror because of its arsenic content.

This time, there is most certainly arsenic in the chemical composition, but like pyrite, arsenopyrite is not soluble in fluids related to the human body and is not dangerous.

However, we’ve included this higher on the list because here is another factor to be very cautious with. There are rumors of arsenopyrite with a white coating that turned out to be a soluble arsenate, which would be very toxic! Minerals can react with other factors in the environment before and after they come into your possession – if your mineral has a crust, coating, powder, or other substance associated with it, that may be an indication that some chemical reaction has occurred. If you find an unknown substance, do not put it into your body!

1. Chalcanthite

Chalcanthite from Planet Mine, Planet Mine group, Planet, Santa Maria District, Buckskin Mts, La Paz Co., Arizona, USA – photograph from Parent Géry.

Chalcanthite (CuSO4 · 5H2O – a hydrated copper sulfate) is one of the few minerals that appears on these lists that is definitely worth some concern – this one could actually kill you.

This mineral is very soluble in both water and hydrochloric acid, which readily releases copper that can then be absorbed by the body and, in large enough quantities, could cause copper poisoning. The good news is that one of symptoms of ingesting chalcanthite is vomiting – one of the first things your body does with chalcanthite is try to spit it right back out. The bad news is that the LD50 for chalcanthite is 30 mg/kg in rats, so roughly 3 grams or 0.1 ounces) in a 220 pound human. It is recommended that you seek medical attention if you ingest chalcanthite, but the easiest method to avoid copper poisioning from chalcanthite? Do not let it get into your body!

We hope this has cleared up some of the common misconceptions about mineral toxicity – the important take away is that the toxicity of a mineral has everything to do with how it’s handled. You do not need to fear minerals. If you practice common sense and take proper precautions, every mineral is absolutely safe! Stay smart, stay educated, and live on to enjoy the beauty of these natural works of art.

(This is technically the end of this article, but for any of you with a burning curiosity to learn more, we’ve included some special mentions below!)

Special Mentions: Inhalation!

A number of minerals have been listed as toxic for risks associated with inhalation of fine particles. The following minerals carry a risk that is quite a bit different from solubility, as the concern is not one of chemical reactions, but of physical damage created by fine particles.

It is important to realize that inhalation of any particulates is not healthy (smoke, air pollution, etc.), and this is no reflection on the danger of a single mineral in particular. If you are handling minerals in a situation where you are creating mineral dusts (lapidary work, for example), it is recommended that you wear a dust mask, or use a liquid component such as water or oil to keep the dust created by grinding from spreading in the air. These precautions are a good practice regardless of what material is being worked. Dust can also be a concern for those who work in mining or collect minerals themselves in the field – again, if you are working in a dusty environment, protect yourself and your lungs by using a dust mask or respirator.

Asbestos

Riebeckite from Prieska, Pixley ka Seme District, Northern Cape, South Africa – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Asbestos itself is not a single mineral, but a name used to describe a number of minerals when they occur in a fine, fibrous form (crocidolite, chrysotile, tremolite, riebeckite, and actinolite are just a few examples).

The danger of asbestiform minerals comes only when particles of them are inhaled – don’t inhale these specimens and you are at no risk.

Erionite

Erionite from Phelps Dodge Corporation Well No. 1, Little Ajo Mountains, Ajo District, Pima County, Arizona, USA – photograph from Matteo Chinellato.

Erionite, another “mineral” that is actually a group of minerals, appears on lists because of its fibrous nature, which reportedly can result in mesothelioma.

Like any other mineral, don’t inhale it! Further, erionite is an uncommon mineral that most people are unlikely to ever encounter.

Quartz

Quartz from East Coleman Mine (Ron Coleman Mine; Old Coleman Mine; West Chance; Dierks No. 4; Blocker Lead; Geomex), Jessieville, Garland County, Arkansas, USA – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Quartz (SiO2 – silicon dioxide), like asbestos, shows up on a few lists due to risks related to inhalation.

Inhalation of quartz dust can cause a disease caused silicosis – however, quartz itself is remarkably durable (unlike asbestiform minerals) and most people are not likely find themselves in a situation where quartz dust is any risk. Handling a quartz crystal itself will not cause any damage (unless perhaps someone chooses to hit you with it), but use caution when cutting and polishing quartz, or when collecting minerals in a dust-heavy environment.

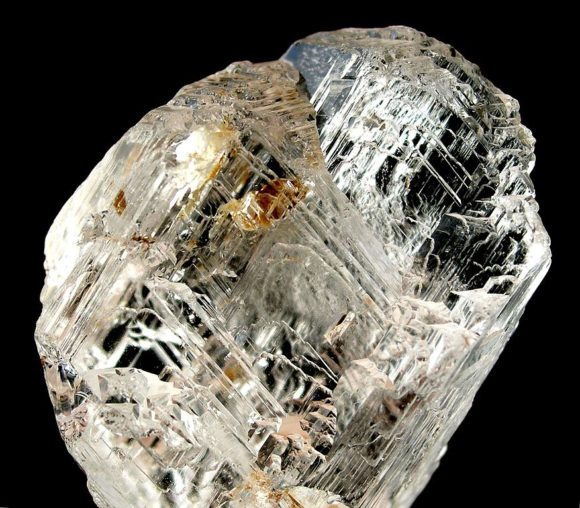

Phenakite

Phenakite from Jos Plateau, Plateau State, Nigeria – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Phenakite (Be2SiO4 – a beryllium silicate) is mentioned on lists for its toxic beryllium content.

Silicates are notoriously insoluble, and phenakite is no exception. However, many beryllium minerals are often cut and polished into jewelry, and those engaging in lapidary work should be cautious of inhaling the dust from these minerals.

Special Mentions: Radioactive Minerals!

Torbernite

Torbernite from Margabal Mine, Entraygues-sur-Truyère, Aveyron, Midi-Pyrénées, France – photograph from Didier Descouens.

Torbernite (Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2 · 12H2O) makes the list for its uranium content.

Radioactivity is a very complex subject we really don’t have time to delve into here, but if you’re interested in that topic, send us a message to let us know and we’ll look at addressing it in another article! For now, we’ll issue the standard caution: don’t eat them, wash your hand after handling them, and store them in an area with good ventilation and away from your regular daily activities.

K-Feldspar

Microcline (var. Amazonite) from Konso, Sidamo-Borana Province, Ethiopia – photograph from Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com.

Potassium feldspar, or K-feldspar, is a term that refers to potassium dominant feldspars, and are included on lists because they are radioactive.

We still aren’t going to get into radioactivity in this article, but we will mention a few fun facts here:

First: potassium is well known for its radioactive isotope often referred to as K40. However, potassium feldspars are no more radioactive than a banana, which also contains potassium!

Second: potassium feldspars are one of the most abundant groups of minerals on earth.

Third: here’s a mind-blowing spoiler to leave you with: the EARTH is radioactive! That radioactivity is one of the key sources of heat on our planet and part of the reason our planet is habitable.

Recommended for Further Reading:

Clyde Spencer – Mineral Toxicity

John Betts – Water Soluble Minerals

marulla.com – Mineral Solubility

A special thanks to Yoshihiro Kobayashi for his insights into many aspects of chemistry.